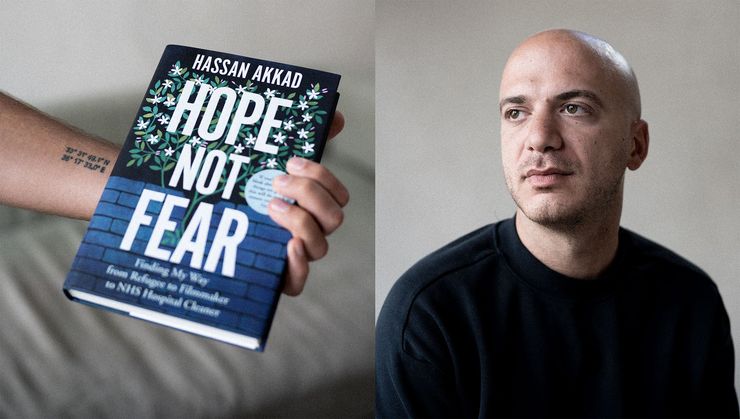

Syrian refugee, Hassan Akkad, on the triumph of hope over fear

Discover how Hassan Akkad overcame his rising fear and did everything he could to help when the coronavirus pandemic swept into his home city of London.

Hassan Akkad was a high school English teacher when war broke out in Damascus. As protests against the Syrian government filled the streets, Hassan took part and filmed the rallies. He was detained twice for a total of four weeks – an ordeal that involved torture and solitary confinement. After being released, he was banned from working and lost his teaching job.

In 2015, at the age of 32, Hassan reluctantly fled Syria and began a punishing eighty-seven-day journey across Europe via Turkey and the Calais Jungle. After arriving in the UK and claiming asylum, he returned to filmmaking and was part of the team that created the astonishing documentary Exodus: Our Journey to Europe, which won a BAFTA in 2017.

But when the pandemic struck in 2020, Hassan felt compelled to help in any way he could.

Here, Hassan tells us about the moment when he decided to enter a Covid ward as a hospital cleaner, joining a band of fellow immigrants that supported the NHS in its hour of greatest need. Hassan went on to document the intensity of the experience that followed, advocating for his fellow workers, winning them vital legal rights and gaining acclaim for his message of love and hope over fear and division.

I’ve changed a lot in the last ten years, but one thing has stayed constant. No matter what kind of danger I find myself confronting, I become overcome with an overwhelming desire to contribute as best as I can. To help. I don’t know exactly where it comes from. But my first instinct is to question what I can do to try and make things better. To ask how I can personally contribute. That’s how it was in March, when Italy became the new centre of the coronavirus. I watched news reports of people sitting on their balconies, playing musical instruments and singing to one another.

By then I was certain that the virus was coming to my adopted city of London and that it was going to cause untold heartache. I recognized the feeling of previous certainties shifting under my feet. But I also knew the best remedy for coping. I understood that there would definitely be ways to help. There always are. And in my experience, sometimes being there for others is the only way we have of taking control over difficult things. That’s why on 27 March 2020, sitting on my sofa in my flat in East London, I googled a simple question. ‘How can I help the NHS?’ Like everyone, I knew the health service was under great strain, that it might struggle to cope with the influx of coronavirus cases. An agency link popped up with a job listing for cleaners and porters. Next to the word ‘cleaners’ was another in brackets. Urgent. I looked at the documentation required. It asked for a DBS check and a passport. I had already applied for the former for a previous job and I had my refugee travel document, which I’d received just over four years earlier, after claiming asylum at Heathrow Airport. It was all I needed. I put scans of the documents in an email and hit send.

Two hours later a woman rang me. She outlined the desperate need for cleaning staff. Her tone was calm but the gravity of the situation was clear. I asked whether I would be provided with personal protective equipment or PPE, a term I had only just become acquainted with from all my obsessive watching of the news. She reassured me that they would be taking all necessary precautions. But I was still unsure about whether I could find the courage to go through with it. Reports were coming out about how many frontline staff were becoming infected and dying. Was I really prepared to put myself in harm’s way, just at a point in my life when I thought things were becoming easier for me?

‘I had started to build myself a life beautiful for its ordinariness.’

