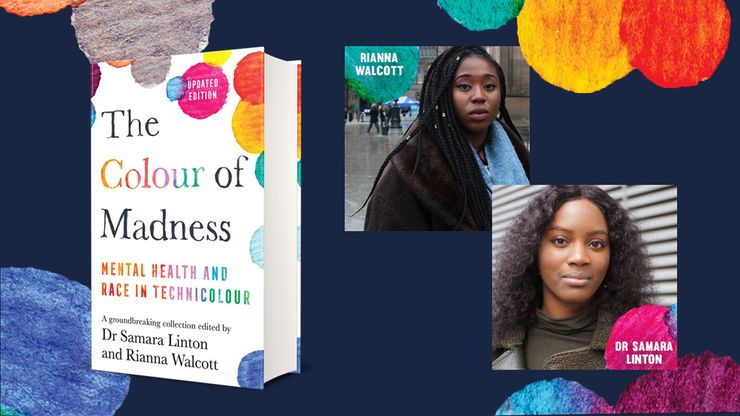

'There is no single mental health story': Samara Linton on disrupting whitewashed mental health narratives

The Colour of Madness is a groundbreaking collection of memoir, essays, poetry, short fiction and artwork, that amplifies the voices of people of colour and their experiences with mental health. Here, Samara Linton, the book's co-editor tells us how the collection came to be and selects some of her favourite contributions.

There is no single mental health story. Some of us see the world in red, some in violet, and others somewhere on the spectrum in between. The Colour of Madness is a collection of essays, stories, poetry and art by People of Colour in the UK whose thoughts and behaviours have been conceptualised as abnormal. It serves to assert the kaleidoscopic mental health experiences of People of Colour in the UK and disrupt the whitewashed mental health narrative that dominates the mainstream discourse.

The Colour of Madness was first published in 2018, but we ended our relationship with our previous publisher last year when the press was linked to a far-right group. So, unsurprisingly, we welcomed the opportunity to give the book a new lease of life with Bluebird, with many tears and open arms.

The last four years have wrought changes that we could not have imagined when we first conceptualised this collection. We’ve seen shifts in the national and international conversation around racism, governmental reports affirming our experiences of discrimination, and a fleeting moment when Black lives became a mainstream concern. Still, the Covid-19 pandemic has thrown into sharp relief the structures and systems that continue to harm racialised communities. We’ve seen how inequalities in healthcare, housing and employment allowed a virus to sweep through our neighbourhoods, leaving us grappling with grief and trauma. We’ve seen how easily People of Colour are scapegoated as carriers of the virus and producers of new variants. We’ve seen how, dismissively, our communities are labelled vaccine-hesitant and disinformation-rife with little regard for the medical racism, past and present, that causes fear and distrust.

We also acknowledge that numerous social structures, hierarchies, and intersections exist that shape individual mental health experiences under the People of Colour umbrella. The Colour of Madness provides a platform for individuals to share their unique experiences while recognising the collective disadvantage racialised people in the UK face when engaging with the mental health system.

Many have contributed to this collection from a place of lived experience and survival. As such, The Colour of Madness is inherently political. It is a resource which people can refer to and use for advocacy. When we consider that People of Colour in the UK face more inadequate mental health treatment than their white counterparts but are also more likely to be detained under the Mental Health Act and experience coercive treatment, the need for this resource is clear.

In creating The Colour of Madness, we wanted to create a lasting piece of art – an authentic collection of experiences and expressions that did not pander to a white or neurotypical gaze.

As my co-editor, Rianna Walcott, explains, ‘As a condition for making art, we were able to start from a really fruitful place. We had such a broad brief: be a Person of Colour in the UK and create a piece for us about your experiences of mental health’. And the submissions that poured in moved us in ways we could never have imagined.

‘It was such a rich place to come from,’ Rianna continues. ‘Sometimes, creating from this position of thinking about your health, your mental health and even spaces of distress is how we get some of our most lasting and beautiful pieces of art. And I think that the book demonstrates that.’

Here, Samara selects some of her favourite contributions to this vital collection:

Self-Discovery

by Mica Montana

when i tell you

that aliens have implanted

chips in my head

or that the CIA is leaving microphones

under my bed

that i

think i am Jesus,

don’t get caught on the metaphors.

don’t try to take my poetry

and fit it into your theory of psychology

In an attempt

to calculate how far away i am

from the normal way that a human being

relates to itself,

don’t lock me into your definitions of mental health.

no, i don’t actually think that i am Jesus of Nazareth

who walked the desert for forty days

and brought salvation through death.

what i am trying to communicate

is that i now recognize myself,

as important.

as having a cross to bear.

as a being made of love.

as a being, with a great purpose.

as a being, with a strong spirit.

so don’t get upset

when i refuse to let you convince me

that it is irrational to feel like a God

when i have finally encountered

my divinity

when i have promised myself

to no longer let

the demons, the CIA, the aliens,

my negative thoughts

win in their attempt to

put out my fire.

win in their attempt to silence me

or turn me into something i don’t want to be

so when i tell you

that i am fighting the aliens in my head,

that i’m getting rid of the microphones

that the CIA have put under my bed

that i

feel like Jesus.

don’t get caught on the metaphors.

simply reply,

it’s about time.

