10 weird facts about the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

Here's everything you need to know about the group of real-life artists, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, who inspired Elizabeth Macneal's novel The Doll Factory, now a major TV series available on Paramount+.

Set in 1850s London, Elizabeth Macneal’s intoxicating novel The Doll Factory has just been adapted for television and is available to watch on Paramount+. The story follows Iris Whittle, a young woman who aspires to be an artist, as she embarks on a thrilling new life in search of freedom. After a chance meeting, Iris agrees to model for one of the Pre-Raphaelite painters, Louis Frost, in exchange for him teaching her to paint. Her horizons begin to expand, as she is thrown into the bohemian world of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. The Brotherhood was a real-life group of radical young artists, including Dante Gabriel Rossetti, which was founded in London in 1848 and who sought to challenge the artistic ideals of their time.

From a fondness for wombats to attracting the ire of Charles Dickens, Elizabeth shares ten interesting facts about the brotherhood which first inspired the novel.

If you're looking for more inspiration, discover our edit of the very best historical fiction books, or read journalist Naomi Frisby's take on The Doll Factory and the effects of the male gaze.

1.The Brotherhood was originally a secret society

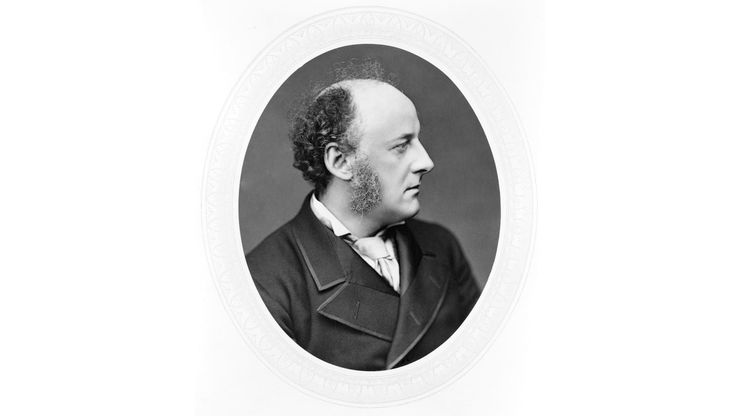

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was founded by John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt and Dante Gabriel Rossetti in 1848, and expanded to four further members. They believed that contemporary art had become corrupted and commonplace, and they wanted to return to the vivid colours, detailed compositions and realism of the Medieval period.

At the beginning, they remained a secret society, and signed their paintings ‘PRB’, refusing to explain what the initials meant. Some, like my character Silas, guessed it stood for ‘Please Ring Bell.’ Others had wilder theories, such as ‘Penis Rather Better.’

While Rossetti, Millais and Holman Hunt all feature in The Doll Factory, Louis Frost is entirely fictional.

2. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was known to ‘trawl’ the streets for stunners

Ever since I first saw the paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites, I was struck by the powerful and haunting beauty of the female models and muses. The male artists were known to link arms on the streets and filter women past them, seizing on potential models whom they deemed ‘stunners.’ Janey Morris was spotted at a theatre in Oxford, Fanny Cornforth on the streets. The most significant inspiration to me was Lizzie Siddal, a cutlery-maker’s daughter who worked in a milliner’s shop. She was spotted by Walter Deverell (who was on the periphery of the PRB) and his mother when they were shopping for a bonnet. She had always enjoyed painting, and sketched on butter wrappings as a child. She left her job in the milliner’s shop, and threw herself into the decadent and vivid world of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, where she had a love affair with Rossetti, became an artist in her own right (with some tuition from Rossetti), and posed for many famous Pre-Raphaelite paintings, such as Ophelia. I based the trajectory of my fictional character, Iris, on the early career of Lizzie – she is noticed by the artists when working in a doll-making shop.

