25 of the best horror books and ghost stories

Feel the chills with our pick of the scariest horror books and ghost stories stories to read right now.

Gothic, psychological, supernatural, slasher: there's more than one way to be scared. From the suspense of Adam Nevill to the body horror of Clive Barker, if you're looking for a new horror novel, you're in the right place with our pick of the best horror books.

The Works of Vermin

by Hiron Ennes

This intricate horror adventure takes you deep into a tale of monsters and court politics. In the decadent city of Tiliard, exterminator Guy Moulène takes on a vile job to keep his sister out of debt, hunting uncanny pests that crawl from the river. His latest target is different: a worm the size of a dragon with a ravenous taste for artwork. As it begins to eat the city, its toxin reshaping the residents and their future, Guy decides that no sane person would hunt it, if they had a choice. But he doesn't.

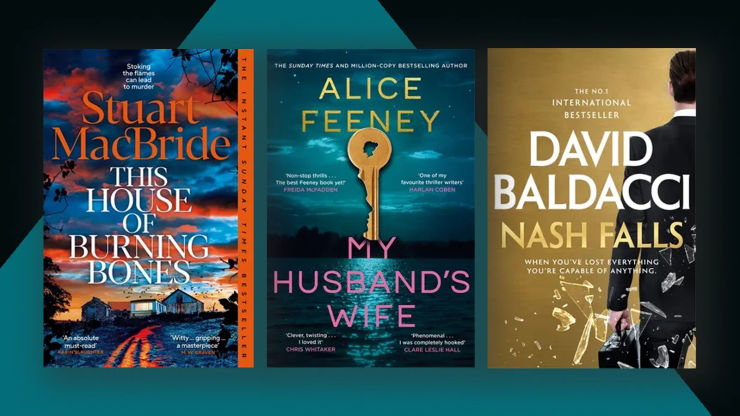

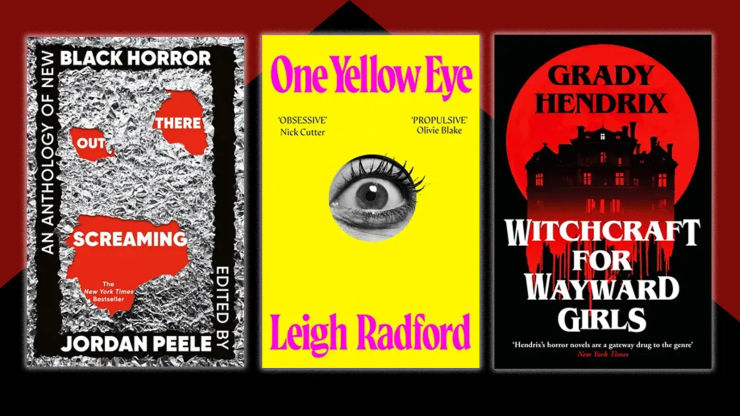

One Yellow Eye

by Leigh Radford

This razor-sharp horror debut blends heartbreak, dark humour, and the grotesque in equal measure. Kesta, a scientist, is hiding her undead husband Tim – the last person to have been bitten in a zombie pandemic – in her spare room while she races to find a cure. As the world breathes easy, believing the infection contained, Kesta is under increasing strain, stealing drugs and facing the ever-present risk of discovery. With time running out, will she be able to cure her husband – or will they trigger another outbreak?

Witchcraft for Wayward Girls

by Grady Hendrix

Get ready for the new Southern Gothic horror from the author of How to Sell a Haunted House and The Final Girl Support Group. It's 1970 in St. Augustine, Florida, and fifteen-year-old Fern has just arrived at Wellwood House, a 'home' for unwed mothers. Every second of Fern and the other teenagers' days is controlled by adults who claim to know what's best. Then Fern is given a book about witchcraft, and power changes hands. But there's always a price to be paid. And it's usually in blood.

Incidents Around the House

by Josh Malerman

Bela is eight, and lives happily with her family. There's Mommy, Daddy, Grandma Ruth. And Other Mommy. . .who is getting a bit tired of asking Bela the same sinister question over and over and not getting a response. As horrifying incidents around the house indicate that time is running out, only the bonds of family can keep Bela safe – but it seems her parents' marriage may not be as stable as first thought. The safety Bela relies on is about to unravel. And Other Mommy needs an answer.

No One Gets Out Alive

by Adam Nevill

Now a major Netflix film, this is the perfect read for fans of psychological horror. The story follows Stephanie Booth, a cash-strapped young woman who thinks she's found a bargain with a room at 82 Edgware Road. But this is no ordinary house, and its terrifying atmosphere, disturbing landlord, and strange sounds soon escalate into a nightmare from which she may never escape.

