Actor David Harewood on the impact of racism on mental health

David Harewood reflects on the psychotic breakdown that could have taken his life and his journey to understanding its roots – the struggle of growing up Black and British.

When critically acclaimed actor David Harewood was twenty-three, his acting career beginning to take flight, he experienced what he now understands to be a psychotic breakdown and was sectioned under the Mental Health Act.

Looking back at his early life and trying to make sense of this breakdown during the filming of the award-winning BBC documentary Psychosis and Me, David uncovered how his experiences growing up Black and British had contributed to a rupture in his identity, ultimately leading to the unravelling of his mind.

David also came to realize that he was far from alone. The response to the documentary made him recognize that what had happened to him was common, but rarely talked about, and further investigation into the facts around Black mental health in the UK revealed that Black Brits are disproportionately affected.

Here, David shares how he came to understand the roots of his breakdown and why he believes in the vital importance of reducing stigma around psychosis.

Thirty years ago, fresh out of drama school, I had what I now understand to be a psychotic breakdown. I spent weeks walking all over London, sometimes throughout the night, talking to complete strangers and following them wherever they led me. I’d black out only to regain consciousness in a completely different part of town, hours later, afraid and with absolutely no idea what had happened in the interval. Had it not been for some extraordinary friends who decided amongst themselves that I needed to be hospitalised, I might have vanished into the London night for good. Worse still, I could have taken heed of the incredibly real and convincing voices in my head and simply thrown myself off Westminster Bridge. Instead, I found myself sectioned under the Mental Health Act and kept on a locked ward. Nobody was willing or able to offer any explanation for what I was experiencing.

When I look back, it’s clear that I came close to death. Many men, Black men in particular, have died being restrained by the police whilst experiencing psychotic symptoms. I’m absolutely convinced that had I been in America at the time of my breakdown, I’d most likely be dead. I’m acutely aware of just how much I struggled against those trying to subdue me when I was sectioned. It took not one or two but six police officers to hold me down. One false move by me or any of them could have ended my life.

Although I was hospitalised twice in quick succession, I only recovered my sanity at home with my caring, nurturing mother. After those terrifying episodes, I managed to continue my career as an actor remarkably quickly, becoming the first Black actor to be cast as Othello at the Royal National Theatre, as well as appearing in a string of acclaimed international theatre productions. I also played a critical role in the Emmy and Golden Globe-winning American drama series Homeland and bagged a Spirit Award nomination for Best Actor. I guess you could say it has been quite the turnaround!

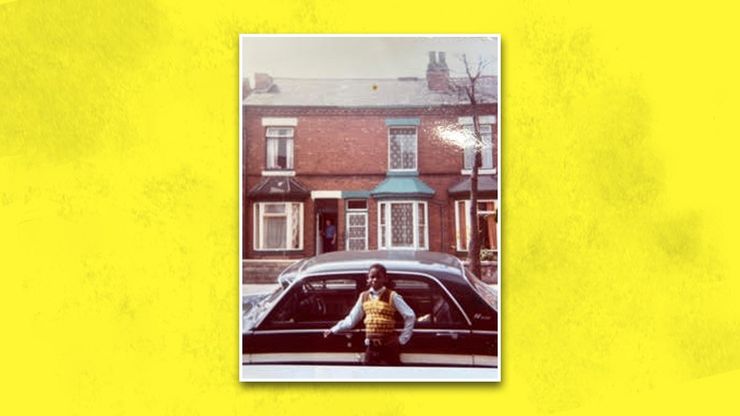

I’ve never made a secret of my former mental health troubles. In fact, the story of my breakdown has been a late-night tale told to drunken friends. But I had no idea of the significance of my journey into madness until a couple of years ago when I decided to examine the facts in the award-winning BBC documentary Psychosis and Me. During filming I discovered the extent of my breakdown and began to understand its roots. I was confronted with the unbearable pain and confusion from that time in my life, when I was just twenty-three years of age. A pain buried so deep in my subconscious that its existence was a barely remembered dream. Delving into the causes of my breakdown has involved reconnecting with my struggle to forge a sense of identity and belonging as a Black British man, and the many conflicts I had experienced around race, nationality and acceptance all came flooding back and took me right to the moment my uncertainty began: my first direct experience of racist abuse. That single encounter shattered my perception of myself, splitting my identity in two. A small crack appeared, perhaps just the faintest fissure at first, but over the years it grew wider and wider. Caught between the two halves of my identity, I disappeared into the space between and woke up in a mental institution. I had completely lost my mind.