In Lingala, We Call It Liboma

by Christina Fonthes

My grandmother said it the day she found her first daughter, Mosantu, asleep in a stranger’s bed after the third day of searching. Barefoot, lips cracked from lack of water. ‘A beli liboma’.

Aunty Chantal said it when she took me to Kilburn Market. We bought three aubergines and a brown paper bag of garden eggs. Mad Mary walked past us minding her own damn business. A silver trolley full of black bin liners spilling her secret – a black-and-white photograph of her as a bride in white with a man she had not lain with in too many years. ‘A beli liboma’.

Cousin Merveille said it when Mama Pathy, the woman who sewed all of our liputas for weddings – being a woman of the word she always made the skirts longer than we asked – started cleaning the pavement outside of her house with a bucket of soapy water at 3 a.m. every morning. The council had refused to move her; they said she did not have priority. No one but her could see the blood stains from her son’s body. ‘A beli liboma’.

The barber said it the Saturday I went with Uncle Teddy to get his hair cut. The barber held his clipper up to Uncle Teddy’s head when he started recounting the story of his friend who was so unhappy with his marriage that he got up and walked out of the house during an Arsenal match without his keys or his coat and never came back. ‘A beli liboma’.

Mama said it on the phone to Aunty Lola when she thought I was asleep. It was two days after I came home. I was lying on the leather sofa in the living room. Mama was watching Nollywood and drinking Miranda. I heard the rustling of the sertraline in the pharmacy bag. ‘A beli liboma’.

Asian on a White Ward in a White Town

by Dylan Thind

As told to a family member.

I don’t feel I have much to say, so maybe you can just ask me questions.

I was sectioned because I made a serious attempt on my life. I took an overdose, but managed to stay alive and woke up in the hospital, and I was sectioned after that. I’ve been sectioned since then, fourteen months.

I’d had a very traumatic experience before this, and I’m not sure I’ve got over it. My post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is getting better, in that I don’t have flashbacks anymore, but I think with extreme trauma, especially prolonged extreme trauma, you will always carry it with you.

I’m an Asian man in my thirties on a psychiatric ward in an almost exclusively white town in the South West of England.

I do feel like an outsider in this town and on this ward. And I do feel like I’m treated differently because of my race.

For example, I love hip-hop and other similar music. But there was an incident where I recommended a song called ‘Gihad’ by a rapper called Raekwon to one of the other service users. The staff – incorrectly – said I had recommended a Jihadi video. They didn’t believe me when I said it wasn’t, and they didn’t check.

As a result of this, I got put under a one-to-one observation, when they monitor you for twenty-four hours a day and [isolate] you in your own room. I was also referred to the Prevent Programme safeguarding investigation, which they later abandoned because there was no substance to their claims.

I think they referred me because of the colour of my skin; they thought I was a Jihadi. I think it was also because I was growing a beard at the time. The staff talk in handovers but get a lot of things wrong.

Would I say this was racism? It’s difficult to know for sure, but I’d guess that it was. There are Black agency staff, but no Black or Asian permanent staff actually work on the ward; they’re all white. The ones that complained about me – they were all white. Currently, I am the only non-white patient on the ward and the longest-standing BME person.

So, that incident was the most glaringly obvious example of where I had been treated differently because of my race, but you don’t know if you’re being treated differently in more subtle ways. Like, if a white person would get away with something that I’d be told off for; you don’t know it, but you feel it. I think I feel it in general in the South West; that being on a psych ward in here I just feel the racism.

It is difficult to quantify, but racism is always bubbling just under the surface. Even if patients are nice to you, you know that if you annoyed them or something went badly, they would turn to racism. So, you always have to be really careful. Especially with the harder, tougher patients.

There once was a guy that told me a very offensive, racist joke, I think to get a reaction from me. And there was another patient who thought I was a terrorist; she constantly asked me if I’d been to Guantánamo Bay. It made me feel like an outsider – someone that is not British. I tried to tell the staff about this, the head nurse, and she just said that the patient’s very unwell at the moment. I think I always feel like an outsider, especially when I’m in the South West and more so on the ward. I think it’s because I’m Asian and I do visually appear different to the other people on the ward. But there are some lovely patients on the ward who do include me.

Also, I remember the time one of my relatives asked me to change into my jeans from my tracksuit bottoms before we went out because it was cold. The nurse said, ‘I don’t know what they do in your culture, but in our culture, you can dress the way you want to.’ My relative was just trying to help, so I didn’t get cold outside.

