Edward Platt

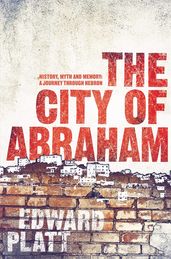

Edward Platt was born in 1968 and lives in London. His first book, Leadville, won a Somerset Maugham Award and the John Llewellyn Rhys Prize. He is also the author of The Great Flood which explores the way floods have shaped the physical landscape of Britain, and The City of Abraham, a journey through Hebron, the only place in the West Bank where Palestinians and Israelis lived side by side.