The public reaction to Psychosis and Me took me completely by surprise. All sorts of different people approached me in the street to recount their own experiences of psychosis. I realised that rather than being isolated in my experience, countless people had sons, daughters, mothers and fathers who had lived through something similar themselves. They were thankful that I had spoken out. I began to recognise that what had happened to me was very common, but rarely talked about. There didn’t seem to be a language in which people could easily discuss the topic. MIND, the mental health charity, informed me that the night the film aired, calls about psychosis rose by 107 per cent. Little did I realise that the documentary was just starting to lift the lid on my own understanding of the past.

The stigma surrounding psychosis is intense and many are either too embarrassed or ashamed to talk about or admit their experience. This reluctance strikes me as odd, because I’ve always seen my breakdown as a truly remarkable event in my life. It helped unlock my understanding of myself, a process that is ongoing to this day.

It was only after making the documentary and talking about it that I learned the shocking facts about Black mental health in the UK. According to the latest government figures, Black people are four times more likely to be detained under the Mental Health Act than white people and are far more likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia and psychosis. Out of sixteen specific ethnic groups, Black Caribbean people have the highest rates of detention in psychiatric hospital. Clearly, there is something about living in Britain that is tough for Black people.

‘Clearly, there is something about living in Britain that is tough for Black people. ’

I can certainly attest that even on a purely professional level it’s been difficult for me as a Black actor. Back when I first started out, there were very few good roles for Black actors on television outside the narrow band of law and order figures, roles which rarely had depth or authority. Whilst on stage I could look forward to tackling complex Shakespearean characters night after night, on television it was another world entirely. Over the years this would frustrate me and, as the parts dwindled, I feared things were pretty much over. Thankfully America came calling just in time. The weekend I jetted off to shoot the pilot episode of Homeland I was down to my last eighty quid!

I understand what it’s like to be skint, to lack opportunities, to see others getting ahead of you. I’ve also experienced racism, both overt and subtle, and I’ve been outspoken about it, too. Britain has deep pockets of racism and that may surprise some, but not me. Without doubt the impact of racism can contribute to the development of psychosis. Denying this basic reality risks pushing people of colour further and further away from mental health services and away from the help they so desperately need. The numbers don’t lie.

My own breakdown was a cry for help that I couldn’t appreciate at the time. Uncovering its origins while writing this book has been difficult, but what I have discovered has given me an immense freedom. Now it’s possible to consider my entire life from a whole new perspective. In moving through post-traumatic stress, I have even discovered some ‘post-traumatic growth’. I’m grateful for the opportunity to understand the root of my insecurities and vulnerability and I have written this book as an attempt to help other people connect mental ill-health to something beyond themselves.

‘There are many Black men, in particular, who continue to be affected by these issues but avoid getting the support they need because of traumatic experiences with mental health services. ’

I was extremely lucky to survive my brush with psychosis and, although I was sectioned twice in short succession, I have never had any further episodes or needed further medication. That’s not true for everyone. There are many Black men, in particular, who continue to be affected by these issues but avoid getting the support they need because of traumatic experiences with mental health services. Other chronic sufferers find themselves trapped in a cycle of hospitalisation, poverty and, often, crime. This can be an impossibly hard pattern to break and when racism is thrown into the mix, the emotional build-up can have explosive and sometimes dangerous consequences.

As a Black British man I believe it is vital that I tell this story. It may be just a single account from one person of colour, but my hope is that it might be enough to change some opinions or, more importantly, stop someone else from spinning completely out of control.

Maybe I Don't Belong Here

by David Harewood

Today, critically acclaimed actor David Harewood is well-known for his starring roles in shows such as Homeland and Supergirl. But at the age of just 23, freshly graduated from drama school, David experienced a psychotic breakdown, and was sectioned under the Mental Health Act. In this hugely powerful and provocative account of a life lived after psychosis, David uncovers devastating family history and investigates the very real impact of racism on Black mental health. Moving, candid and insightful, it's a must-read memoir for 2021.