The best books about the First World War

From moving poetry collections to fascinating first-hand historical accounts, here we share our edit of some of the best books about the First World War.

More than one hundred years have passed since the hostilities of the First World War ceased and the guns fell silent after four long years of devastating conflict.

Literature, whether written by those who were there or by those who wish to pay tribute, has kept the Great War and those who lost their lives throughout it in our collective memory.

Here we've curated our edit of the best books about the Frist World War, from enthralling fiction, to moving poetry collections and unfathomable first-hand historical accounts.

The best non-fiction about the First World War

A World on Edge

by Daniel Schönpflug

A World on Edge reveals Europe in 1918, left in ruins by World War I. With the end of hostilities, a radical new start seems not only possible but essential. Unorthodox ideas light up the age: new politics, new societies, new art and culture, new thinking. The struggle to determine the future has begun. Historian Daniel Schönpflug describes this watershed year as it was experienced on the ground from the vantage points of people who lived through the turmoil – open ended, unfathomable, its outcome unclear.

Forgotten Voices Of The Great War

by Max Arthur

The history of the First World War told through the real-life stories of the people who survived it, in their own words, Forgotten Voices is an important record of the monumental events of 1914 - 1918. Compiled from the Imperial War Museum's aural archive, this is a compelling history of World War One from those that experienced it first hand.

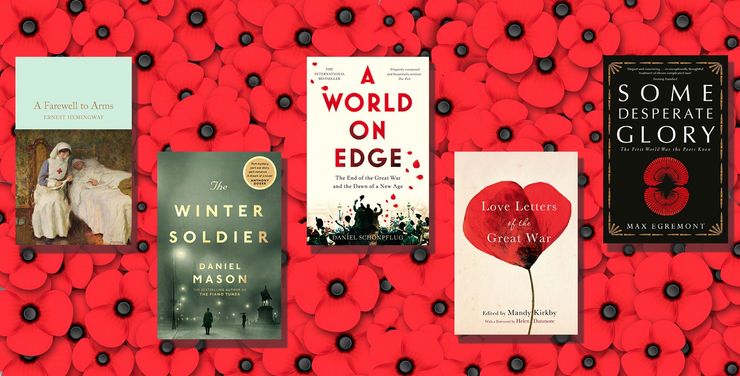

Love Letters of the Great War

by Mandy Kirkby

Many of the letters collected here are eloquent declarations of love and longing; others contain wrenching accounts of fear, jealousy and betrayal; and a number share sweet dreams of home. But in all the correspondence – whether from British, American, French, German, Russian, Australian and Canadian troops in the height of battle, or from the heartbroken wives and sweethearts left behind – there lies a truly human portrait of love and war. These letters offer an intimate glimpse into the hearts of men and women separated by conflict, and show how love can transcend even the bleakest and most devastating of realities.

The World's War: Forgotten Soldiers of Empire

by David Olusoga

In this vital work, historian David Olusoga describes how Europe's Great War became the World's War, and explores the experiences and sacrifices of four million non-European, non-white people whose stories have remained too long in the shadows. A unique account of the millions of colonial troops who fought in the First World War, and why they were later air-brushed out of history, David Olusoga's meticulously researched The World's War is not to be missed.

Defeat at Gallipoli

by Nigel Steel

The battle for Gallipoli has been described as 'one of the world's classic tragedies'. In Defeat at Gallipoli, the participants tell the story of this failed offensive. The bitter campaign against the Turks was ill-conceived, inadequately equipped and never likely to succeed. The bravery of the troops in the face of disease and violent death is shown in their letters, diaries and recorded memories, recalling the sordid reality of the campaign. Linking together these experiences, Nigel Steel and Peter Hart provide a new insight into the lives of the soldiers involved and a powerful, moving account of a doomed campaign.

The Imperial War Museum Book of 1914

by Malcolm Brown

1914: a year shattered by war following a Balkan assassination. Initial excitement fades into grim reality as weeks turn into a protracted conflict. British soldiers encounter desolate refugees, their lives torn apart by battles like Antwerp, Mons and Ypres; even the fragile Christmas Truce, brought home the awful reality of war. Using new letters and diaries from the archives of the Imperial War Museum, Malcolm Brown skillfully recreates this pivotal year through the moving experiences of men and women who felt the war first-hand, vividly capturing the brutal reality of war as well as moments of great humanity.

The best fiction about the First World War

A Farewell to Arms

by Ernest Hemingway

Frederic Henry is an American Lieutenant serving in the ambulance corps of the Italian army during the First World War. While stationed in northern Italy, he falls in love with Catherine Barkley, an English nurse. Theirs is an intense, tender and passionate love affair overshadowed by the war. Ernest Hemingway spares nothing in his denunciation of the horrors of combat, yet vividly depicts the courage shown by so many.

