Why working-class queer stories are ignored

What happens when tender hearts must find love in hostile places, instead of in the bright lights of big cities? Leah Cowan explores the lack of representation of working-class queer love stories and why this representation is so vital.

Historically, popular novels centring queer love stories have tended to follow the well-heeled escapades of wealthy white men. In the works of Oscar Wilde, E.M Forster and Christopher Isherwood to name just a few, sharp tailoring and fine dining provide the recurrent window-dressing for tales of queer joy, adventure, angst and heartbreak. Meanwhile, the trials and tribulations of working-class queer people have received limited representation and mainstream appreciation in literature. In spite of this, a rising tide of celebrated queer novels spotlighting a breadth of experiences and backgrounds is steadily redressing the imbalance.

‘Books were never seen as ‘for people like us’ because they never contained people like us.’

— Douglas Stuart

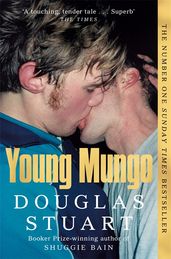

Douglas Stuart’s second novel Young Mungo is one such title, following hot on the heels of his Booker prize-winning debut Shuggie Bain. Both stories chronicle, in different ways, queer boys growing up in poverty in Glasgow in the 1980s and 90s, against the backdrop of Margaret Thatcher’s anti-union policies which decimated Scottish industry and hacked away at working-class solidarity, inflaming a conducive context for violence and homophobia.

Young Mungo depicts the blossoming bond between two young men who fall in love across class and religious divides. Their world is notably small; Mungo’s story is anchored in the four walls of his tenement flat – frequently abandoned by his mother, whose life is equally void of care and support – where he seeks further sanctuary in the close warmth of the boiler cupboard. A second storyline threaded throughout the book moves forward in time to follow a weekend where Mungo is taken to the countryside, but the wide skies and deep lochs are ominous and looming rather than freeing. James, meanwhile, finds solace from the hyper-masculine world around him in the quiet of his doocot, nestled among gently cooing pigeons. Boys such as Mungo and James don’t have the means to escape their environment and find their ‘people’. In the absence of the glittering cafe culture of Paris’ third arrondissement, or the sticky-floored clubs and pubs of London’s Soho they snatch golden hour caresses on slices of grassland framing a motorway overpass.

In this way, the novel invites us to reimagine queer ‘spaces’. Stuart proffers a lover as a safe place of refuge; the gated embrace of tender arms as a temporary barrier against the snarling Orthrus of poverty and toxic masculinity. Young Mungo rebuffs the idea that self-knowledge and exploration as a queer person is a journey only afforded to those wealthy enough to soar above class oppression, which certainly limits movement and access to resources. While Mungo’s terrain is undoubtedly one of danger and violent abuse, he walks a trail that also encompasses moments of sweetness and connection; Stuart’s deftness in moving between these modes of light and shade in the novel makes for a heart-stopping white-knuckle ride.

‘Young Mungo rebuffs the idea that self-knowledge and exploration as a queer person is a journey only afforded to those wealthy enough to soar above class oppression’

Stuart has previously shared that 'books were never seen as ‘for people like us’ because they never contained people like us.' Writers who are marginalised because of their queerness, as well as through experiencing oppression due to race, class, disability and more, have not typically been encouraged (or resourced) to document their stories, nor have they been sought out and championed by the publishing industry.

The effect of this lack of celebrated working-class queer literature is known in sociology as ‘symbolic annihilation'. Quite literally, this describes a sustained attempt to blast away the existence of working-class queer people. This strategic denial of representation upholds the status quo, which tries to suggest that working-class queer people don’t have a role in society, and can be demonised and pushed to the margins.

In complete contrast, Young Mungo joins a modest but robust canon of working-class queer love stories, notably alongside: James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room (1956) which tells the tragic tale of star-crossed romance between Giovanni, an Italian bartender, and his globe-trotting American lover. Leslie Feinberg’s Stone Butch Blues (1993) is also a deeply compelling trans and queer narrative, centring around Jess Goldberg, a gender non-conforming factory worker and union organiser, who faces extreme police brutality, but also depicts their experiences of falling in and out of love. Chinelo Okparanta’s Under the Udala Trees (2015) similarly explores the pain of an abruptly terminated relationship in a context of intense homophobia, following the story of Ijeoma who is sent to work in teacher’s house after the death of her father, where she develops a deep bond with an orphan Amina, against the backdrop of the Biafran war.

‘The narratives of marginalised working-class queer people are not ‘niche’, but part of the rich tapestry of queer experience’

Young Mungo, among other titles, makes it plain that queer working-class love stories most certainly exist and should be celebrated. The narratives of marginalised working-class queer people are not ‘niche’, but part of the rich tapestry of queer experience, which itself is borne out of finding, enjoying and sustaining love and lust in the most unlikely and hostile of places.

Young Mungo

by Douglas Stuart

The extraordinary, powerful second novel from the Booker prize-winning author of Shuggie Bain, Young Mungo is both a vivid portrayal of working-class life and the deeply moving story of the dangerous first love of two young men: Mungo and James. Young Mungo is a gripping and revealing story about the meaning of masculinity, the push and pull of family, the violence faced by so many queer people, and the dangers of loving someone too much.

Giovanni's Room

by James Baldwin

After David, a young American living in 1950s Paris meets the mysterious Giovanni in a bar the two begin an intense affair. When David's girlfriend returns three months later he is forced to choose between them, which has devastating consequences for them all. Highly controversial when it was first published in 1956 for it's portrayal of a gay relationship in mainsteam literature, James Baldwin’s tale of an ill fated love triangle is now considered a classic.

Under the Udala Trees

by Chinelo Okparanta

It's 1968: the height of the Biafran civil war. Ijeoma's father is killed and her world is transformed forever. Separated from her grieving mother, Ijeoma meets another lost young girl, Amina, and the two become inseparable. As their relationship develops, it spn begins to shake the foundations of Ijeoma's faith, test her resolve and flood her heart. In this masterful novel Okparanta takes us from Ijeoma's childhood in war-torn Biafra, through the perils and pleasures of her blossoming sexuality, her wrong turns, and into the everyday sorrows and joys of marriage and motherhood.

Celebrate queer literature, with the best of queer YA fiction.

Background image photo credit: Shingi Rice on Unsplash