3. Rossetti exhumed Lizzie Siddal to retrieve a book of poetry he had buried with her

In the early days of their relationship, Gabriel Rossetti was obsessed with Lizzie Siddal. This infatuation inspired his sister, Christina, to write the poem ‘In an Artist’s Studio’: One face looks out from all his canvases, One selfsame figure sits or walks or leans: We found her hidden just behind those screens, That mirror gave back all her loveliness. A queen in opal or in ruby dress, A nameless girl in freshest summer-greens, A saint, an angel — every canvas means The same one meaning, neither more or less. He feeds upon her face by day and night, And she with true kind eyes looks back on him, Fair as the moon and joyful as the light: Not wan with waiting, not with sorrow dim; Not as she is, but was when hope shone bright; Not as she is, but as she fills his dream. However, the relationship between Lizzie Siddal and Rossetti was far from straightforward, with Rossetti forming intense attachments to other women. Lizzie Siddal grew depressed, became addicted to laudanum (which was a drink of dissolved opium thought to have medicinal benefits), and her health suffered. Rossetti only agreed to marry her when it was thought she was dying. Two years later, she was found dead from a laudanum overdose, which was suspected to be suicide. As a gesture of his grief and love for her, Rossetti decided to bury the only manuscript of his poems with her. However, seven years later, he realised he had forgotten the poems and needed the income. A connection with the Home Secretary meant that permission was granted to have her exhumed without contacting her family. This took place after dark, with Rossetti’s agent in attendance. A rumour circulated that Lizzie’s features was perfectly preserved, and her coppery hair had continued to grow and fill the coffin. However, the truth of her decay was touched on by Rossetti who lamented the ‘great worm-hole right through every page’ of his Poems which were published in 1870.

4. Lizzie Siddal nearly died when Millais painted her in Ophelia

The story behind Millais’s painting of Lizzie Siddal in Ophelia wasn’t as calm and dream-like as the painting indicates, which I allude to briefly in the scene where Lizzie and Iris are eating dinner at Millais’s house. John Millais painted Lizzie Siddal lying in a bathtub, fully dressed. The bathwater was warmed by oil lamps placed underneath the tub. However, these extinguished themselves, and Millais was too engrossed in his work to notice, and Lizzie said nothing about it. As a result, she contracted a severe cold, nearly died, and her father chased Millais to cover her £50 doctor’s bill. Millais painted the bucolic setting on the banks of the Hogsmill River in Surrey, where he sat for up to eleven hours a day, six days a week, for five months in 1851. He wrote, ‘The flies of Surrey are more muscular, and have a still greater propensity for probing human flesh,’ and he was sued by a farmer for trespassing in a field and destroying the hay. Ophelia was displayed in the Royal Academy in 1852 and sold for 300 guineas.

Ophelia on Tate Britain Instagram

Ophelia by John Millais is on display at Tate Britain.

5. The Pre-Raphaelites were wombat-mad

The wombat Guinevere was inspired by the Pre-Raphaelites’ fascination with wombats. Later in life, Rossetti annoyed his neighbours in Cheyne Walk (including Thomas Carlyle, who complained about the noise), by owning a sickly menagerie. It consisted of exotic animals like raccoons, kangaroos, marmots and wombats. He trained a toucan (which he dressed in a cowboy hat) to ride on the back of a llama. The PRB were particularly enamoured with wombats. These animals found their way into their art and poems. The woodcut on the cover of Christina Rossetti’s Goblin Market features a wombat, and her poem included the line: ‘One like a wombat prowled obtuse and furry.’ She even coined the Italian word for wombat, ‘uommibatto.’ Rossetti owned two wombats, one of which was named ‘Tops’ after his friend William Morris (with whose wife, Janey Morris, he is suspected to have had an affair). He brought the creature to dinner where it slept in the large silver épergne. The wombat was sickly from its arrival, and soon died; Rossetti had it stuffed and placed in his hall. Rumours later circulated that Tops died because it ate a box of cigars, but this was allegedly untrue. However, I couldn’t resist giving Guinevere’s departed companion Lancelot the same cause of death.

