Killer crabs, deranged slashers and Pinhead: bestselling author Grady Hendrix takes us on a tour of British horror

The How to Sell a Haunted House and The Final Girl Support Group author takes us on a whistle-stop tour of British horror writing.

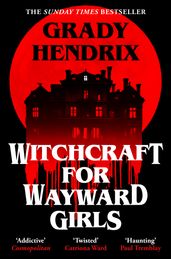

Bestselling writer Grady Hendrix knows his horror. The author of nine novels, including new Southern Gothic Witchcraft for Wayward Girls, Hendrix has also written a history of '70s and '80s horror fiction, Paperbacks from Hell. Here he takes in nihilistic rats and books of blood on a trip through British horror writing.

Horror didn’t exist as a literary genre until 1967 when Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby hit it big, followed in quick succession by The Exorcist and Thomas Tryon’s The Other. Their success (and the success of their film adaptations) showed publishers that there was gold in the horror hills, and an avalanche of horror novels crashed down onto bookstore racks throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s before sputtering out in the mid-90s.

But that was in the United States. As an American, I assumed the history of modern horror in the UK would follow a pretty similar trajectory, only with posher accents and more servants. Turns out, horror in Great Britain was so much more disreputable than I ever dreamed, and the year everything exploded wasn’t 1967, but 1974.

‘As an American, I assumed the history of modern horror in the UK would follow a pretty similar trajectory to that in the US, only with posher accents and more servants. Turns out, horror in Great Britain was so much more disreputable than I ever dreamed.’

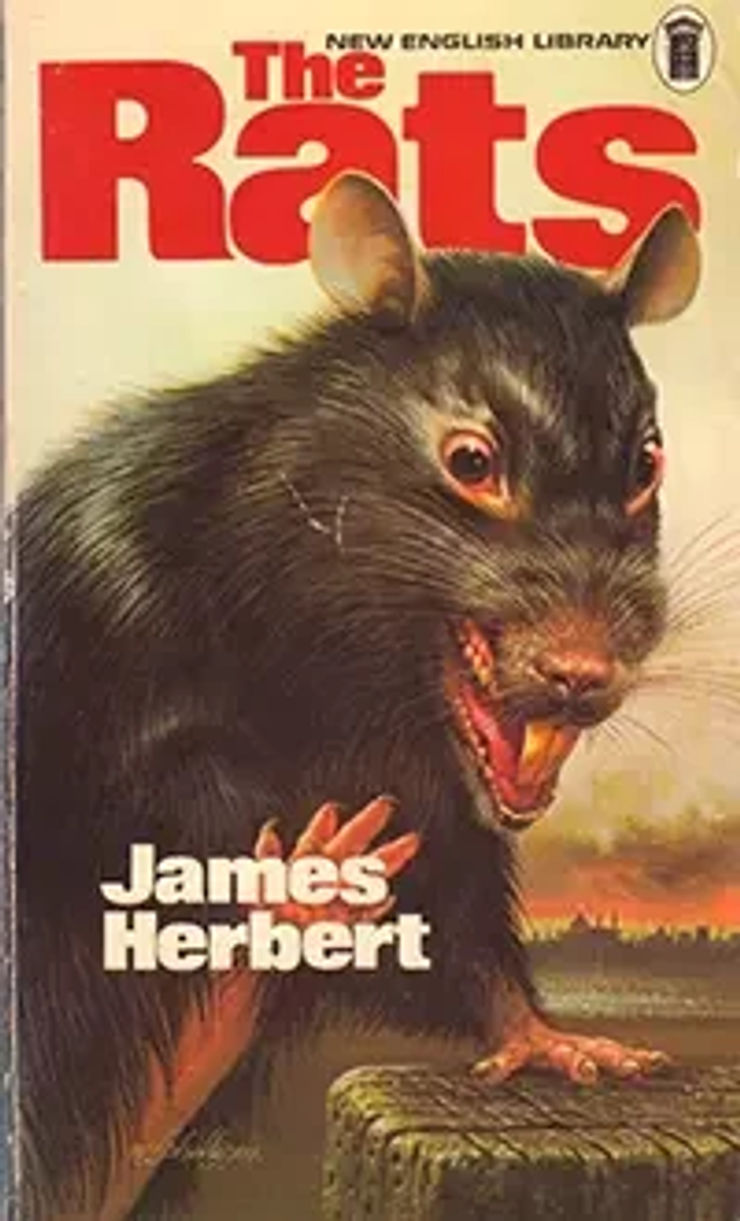

Over in the US, ’74 saw Peter Benchley’s horror novel, Jaws, about an extremely stressed out shark eating its feelings, latch onto the New York Times bestseller list and hang on tight for forty-five weeks before becoming a hit film in the summer of ’75. But back in the UK, a 31 year-old advertising copywriter had written his first novel which would gnaw its way into infamy when it was released in 1974 – The Rats.