The Winter Soldier

by Daniel Mason

Lucius is a twenty-two-year-old medical student when World War One explodes across Europe. Enraptured by romantic tales of battlefield surgery, he enlists, expecting a position at a well-organized field hospital. But when he arrives, at a commandeered church tucked away high in a remote valley of the Carpathian Mountains, he finds a freezing outpost ravaged by typhus. The other doctors have fled, and only a single, mysterious nurse named Sister Margarete remains.

Birdsong

by Sebastian Faulks

Published to international critical and popular acclaim, this intensely romantic yet stunningly realistic novel spans three generations and the unimaginable gulf between the First World War and the present. It is the story of Stephen Wraysford, a young Englishman who arrives in Amiens in 1910. Over the course of the novel he suffers a series of traumatic experiences, from the clandestine love affair that tears apart the family with whom he lives, to the unprecedented experiences of the war itself.

The World and All That It Holds

by Aleksandar Hemon

In an epic tale spanning continents, The World and All That It Holds presents a love story that conquers the Great War, revolution, and even death. On an ordinary day in 1914, pharmacist Rafael Pinto's life shatters with the arrival of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo, propelling him into the menacing trenches of Galicia. Amid the grim realities of war, Pinto's sole motivation is his relationship with fellow soldier, Osman. Their shared journey takes them from the trenches to perilous adventures involving spies and Bolsheviks, traversing mountains and deserts. Throughout this journey, it's Pinto's love for Osman that will truly survive.

The Regeneration Trilogy

by Pat Barker

1917, Scotland. At Craiglockhart War Hospital in Scotland, army psychiatrist William Rivers treats shell-shocked soldiers before sending them back to the front. In his care are poets Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen, and Billy Prior, who is only able to communicate by means of pencil and paper. Regeneration, The Eye in the Door and The Ghost Road follow the stories of these men until the last months of the war. Widely acclaimed and admired, Pat Barker's Regeneration trilogy paints with moving detail the far-reaching consequences of a conflict which decimated a generation.

Fall of Giants

Praised for its strict adherence to historical fact, Ken Follett’s epic novel follows five families experiencing life before, during and after the war. When Russia convulses in bloody revolution and the Great War unfolds, the five families’ futures are entwined forever, love bringing them closer even as conflict takes them further apart. What seeds will be sown for further tragedy in the twentieth century and what role will each play in what is to come?

The Inheritance of Solomon Farthing

by Mary Paulson-Ellis

Solomon Farthing, an heir hunter, stumbles upon an unclaimed fortune of a deceased old soldier, his only lead being a pawn ticket. On his quest to find a relative for his share of the inheritance, he discovers a history dating back to 1918 involving eleven soldiers left on a French farmhouse at the end of World War I. The Inheritance of Solomon Farthing by Mary Paulson-Ellis intertwines the present-day Edinburgh with harsh war days, unraveling how to settle present debts, past dues must be paid.

The Water Diviner

by Andrew Anastasios

Grieving farmer Joshua Connor from the Mallee in Victoria embarks on a journey to Gallipoli post-Great War to fulfil his late wife's wish: finding and burying their three sons in consecrated ground. Amid clashing cultures and shaken beliefs, he learns that his eldest, Art, might be alive. His trek into perilous Anatolia is marked by one haunting question: If Art lives, why hasn't he returned? Based on first-hand resources, diaries and official records, The Water Diviner, now also a feature film starring Russell Crowe, focuses on the battles of hearts and minds as they try to rebuild their lives after the First World War.

The best poetry about the First World War

Poetry of the First World War

by Marcus Clapham

The major poets are all represented in this beautiful Macmillan Collector’s Library anthology, Poetry of the First World War, alongside many others whose voices are less well known, and their verse is accompanied by contemporary motifs. Whether in the patriotic enthusiasm of Rupert Brooke, the disillusionment of Charles Hamilton Sorley, or the bitter denunciations of Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen, the war produced an astonishing outpouring of powerful poetry.

Some Desperate Glory

by Max Egremont

In Some Desperate Glory, historian and biographer Max Egremont gives us a transfiguring look at the life and work of the poets of World War One. Wilfred Owen with his flaring genius; the intense, compassionate Siegfried Sassoon; the composer Ivor Gurney; Robert Graves who would later spurn his war poems; the nature-loving Edward Thomas; the glamorous Fabian Socialist Rupert Brooke; and the shell-shocked Robert Nichols all fought in the war, and their poetry is a bold act of creativity in the face of unprecedented destruction.

Poems from the First World War

by Gaby Morgan

Including poems from Wilfred Owen, Rupert Brooke, Vera Brittain, Eleanor Farjeon, Siegfried Sassoon and many more, Poems from the First World War is a moving and powerful collection of poems written by soldiers, nurses, mothers, sweethearts and family and friends who experienced WWI from different standpoints. It records the early excitement and patriotism, the bravery, friendship and loyalty of the soldiers, and the heartbreak, disillusionment and regret as the war went on to damage a generation.

Discover more essential reads with our edit of the best books of all time.