Being an immigrant writer in America today

Carmen Bugan, author of Burying the Typewriter, on why America needs the stories of its immigrants now more than ever.

Carmen Bugan, author of Burying the Typewriter,on why America needs the stories of its immigrants now more than ever.

The current political climate in the United States fills many people with anxiety, but it horrifies me. I am an immigrant and I feel that my values are directly under attack.

I come from a family of political dissidents. My father spent twelve years in Romania's worst prisons because he fought for the truth, human rights and freedom of speech. He bought a typewriter illegally; ordinary people were not permitted to own them, both typewriter and owner had to be fingerprinted and surveilled by police.

Dad buried the typewriter in the backyard every time he and my mother were finished with typing stacks of anti-communist manifestoes. We immigrated to the United States at the end of 1989 as political refugees, just when the Berlin Wall was brought down and the Romanian Revolution littered the streets of Bucharest with dead people who hoped for freedom.

My first poems were written to a photograph of my father which we kept in our beloved house, where we had been subjected to years of secret police surveillance while he served in prison. It took me time to understand myself as a freed person, to translate my poetry into English, and then write directly in English, which has become my adoptive, comforting language.

I left my native language because it felt corrupt by the informers who destroyed my childhood, by the surveillance which has turned my family and me into fearful and suspicious people, by the slogans thrown at us by a dictator who saw himself as the father of all people and tortured anyone who criticized him.

The English language was a rebirth: of speech after long silence, of dreams after despair, of hope and gratitude that my father's fight for freedom was welcomed and respected by Americans who gave us a home among them. My writing took roots in this beautiful new language and I could finally articulate my story and dream my place among my fellow Americans: I had become a naturalized citizen and also a linguistic citizen.

Out of gratitude for this country, immigrants may not say much to criticize it, but we are very sensitive to demagoguery and any gestures that threaten freedom of expression. We know all about grand, empty promises, policing the speech, the way a slogan can enter the heart of a family that struggles to pay bills.

We know how people can fall into the trap of words. We know when the rhetoric is directed against us. But those of us who are writers are aware of the price paid in our own families for the freedom to shout out ‘This is wrong!' and be heard.

Horrible stories about immigrants are commonplace, as is talk of deporting hard-working families and creating new rules about the ways in which people protest against injustice. All the while our new government are promising to make this country great again. This is a police state in the making and the worst part of it is that people are already afraid to stop it. I watch the major TV news channels in horror.

Why should this new vision of America determine how I am going to raise my own children? Why should I go to sleep at night worrying about the destruction of our health care and education systems, that our leaders are making enemies all over the planet, and shutting all Americans inside a big fat wall?

This is an open letter to the immigrant writers of the United States of America. Let us get to our notebooks and write the compassionate, amazing stories of immigrants who have made this country the reason the world still wants to flock here.

Let us write shimmering, nuanced, beautiful words, poems and stories full of love, let us show the Americans who welcomed us here the generosity of their hearts. Let us help those who cannot yet see the dangerous path America is taking, step away from it. Let the great American writers who have enjoyed working and growing in one of the most beautiful languages on earth, a language of song and poetry, let them join us with their stories of how we became their friends and learned from them.

I believe that the English language is hurting: it suffers from materialism, from empty slogans, and it has been reduced to buzzwords. We need to open our hearts to this language and in turn the language will give us the resources to resist lies.

The immigrant writers bring to the English language the wonder of looking at it afresh, and with gratitude. This is the wonder that most natives lose soon after that magic period in childhood when they begin to read and write, to unlock the power of words and the thrill that the language has opened to them the right of ways. This language needs words from other countries, rhythms from other parts of the world, tears and laughter from the huts and homes of people in faraway places; it must taste their fragrant foods and it must nurture their hopes.

We must not be afraid to look into the eyes of danger: let the writers be like surgeons who have enough emotional distance that they can perform that operation which removes the tumor.

There are many people who are discontent in this country. The writers must serve these people with good words that will bring peace and understanding. There is no love but in the word of it.

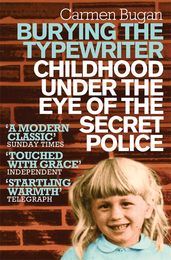

Burying the Typewriter

by Carmen Bugan

Subtitled Childhood Under the Eye of the Secret Police, this is a first-hand account of Romanian oppression, and a deeply personal child’s eye view of a father’s rebellion, arrest and imprisonment. At 2 a.m. on 10 March 1983, Carmen Bugan’s father left the family home, alone. That afternoon, Carmen returned from school to find secret police in her living room. Her father’s protest against the regime had changed her life for ever. This is her story.