James Herbert became one of the most successful writers in the UK, with 54 million books sold worldwide, and The Rats was a proto-punk rager that hit readers in the face like a broken pint glass. Angry, gruesome, and nihilistic, its titular rats ate everything (Puppies! Babies! Schoolchildren!) until a blue collar Man of Action shoved effete government bureaucrats to one side and beat the rats to death with his bare hands.

No one saw this coming. The UK had a long legacy of ghost stories, from Charles Dickens’ emotionally moving A Christmas Carol to M.R. James’ sinister, understated tales like “Casting the Runes.” There was nothing emotionally moving or understated about Herbert’s rats, which arrived screaming and biting and spawned a wave of animal attacks books that saw everything that walked, hopped, swam, or flew try to eat British people: Bengal tigers (Man-Eater, 1977), crabs (Night of the Crabs, 1976), jellyfish (Slime, 1984), and bunny rabbits (The Folly, 1978). There was even a mini-boom of rabies novels in the late ‘70s that coincided perfectly with the UK's stress over entry into the European Common Market (Saliva, 1977; Rabid, 1977; Rage, 1978).

British horror had flirted with outrage before. Hammer Films’ first shockers like Curse of Frankenstein and Dracula may seem quaint now, but when they came out in the late ‘50s they resulted in knock-down, drag-out fights with the British Board of Film Certification. When the BBFC read the script of Curse of Frankenstein they hit the roof, appealing to national pride in one censor’s report, “This is a loathsome story and I regret that it should come from a British team.”1 (To get an idea of how quickly things change, you can read a BBFC report on the script of Hammer's The Mummy from one year later in 1959.)

By trimming scenes and conducting diplomacy over glasses of scotch in their clubs, the men behind Hammer navigated the BBFC and their horror films became huge hits, unleashing a national hunger for gorier fare and paving the way for publishers like Pan to issue the first volume of their famed anthology series, The Pan Book of Horror Stories in 1959 (it would eventually stretch to thirty volumes). More so even than in the US, Pan’s anthologists had a deep bench of homegrown authors to pick from including Peter Fleming (Ian Fleming’s big brother), C.S. Forester (author of the Horatio Hornblower series), and Nigel Kneale (a Manxman whose Quatermass Experiment released in 1955 was the first modern British horror film). By the time 1974 rolled around, British readers were ready for something outrageous.

‘By the time the Eighties came around, British horror had two new torchbearers, writers who had grown up on Hammer Films and wanted to make horror both more literary (goodbye, killer crabs) and more extreme (so long, BBFC): Ramsey Campbell and Clive Barker.’

Two paperback publishers surfed that Seventies outrage wave: New English Library and Sphere. Spawning legions of paperbacks dedicated to skinheads running wild, The Dennis Wheatley Library of the Occult, and softcore porn, they kept newsagent shelves rowdy for years. But by the time the Eighties came around, British horror had two new torchbearers, writers who had grown up on Hammer Films and wanted to make horror both more literary (goodbye, killer crabs) and more extreme (so long, BBFC). The first of these was Ramsey Campbell.

Born in Liverpool, Campbell began his career as an HP Lovecraft imitator, but soon began to set his horror stories in a recognizable late ‘70s landscape. His Liverpool and London are necropolises of marginalized people, hateful shut-ins, and gutter-crawling journalists, their loneliness and isolation amplified by the urban hellscapes in which they’re entombed. His characters can’t trust their perceptions, inanimate objects exhibit consciousness, living creatures behave like automatons, and personalities are overwritten and replaced by malignant entities and madness. Often his narrative voice is deeply embedded in the perceptions of characters who are unbalanced, delusional, dreaming, or in altered states:

'The clock was chanting: see you on Jan, see you on Jan. His mind listed places he must wipe, over and over. Had he forgotten one? The door. The doorknob. The table. The chair in which he’d sat. The cup – he must wipe all the cups, to make sure.'