You’re asking me if being Black or Asian predisposes people to more mental health problems. It’s a good question. From what I know, Black people are disproportionately more likely to develop schizophrenia, and Asian people are more likely to develop depression. It is so complex to try to work out exactly why this is, but I think that being visibly different makes you quite self-conscious and quite introverted, and these traits I think can lead to depression.

And I think when you get a lot of racist abuse, you turn anger inwards when you can’t really fight back, and lots of anger turned inwards can lead to depression as well.

I really think that someone from a BME background living in a white town is likely to develop some sort of mental health issue. With me, I was trying to fight against it, but it inevitably caught up with me. When I had my trauma a few years ago, everything came up to the surface.

I don’t feel that the white psychiatrist I’ve had from the start understands me. Everything I say he will dismiss as delusion. And he’s convinced that antipsychotics will change my thinking. But my thinking is based on truth and my experiences, and no kind of pill can change what happened to me. I suppose therapy would be more conducive than a tablet.

The psychiatrist has a very pharmaceutical idea of happiness. He believes that ramping up the chemicals will solve my problems. He’s very much ‘by the book’, and the things that I try to tell him, like about kundalini* experiences and things of that nature, get instantly dismissed as a delusion.

There are experiences outside the medical model that are just as valid. Kundalini is a Hindu thing. I think that’s another reason why a white psychiatrist will not understand the experiences of someone from a different culture. A more modern, open one could, but they would have to be someone who really does their research about all sorts of experiences.

There is a Black psychiatrist who is not that much better but seems more caring. But he also just sanctions more pills. I do think that some of this is the result of [being in a provincial town]. The majority of nurses have never lived away from here – it’s true, I’ve asked – and so, they’ve never really had their experiences broadened by other cultures, by other art, by other knowledge.

I find boredom on the ward the most difficult thing to deal with. When the kundalini left my body, or when I developed psychosis, it took away all my creativity, so now I find it very difficult to write – which is why you are writing this up for me. And I find it hard to do all the things that used to keep me occupied. It made my mind quite slow and sluggish, so now I have a tendency to be bored a lot.

You’re telling me that what I’m saying and have told you shows someone who is very creative and articulate. I don’t feel it’s creative.

I’d like to have more things to do on the ward. At the moment, we all just feel contained, we’re given no real help. When you ask one of the staff for something, they act like they’re doing you a favour. A lot of the time, they’ll ask you to wait for five or ten minutes, and when you look inside the office, they’re doing nothing but having a chat. There have been good nurses, but I find all the best ones tend to leave. There is one great activity coordinator because he really cares. More caring staff would be good.

The staff could be more empathic. There seems a lack of empathy on the ward. If someone is crying, most of the staff will just walk past them and not do anything. It last happened yesterday with a girl called Julie who is very emotional and cries a lot. I don’t think she gets treated well by the staff; they don’t know how to handle her.

For example, there was one time she was sick in the toilets and rather than asking her if she was okay, or if she needed anything, the nurse just said, ‘Have you just been sick? You’ve missed a bit, clean it up,’ and was really angry at her. The nurse shouted it in front of everyone in the corridor. Julie started crying. She gets bad anxiety, which was why she was sick. She’s only very young.

Everyone is bored in here, and they don’t know what to do with their time. I want to be discharged, but they have not given me a definitive date. They must think I’m a risk to myself, but I don’t think I am now. I feel better. Although I don’t feel as good as I used to feel.

I used to have a really good job before the trauma. Before, I was working for what was considered at the time the best startup to work for. My mind was working very sharply; I was able to do very complex coding work. It wasn’t mania; it was kundalini. I lived in a really cool part of the city, had great housemates and lots of friends.

Now things are completely different. Before, if I checked my Facebook, there would be ten or eleven invites for all sorts of arty things. Now, I don’t have invites for anything. If you’re out of the city for long enough, you just get forgotten about. But I have a lot of friends who still contact me and stay true to me.

In the future, I’d like to be discharged and slowly be able to build my life again. My friends and family would help me build my life again; having something to work on, like a project, would help. I think the future’s going to be hard: I’ve changed and will always carry the scars. But I hope things can get better.

* Kundalini, a Sanskrit word meaning coiled serpent. It refers to the primal, creative energy that is said to reside at the base of the spine.

The Colour of Madness

by Samara Linton

The Colour of Madness is a groundbreaking collection that amplifies the voices of people of colour and their experiences with mental health.

These are the voices of those who have been ignored. Updated for 2022, The Colour of Madness is a vital and timely tribute to all the lives that have been touched by medical inequalities and aims to disrupt the whitewashed narrative of mental health in the UK. A compelling collection of memoir, essays, poetry, short fiction and artwork, this book will bring solace to those who have shared similar experiences, and provide a powerful insight into the everyday impact of racism for those looking to further understand and combat this injustice.