Out There Screaming

by Jordan Peele

Jordan Peele, the visionary writer and director, curates this groundbreaking anthology of brand-new stories of Black horror, exploring not only the terrors of the supernatural but the chilling reality of injustice that haunts our world. A cop begins seeing huge, blinking eyes in place of the headlights of cars that tell him who to pull over. Two freedom riders take a bus that leaves them stranded on a lonely road in Alabama where several unsettling somethings await them. A young girl dives into the watery depths in search of the demon that killed her parents. These are just a few of the worlds of Out There Screaming.

Leech

by Hiron Ennes

In an isolated, icebound community, a doctor kills himself. The replacement, sent by the Interprovincial Medical Institute, discovers a parasite living in the corpse. But how did it survive, when the doctor was already possessed? And who exactly are the Interprovincial Medical Institute? If Poe wrote about parasites, he'd be on his way to Leech. This is an atmospheric gothic horror from a terrifying new voice.

American Psycho

by Bret Easton Ellis

On the surface, Patrick Bateman is living the dream: a job as a stockbroker, dinner dates every night at the latest restaurant in town, a string of admirers. But behind the pristine façade lurks a psychopath. It's hard to know which element of Patrick's increasingly sadistic murderous rampage around New York is the most horrifying. The explicit violence. The unsettling feeling of not being entirely sure what's real and what's imagined. The void at the heart of our nightmarish protagonist. Or the implication that the same void sits at the heart of us, too.

Hare House

by Sally Hinchcliffe

In the first brisk days of autumn, a woman arrives in Scotland having left her job at an all-girls school in London in mysterious circumstances. Moving into a cottage on the remote estate of Hare House, she begins to explore her new home. But among the tiny roads, wild moorland, and scattered houses, something more sinister lurks: local tales of witchcraft, clay figures and young men sent mad. Striking up a friendship with her landlord and his younger sister, she begins to suspect that all might not be quite as it seems at Hare House . . .

The Upstairs Room

by Kate Murray-Browne

Eleanor and Richard have stretched themselves to the limit to buy the perfect home. But the cracks are already starting to show. Eleanor is unnerved by the eerie atmosphere in the house and she is convinced it is making her ill. Their two young daughters are restless and unsettled. Richard, on the other hand, is more preoccupied with Zoe, their alluring young lodger, who is also struggling to feel at home. As Eleanor's symptoms intensify, she becomes determined to unravel the mystery of the family who lived in the house before them. Who were the Ashworths, and why is the name Emily written hundreds of times on the walls of the upstairs room?

White is for Witching

by Helen Oyeyemi

High on the cliffs near Dover, the Silver family is reeling from the loss of Lily, mother of twins Eliot and Miranda, and beloved wife of Luc. Miranda misses her with particular intensity. Their mazy, capricious house belonged to her mother’s ancestors, and to Miranda, newly attuned to spirits, newly hungry for chalk, it seems they have never left. Forcing apples to grow in winter, revealing and concealing secret floors, the house is fiercely possessive of young Miranda. Haunting in every sense, White is for Witching by Helen Oyeyemi is a spine-tingling tribute to the power of magic, myth and memory.

The House on Cold Hill

by Peter James

Evil isn't born. It's built. The House on Cold Hill is a chilling and suspenseful ghost story from the multi-million copy bestselling author, Peter James. Moving from the heart of the city to the Sussex countryside is a big undertaking for born townies, Ollie Harcourt, his wife, Caro, and their twelve-year-old daughter, Jade. But when they view Cold Hill House – a huge, dilapidated, Georgian mansion – they are filled with excitement. But, within days of moving in, it becomes apparent that the Harcourt family aren't the only residents in the house . . .

The Ice Lands

by Steinar Bragi

Set against the backdrop of Iceland's volcanic hinterlands, The Ice Lands follows four thirty-somethings as they embark on an ambitious camping trip. As their jeep hurtles through the wilderness, an impenetrable fog descends, causing them to suddenly crash into a rural farmhouse. Seeking refuge from the storm, the friends discover that the isolated dwelling is inhabited by a mysterious elderly couple who barricade themselves inside every night. As the merciless weather blocks every attempt at escape, they soon begin to wonder whether they will ever return home.

Jaws

by Peter Benchley

The book that got millions of people out of the water. Although perhaps best known now as the Steven Spielberg film, the just-as-terrifying original novel has sold over twenty million copies. Set amongst the holidaymakers of a small Atlantic resort, the terror begins with a body, or what's left of it, washing up on the beach. And whilst the famous shark provides the gore, it's the behaviour of those in authority which offers the shocks.

The Magic Cottage

by James Herbert

Step inside The Magic Cottage, a chilling classic from the Master of Horror James Herbert. A cottage was found in the heart of the forest. It was charming, maybe a little run-down, but so peaceful – a magical haven for creativity and love. But the cottage had an alternative side – the bad magic. What happened there was horrendous beyond belief . . . Sinister sects, hideous creatures, 'healings' – be entertained and horrified in equal measure by this unpredictable classic chiller.