His novels like The Doll Who Ate His Mother (1976), The Face That Must Die (1979) and The Nameless (1981) won awards and readers in the UK and the US, but he never became a household name. Despite publishing an enormous number of novels and short stories he remains a writer’s writer, and the only two movies based on his books were both made for the Spanish market. Guillermo del Toro calls him 'the best contemporary master of horror in the UK' but somehow mainstream recognition continues to elude him, even after fifty years of award-winning tales.

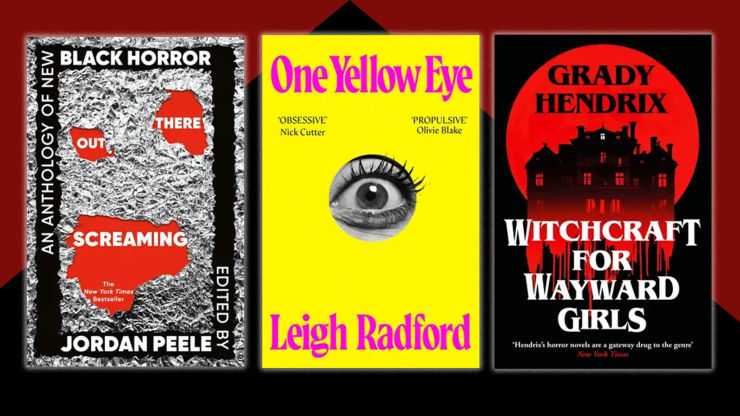

Not so the other torchbearer, Clive Barker, who burst onto the scene in 1984 when his three volumes of short stories, The Books of Blood, came out of nowhere, courtesy of Sphere, and caused a sensation. They were republished as cheap paperbacks in the US where Stephen King established Barker’s bona fides by stating, 'I have seen the future of horror and his name is Clive Barker,' a blurb which was soon plastered across the cover of every Barker book.

An out gay man with roots in Britain’s experimental theater scene, Barker was so completely immersed in the counterculture that he couldn’t see the mainstream anymore. The Britain he grew up in was a place where punk ruled fashion and New Wave ruled the radio. His stories were set in a country that resembled Campbell’s urban hellscape only the hell felt funkier and he brought complete conviction, serious craft, and a forensic eye for grotesque detail to his stories about living cancers hiding out in movie theaters and an army of severed hands declaring war on the human race.

Barker had two thick, well-reviewed bestsellers under his belt (The Damnation Game, 1985; Weaveworld, 1987) when he made his play for the mainstream, writing and directing an adaptation of his own novella, The Hellbound Heart. The movie was renamed Hellraiser and even though Barker had to make trims for the BBFC, this gory gutbuster not only became a hit, but the press loved it (“dazzling” cooed Time Out London), and it established its monster, Pinhead, as a horror icon to rival Jason and Freddy. Even though Barker never had a hit that big again, he moved to Los Angeles and continued to turn out movies, books, and paintings for decades to come.

‘Today, British horror literature is still rowdy and still gory but it’s achieved a respectability that eludes it in the States.’

Today, British horror literature is still rowdy and still gory but it’s achieved a respectability that eludes it in the States. A stage adaptation of Susan’s Hill’s ghost story, The Woman In Black, ran a record-breaking 13,232 performances on the West End, while A-list authors like Hilary Mantel, David Mitchell, and Sarah Waters have all turned out horror novels at some point. In 2023 alone there were five high-profile productions of that witch-infested, gore-encrusted horror show Macbeth, featuring everyone from Ralph Fiennes to Cush Jumbo.

Tourists may think of the UK as the land of Downtown Abbey and afternoon tea, but if you love horror it’ll always be the country that gave the world killer crabs, deranged slashers, and Pinhead.

The 50th anniversary edition of The Rats is out now. Grady Hendrix's new novel, Witchcraft for Wayward Girls is out in January 2025, and available for pre-order.

Witchcraft for Wayward Girls

by Grady Hendrix

‘I did an evil thing to be put in here, and I’m going to have to do an evil thing to get out.’

St. Augustine, Florida. 1970. Fifteen-year-old Fern has just arrived at Wellwood House, a 'home' for unwed mothers. Every second of her and the other teenagers' days is rigidly controlled by adults who claim to know what's best. Then Fern is given a book about witchcraft, and the balance of power suddenly shifts. But such gifts always come with a price. And it's usually paid in blood.

1 Quoted in Hammer Films: The Bray Studios Years by Wayne Kinsey