Since claiming asylum in 2016, I had started to build myself a life beautiful for its ordinariness. Despite the legacy of PTSD symptoms – claustrophobia, a constant restlessness, nightmares and flashbacks – I was trying hard to make the most of the opportunity I’d been given and that so many other Syrians will never have the chance to experience. Weekends away, holidays to cities I had never seen before, walks in Epping Forest, nights out with friends, fulfilling work.

A future I thought I might never get the chance to have. I paused. But the voice on the phone explained that there were five hospitals in dire need of help and one was Whipps Cross – the hospital just ten minutes from my house that I walked past almost every day. The building serving the community I had grown to know – and love. My doubt evaporated. I knew I had to do it. Two days later, I found myself standing outside.

Whipps Cross is one of the oldest hospitals in London. A warren of Victorian buildings, many of them out of use, it looks like an intimidating cross between Hogwarts and an asylum. It’s a place where lives change. Sick people are healed and some of them die. On the day I arrived there were already twelve wards full of coronavirus patients, many of them gasping into oxygen masks, others unconscious and being kept alive by tubes running deep into their lungs. Helping to look after them and keep the hospital running, was an army of nurses, healthcare assistants, porters and cleaners, many working for less than the London Living Wage. In a just a few months, these frontline workers would become as dear to me as family members. People like Gimba and Albert and Pilar and Giby and Vittorio, to name just a handful. But I didn’t know any of that back then, standing at the reception entrance. All I knew was that I’d never been as terrified. Even when I’d had my bones broken. Or been shut in a windowless cell and told I would never leave. Or when I was in a leaking dinghy full of other Syrians, including many children. Or during those afternoons when I longed for my distant parents and siblings so hard I thought my heart might break. Perhaps it’s strange to say, but none of those experiences rivalled the unadulterated terror I felt that morning. I’d grown to fear hospitals after what happened to me in one of them in Syria. I vacillated, my heart racing, my throat dry. Could I? It would be so easy to walk away and pretend none of it was my problem.

Somehow, though, I found myself stepping over the threshold, powered almost unconsciously by my strongest belief: love triumphs over fear. The Red Zone. When I first went upstairs to the ward, I didn’t know what that meant. I only saw a red circle on the door. The colour of blood, stoplights, danger. Then it was explained to me that it meant that every single patient inside had coronavirus. Once you stepped through the door, you had to be wearing full PPE.

Behind the door, every bed was full. And not only with the elderly. Many patients were younger – in their forties or so. So many of them struggled to breathe, leaning back, the lower halves of their faces covered by oxygen masks, their eyes unobscured. I didn’t know if their expressions were desperate or resigned – I couldn’t bear to really look. For the first few days, I wasn’t able to make eye contact with anyone. It was clear that I was face to face with the virus.

‘As well as the vast scale of death, it was quickly clear to me how much the ward was held up by immigrants.’

As well as the vast scale of death, it was quickly clear to me how much the ward was held up by immigrants. Most of the porters, cleaners, healthcare assistants had come from other countries. It was like the United Nations. Immediately I felt like I belonged. I had spent the previous four years advocating for the rights of refugees and immigrants and here I was surrounded by them, witnessing up close their vital contribution. We had so much in common. We may not have shared a language or cultural similarities, but what united us was that we had made Britain our home and were working in that ward as a unit, to combat the virus. Risking our lives and the lives of those closest to us, to make a difference. At the points that I’ve felt closest to giving up, I’ve often been buoyed by unexpected acts of generosity. Time and time again, bright spots of goodness have helped me just when I’ve needed it most. Reminders of connection.

Despite the terrible things I have seen – from a prison cell in Syria to that ward in London – my story is one of hope, not fear. If anything, it is a simple example showing that if we unite in kindness and love – wherever we are from, whatever we look like and however much money we make – we can get through the darkest of days.

Image credit: Alice Aedy

Hope Not Fear

by Hassan Akkad

Despite having experienced the unimaginable, BAFTA award-winner Hassan Akkad holds onto hope and demonstrates the kindness humanity is capable of every day. Hope Not Fear details both Hassan's life in Syria before the war and his perilous journey to the UK as an asylum-seeker, followed by his experiences from the Covid-19 frontline as an NHS cleaner at a London hospital. His account of the pandemic has even driven a government U-turn on the exclusion of the families of NHS cleaners and porters from its bereavement compensation scheme. Hassan's story of triumph over adversity by standing together, united in kindness and love, is the most important message of our time.