The Scarlet Gospels

by Clive Barker

Clive Barker may be most famous for his strange, visceral body horror films (Hellraiser, Candyman) but as true Barker aficionados know, these were actually adaptations of his books. The Scarlet Gospels is a return to the world and characters of Hellraiser. The Cenobite Hell Priest known as Pinhead is making his way around Earth killing the last remaining magicians and gorging on their knowledge with the intention of taking over Hell. Then Private Investigator Harry D' Amour inadvertently opens a portal between Hell and Earth. . .

The Ritual

by Adam Nevill

It was the dead thing they found hanging from a tree that changed the trip beyond recognition. Four friends attempting to re-find common ground on a hiking trip take a shortcut they may live to regret. If they're lucky. Lost in the Scandinavian wilderness, they take shelter in an isolated house full of macabre remains and pagan rituals. There's something of the Blair Witch to this menacing, suspenseful novel from Adam Neville which uses the power of suggestion and a creeping sense of claustrophobia to terrifying effect.

The Wicker Man

by Robin Hardy

A novelization of the haunting Anthony Shaffer script, which drew from David Pinner's Ritual, it is the tale of Highlands policeman, Police Sergeant Neil Howie, on the trail of a missing girl being lured to the remote Scottish island of Summerisle. As May Day approaches, strange, magical, shamanistic and erotic events erupt around him. He is convinced that the girl has been abducted for human sacrifice. Yet he is soon to find that he may be the revellers' quarry . . .

Pandemic

by Robin Cook

For those ready to revisit the horror of a deadly virus, this is an eerie, explosive read from the writer who invented the medical thriller. When a seemingly healthy woman dies after a respiratory attack on the New York subway, forensic pathologist Jack Stapleton uncovers some surprising findings about the cause of death. When further cases start to occur around the city, and then the world, Jack realises a new virus may be circulating, and enters a race against time to discover the link that connects all the victims.

Lovecraft Country

by Matt Ruff

Now an HBO Series from J.J. Abrams, Misha Green and Jordan Peele (director of Get Out), Lovecraft Country combines the mundane terrors of white America with malevolent spirits and a secret ritualistic cabal to entertaining and thought-provoking effect. In 1950s Chicago, Army veteran Atticus Turner sets out to find his missing father, alongside his Uncle George and childhood friend Letitia. They're aiming for New England, and the home of Samuel Braithwaite, heir to the estate that owned one of Atticus's ancestors, and what they find there is even more sinister than they imagined.

Dracula

by Bram Stoker

Bram Stoker's creation may not be the first literary vampire, but he's certainly the most famous. Whilst Dracula and his nemesis, Van Helsing, are regularly reinterpreted, updated and adapted, the original novel is very much of its time. Told via letters, diary entries and newspaper articles, it explores and reflects the fears that dominated Victorian society – the corruption of morality, unrestrained sexuality, irrationality and the foreign. But don't let this fool you into thinking it won't frighten the twenty-first century reader just as much.

Tales of Mystery and Imagination

by Edgar Allan Poe

This collection of Poe's work contains some of the most exciting and haunting stories ever written. They range from the poetic to the mysterious to the darkly comic, yet all possess the genius for the grotesque that defines Poe's writing. They are peopled with neurotics and social outcasts, obsessed with nameless terrors or preoccupied with seemingly unsolvable mysteries. The Tell-Tale Heart and The Fall of the House of Usher are key works in the horror canon, and collectively these tales represent the best of Edgar Allan Poe's prose work before his premature death in 1849.

Frankenstein

by Mary Shelley

One of BBC's 100 Novels That Shaped Our World. Frankenstein is the most famous novel by Mary Shelley. Victor Frankenstein, a brilliant but wayward scientist, builds a human from dead flesh. Horrified at what he has done, he abandons his creation. The hideous creature learns language and becomes civilized but society rejects him. Spurned, he seeks vengeance on his creator. So begins a cycle of destruction, with Frankenstein and his 'monster' pursuing each other to the extremes of nature until all vestiges of their humanity are lost.

The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and other stories

by Robert Louis Stevenson

Why has the mild mannered Dr Jekyll suddenly begun to associate with the ugly and violent Mr Hyde? And why are they never seen together? When Jekyll’s old friend Utterson tries to solve these mysteries he uncovers a horrific story of suffering and brutality that eventually leads to the terrible revelation of Mr Hyde’s true identity. Accompanied here by three other memorable stories of horror, murder and the supernatural, The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde is a masterpiece of Victorian Gothic literature.

The Turn of the Screw and Owen Wingrave

by Henry James

A young governess is employed to look after two orphaned siblings in a grand country house. Isolated and inexperienced, she is at first charmed by the children – but gradually suspects that they may not be as innocent as they seem. She soon begins to see sinister figures at the window, but do they exist solely in her imagination, or are they ghosts intent on a terrible and devastating task? The Turn of the Screw by Henry James is one of the most famous and eerily equivocal ghost stories ever written.

In this episode of Book Break, Emma recommends the best horror books for Stephen King fans.

Sink your teeth into the most exciting vampire books.