Writing my culture: a view from the margins

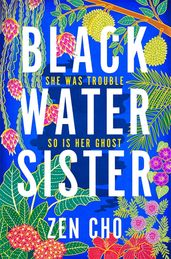

'There is a disparity in terms of what authors of different backgrounds are expected or required to explain.' Zen Cho, author of Malaysian-set fantasy ghost story Black Water Sister, on the pitfalls and challenges of immersing readers in her culture.

The issue of who is at the margins pivots on the individual's point of view. Here, author of award-winning fantasy books, Zen Cho describes the pressure of explaining her culture to outsiders, and how to avoid weighty contextual descriptions which will alienate the reader from the heart and soul of her stories. Instead she invites readers into a world in which they may not understand every cultural reference, but where the characters and the tale will have them hooked.

I don't think of myself as writing from the margins most of the time. I write about the things that are important and interesting to me, and of course I am the centre of my own world, so in that sense I'm always writing from the centre.

But as a non-Western, non-white writer operating in a Western market, I receive regular reminders that my centre is marginal to many people. One of the primary forms these reminders take is the question: how much do you explain? It's a question I had to grapple with when working on my Malaysian-set contemporary novel Black Water Sister.

‘As a non-Western, non-white writer operating in a Western market, I receive regular reminders that my centre is marginal to many people.’

Creators deal with this question in different ways:

- Footnotes, as seen in Kevin Kwan's Crazy Rich Asians (so I'm told – I haven't read it yet) and Lauren Ho's Last Tang Standing (Bridget Jones if she was a high-powered lawyer in Singapore – very entertaining).

- Glossaries. In my "home genre" of science fiction and fantasy, we're very familiar with these – they help us understand that s'fghan is a horse-like creature with webbed feet and rainbow wings. In the context I'm discussing, though, they're used to explain words like baju or lengkuas.

- In-text explanations. "I went to my grandmother's house first, as in our culture respecting our elders is very important." I call this the "nasi lemak, i.e. rice cooked in coconut milk and kill me now" style.

The third approach is my least favourite, because it's the most disruptive to the reader's suspension of disbelief. When you're from a 'non-traditional' background, books about your culture, even ones written by cultural insiders, often have this self-consciousness to them – you might call it the Western gaze, by analogy with the male gaze. These in-text explanations of words, objects and concepts the characters themselves understand are carriers of that Western gaze. They make it obvious that the narrator is addressing someone outside the book, someone to whom the characters' conversations, customs, thinking and way of life are somehow alien.

You may argue that the writer's chief responsibility is to ensure that readers can understand the story being told. This raises the question of how much of a work needs to be readily legible in order for it to be considered understandable.

If I write a book about Malaysia in the hope non-Malaysians will read it, must it be written in such a way that non-Malaysian readers will understand every single word? Because I and other Malaysians grew up assuming there would be multiple references in any given book that we'd miss – references to unfamiliar food, places, concepts, pop culture, etc etc etc. Of course, this is a question of degree; I'm sure several people reading this might say, 'I didn't understand x in y book by a British author, and I'm British.' My point is that there is a disparity in terms of what authors of different backgrounds are expected or required to explain, and that disparity has its roots in larger power imbalances.

‘There is a disparity in terms of what authors of different backgrounds are expected or required to explain, and that disparity has its roots in larger power imbalances.’

It's an issue that extends its tendrils into matters of craft, too. One common editorial ask, when you're writing about places and cultures unfamiliar to the Western audience, is for more description of the food, buildings and material culture depicted. To be clear, I consider this a reasonable editorial request, and on one level it's a legitimate writing craft issue – I need to work on description so the book conveys a fully realised setting.

On the other hand, one could point out that white authors are not asked to describe beer in exhaustive detail every time their characters mention going to the pub. Admittedly, crumpets were turned into muffins in the American editions of Harry Potter – but you can bet they weren't transfigured into lempeng for the Malaysian editions.

This is also a matter of genre conventions. Nobody asked me to describe what cold souse was when it was mentioned in passing in my debut novel Sorcerer to the Crown, a historical fantasy set in Regency London. This was even though it's significantly easier to get an image of nasi lemak by Googling than it is to get an idea of what cold souse looks like. (Cold souse is lightly pickled pork brawn, by the way, and to this day I don't actually know what it looks like either.)

The reason why I didn't have to explain cold souse in Sorcerer was because readers of Regency romances and historical fantasy expect casual references to foodstuffs they aren't familiar with. It's part of the pleasure of the reading experience. The problem with Black Water Sister is that the only comparable books in the Western market do explain. Novels set in Southeast Asia are effectively treated as travelogues, a chance for the assumed Western reader to explore an exotic destination.

What I was trying to do with Black Water Sister is a little different from that. It's no different from what many novelists are aiming to achieve. I'm inviting you into the world of my main character Jess – a world she and I know well, but not perfectly; a world in which we are both insiders and outsiders. Like us, you may not understand everything you hear, or recognise everything you see. But you'll learn as you go along. By the end of the book, you and I will hopefully understand each other better. Isn't that one of the purposes of literature?

Black Water Sister

by Zen Cho

Broke, jobless and just graduated, Jessamyn is abandoning America to return ‘home’. But as she packs to return to Malaysia, a country she hasn't seen since she was a toddler, she starts to hear a bossy voice in her mind, which belongs to her late grandmother Ah Ma who in life, and apparently in death, worships a local deity, the Black Water Sister. When a business magnate dared to offend her goddess, Ah Ma swore revenge, and she isn't afraid to blackmail her granddaughter into helping her to make mischief.