‘I am a woman, not an exhibit.’ The effects of the male gaze in art, literature and today’s society

Journalist Naomi Frisby on Elizabeth Macneal's exploration of the male gaze in The Doll Factory and the parallels that can be drawn with today’s society.

Elizabeth Macneal’s The Doll Factory is an intoxicating story of love, art, obsession, and one woman’s struggle for freedom and agency in Victorian London. Throughout this enthralling debut, Elizabeth brings the prevalence and ramifications of the male gaze into the spotlight. Here, journalist Naomi Frisby explores the parallels that can be drawn with today’s society, and the implications this has for us all.

‘I am a woman, not an exhibit.’ – Iris Whittle

In 1975, film critic Laura Mulvey coined the term ‘the male gaze’. It refers to the presentation of women in visual arts and literature from a male, heterosexual perspective where women are depicted as sexual objects for the pleasure of the male viewer. Men have agency; women are passive and dehumanised.

The first time ‘Starey’ Silas Reed and Louis Frost, the central male characters in The Doll Factory, encounter the novel’s protagonist, Iris Whittle, the emphasis is on them looking at her. Silas, the proprietor of a shop of curiosities, notices Iris on the way to The Great Exhibition. He sees her height, her red hair, her womanliness. Iris reminds him of Flick, his childhood friend, and this alone is enough for him to believe that he and Iris have a connection, ‘an invisible cord which united them’.

Louis, a fictional member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, is out in London with Dante Gabriel Rosetti and John Everett Millais looking for ‘stunners’, the term the PRB assigned to the women who became their models. When Louis complains he cannot find anyone for his latest painting, The Imprisonment of Gugimar’s Queen, Silas, desperate to ingratiate himself with these men, tells them about Iris. They visit the shop where Iris is employed to paint dolls and stare at her through the window.

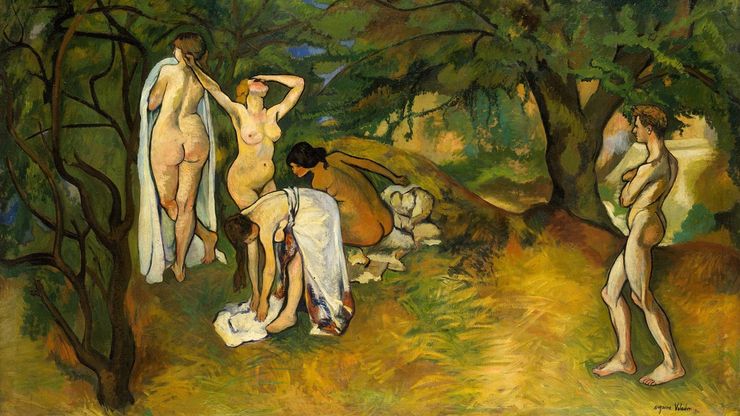

By linking Silas and Louis, Elizabeth Macneal makes a direct correlation between the male gaze in art and the male gaze in society. The legacy of the PRB is one of red-haired, pale-skinned, long-necked women posed as courtly lovers in ancient, medieval or Shakespearian tales. The women connected to the movement are remembered as models, despite several of them – including Elizabeth Siddal – being painters in their own right. Laura Mulvey also made this connection. She described the male gaze as a social construct, emphasising that if women are seen as objects to be valued for their beauty, physique and sex appeal in art, they will also be seen as such in life.

The male gaze and the idea that men are entitled to women’s bodies remain threaded throughout society. Only 30% of the art housed in the Tate group of galleries is by women. Female characters made up just 35% of speaking roles in the highest grossing films of 2018 - none of which had a female director. Women are more likely to read an equal number of books by male and female writers, while men predominantly read books by other men. As long as female artists aren’t considered equal to male artists, aren’t allowed to take up an equal amount of space, aren’t heard, women will continue to be viewed through the eyes of men who’ve fashioned them via their desires. This has serious repercussions: from street harassment - in the form of comments, gestures, whistling, following and touching - to assault and rape, men take their cues from the portrayal of women in art and literature.

Silas’ obsession with Iris builds throughout The Doll Factory. Through his watching, he creates an idealised picture of a woman who will meet his every whim. His Iris responds with adoration. In reality, she barely remembers him.

Macneal chooses an alternate route for Louis. When he approaches her to be his model, Iris is unimpressed with his insistence that ‘You must be my Queen’, wanting more than to be immortalised and admired. As the novel progresses, Louis begins to see Iris in a different way; his understanding of her as a person changes the focus of his painting and his idea of love.

But the real triumph of The Doll Factory is Iris. The story begins with her painting a self-portrait in secret, the act of which provides her with a sense of control over her own body. When she agrees to model for Louis, she insists she will only do so if Louis teaches her to paint. Iris has agency which she refuses to relinquish. She is ambitious and ‘will not be afraid to take up space’.

There is hope in current society too. Social media movements such as #EverydaySexism and #MeToo have amplified women’s voices about the effects of the male gaze, while #AskHerMore and #ReadWomen highlighted women’s contributions to visual arts and literature.

This year, the women associated with the PRB will finally have their agency recognised too. The work of twelve artists, including Elizabeth Siddal, Joanne Wells and Marie Spartali Stillman, is to be exhibited at the National Portrait Gallery under the title Pre-Raphaelite Sisters. They will take up space and begin to shift the emphasis from being admired for their looks to being credited for their talent. Iris’ words could act as the exhibition’s subtitle: ‘I’m not a piece of canvas - I’m a real woman.’

In this interview Elizabeth Macneal discusses her inspiration for The Doll Factory and the women of the pre-Raphaelite movement:

In this episode of Book Break, Emma tells us more about Silas's dangerous obsession in The Doll Factory, and recommends more books about obsession.

The Doll Factory

by Elizabeth Macneal

In London, 1850, against the backdrop of the Great Exhibition, Iris meets two men who will change her life forever. Her introduction to pre-Raphaelite artist Louis introduces her to a world of art and love, while a chance meeting with Silas, a collector of the strange and beautiful, triggers a dangerous obsession . . .