6. Dickens hated the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

I loved exploring how a young and ambitious group of painters battled opposition in their quest to be recognised and taken seriously. The PRB had many critics, and some saw them as precocious upstarts, lacking the rigour of established artists, their realism tasteless. Punch published a balloon-headed parody of Millais’s Mariana, some attended The Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition merely to laugh at this painting, and critics wrote numerous contemptuous reviews (one of which I include word-for-word in The Doll Factory). Dickens was amongst those who loathed their art, and he launched this attack on Millais’s painting Christ in the House of his Parents: ‘You behold the interior of a carpenter’s shop. In the foreground of that carpenter’s shop is a hideous, wry-necked, blubbering, red-headed boy, in a bed-gown, who appears to have received a poke in the hand, from the stick of another boy with whom he has been playing in an adjacent gutter, and to be holding it up for the contemplation of a kneeling woman, so horrible in her ugliness, that (supposing it were possible for any human creature to exist for a moment with that dislocated throat) she would stand out from the rest of the company as a Monster, in the vilest cabaret in France, or the lowest ginshop in England. Wherever it is possible to express ugliness of feature, limb, or attitude, you have it expressed.’ I find it interesting that Dickens also critiqued the ‘ugliness’ of the model behind the painting as well as Millais’s craftsmanship.

7. Millais’s wife, Effie, was first married to Ruskin

In their early days, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood were huge admirers of John Ruskin. His letter to the Times (which I include in The Doll Factory) was a real turning point for them, and some respite from the critique they received. As Millais enthuses in The Doll Factory, Ruskin also offered to purchase Millais’s painting The Return of the Dove to the Ark, which was displayed in the 1851 Royal Academy. But while all of this was happening, Ruskin was in a neglectful and sexless marriage to Effie (née Gray), who was ten years his junior. It is not known why they never consummated their marriage. Ruskin later said that ‘her person was not formed to excite passion’ and that he was ‘disgusted with [her] person,’ which led some to conclude that she might have been menstruating on their wedding night, or that he was so used to the smooth forms of classical sculpture that he did not know that women had pubic hair. In 1853, Ruskin invited Millais to join him and Effie on a holiday to the Trossachs. Effie and Millais fell in love, and Effie told him about her unhappiness with Ruskin. There, Millais painted Ruskin in what Millais later described as the ‘most hateful task I have ever had to perform.’ Back in London, six years after marrying Ruskin, Effie had the marriage annulled due to non-consummation, too much scandal, and she went on to marry Millais and have eight children with him.

8. Rossetti was obsessed with redheads

Elizabeth Gaskell described her friendship with Dante Gabriel Rossetti (who was originally named Gabriel Dante Rossetti, but switched the order of his names to increase his connection with the great Italian poet): ‘I had a good deal of talk with him, always excepting the times when ladies with beautiful hair came in . . . It did not signify what we were talking about or how agreeable I was; if a particular kind of reddish brown, crepe wavy hair came in, he was away in a moment struggling for an introduction to the owner of said head of hair. He is not as mad as a March hare, but hair-mad.’

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Roman de la Rose 1864, Tate Collection

9. Millais was dangled from the window by his stockings

John Everett Millais was a child prodigy. His talents were so remarkable that his mother decided to move the family to London so that he could access better tuition and art schooling. At the age of eleven, he was the youngest ever student to be admitted to the Royal Academy. This incited the jealousy of others, and they called him ‘The Child’. His fellow students once left him hanging from a window by a pair of stockings, and he had to be rescued by a passerby.

10. William Morris was so disgusted by the Great Exhibition that he was physically sick

William Morris wasn’t associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood until after The Doll Factory is set, and he was never an official member.

However, he shared the PRB’s distaste for The Great Exhibition, and according to Liza Picard in Victorian London, ‘He so deeply, viscerally, deplored the examples of modern taste on view there that he had to leave, and be sick outside.’

The Doll Factory

by Elizabeth Macneal

London. 1850. On a crowded street, the dollmaker Iris Whittle meets the artist Louis Frost. Louis is a painter who is desperate for Iris to be his model. Iris agrees, on the condition that he teaches her to paint. Dreaming of freedom, Iris throws herself into a new life of art and love, unaware that she has caught the eye of a second man. Silas Reed is a curiosity collector, enchanted by the strange and beautiful. After seeing Iris at the site of the Great Exhibition he finds he cannot forget her. As Iris's world expands, Silas's obsession grows. And it is only a matter of time before they meet again . . .