Brilliant Christmas gift ideas: the best books to give in 2025

From stocking fillers and Secret Santa ideas to the latest releases for the literature lover in your life, here's our selection of the best books to give as gifts this festive season.

Whoever you're buying for, you can never go wrong with a good book. A thoughtfully chosen novel or non-fiction title can show that you really know a person, while a beautifully bound festive story or poetry collection is a low-risk but appealing option for colleagues or in-laws. Read on for our bookish Christmas gift guide.

If you're shopping for the little bookworm in your life, take a look at our favourite Christmas books for kids.

The best books for your Secret Santa, and stocking filler ideas

Whether you're looking for a safe but interesting alternative to a bottle of wine or box of biscuits, or a small, thoughtful gift for a friend, these books can be carefully matched to the recipient's interests and make great gifts.

The Rest is Quiz

by Goalhanger

Who declared to the House of Commons, ‘The Prime Minister is not under a desk!’? How did Attila the Hun meet his unfortunate end? And who was the first goalkeeper to score in a Premier League match? Perfect for history buffs, politics addicts, sports fanatics and pop culture followers, this quiz book from power podcast producers, Goalhanger, contains over 1,000 diverting questions to keep everyone entertained over the holiday period.

Great for fans of: Pub quizzes, trivia, The Rest Is Politics, The Rest Is History, The Rest Is Football and The Rest Is Entertainment

Killer Puzzles

by Archer Thorne

Put your detective skills to the test! This book contains over 120 challenging puzzles, including crosswords, cryptograms and quizzes, which gradually reveal hundreds of fascinating facts and true crime stories.

Great for fans of: True crime, history, puzzles, detective stories, challenging quizzes

Twas The Nightshift Before Christmas

by Adam Kay

Christmas is coming, the goose is getting fat . . . but 1.4 million NHS staff are heading off to work. In this perfect present for anyone who has ever set foot in a hospital, Adam Kay delves back into his diaries for a hilarious, horrifying and sometimes heartbreaking peek behind the blue curtain at Christmastime. This is a love letter to all those who spend their festive season on the front line, removing babies and baubles from the various places they get stuck, at the most wonderful time of the year.

Great for fans of: This is Going to Hurt, funny books, Bill Bryson, moving stories, real-life

On Your Marks

by Martin Polley

This wide-ranging, entertaining collection of classic sports writing is drawn from journalism, diaries, drama, fiction and more. On Your Marks takes its reader from Elizabethan Shakespeare to twentieth-century George Orwell via Daniel Defoe on horse racing, Jane Austen on baseball, Lewis Carroll on croquet and many more.

Great for fans of: Sport, beautiful books

Jane Austen's Fashion Bible

by Ros Ballaster

Exquisite colour drawings from Regency magazine La Belle Assemblée and their entertaining descriptions are matched with much-loved passages from Jane Austen’s published novels, letters and manuscript fiction. From elaborate evening gowns and elegant walking dresses to charming seaside outfits, this book brings the world of Jane Austen to life.

Great for fans of: Fashion, Jane Austen, Bridgerton, humour, history

One Day One Moment

by Vex King

This six-month daily planner introduces you to the power of mindful planning, every day. Discover effective planning techniques, such as setting a Power Hour, the 50–10 method and time blocking, alongside health trackers, affirmations and mindful activities to help you take care of your well-being. Each month offers the opportunity to answer reflective questions and fill in a work–life balance wheel so you can follow your progress.

Great for fans of: Manifesting, affirmations, mindfulness, journaling, self-care, finding balance

New releases for keen readers

Impress the bookworm in your life with a new release they may not have read yet. For even more inspiration, take a look at our guides to the best fiction, best literary fiction and best non-fiction of 2025.

Girl Dinner

by Olivie Blake

This darkly funny novel about ambition and privilege is the latest must-read from Sunday Times and New York Times bestselling author Olivie Blake. Student Nina Kaur and professor Dr Sloane Hartley both believe they'll find the answer to their problems inside The House, the most exclusive sorority on campus. However, as they're drawn further into the sisterhood’s arcane rituals, they learn that collective perfection comes with bloody costs. . .

Great for fans of: The Lamb by Lucy Rose, Yellowface by R. F. Kuang

The Killing Stones

by Ann Cleeves

When a violent storm descends upon Orkney, the body of Archie Stout is left in its wake. An unusual murder weapon, a Neolithic stone bearing ancient inscriptions, is found discarded nearby. Detective Jimmy Perez, no stranger to the complexity of human nature and the darkness it can harbour, is soon on the scene. He counted Archie as a childhood friend, so this case is more personal than most. Here, in these ancient lands where history runs deep, Perez must discern the truth from legend before a desperate killer strikes again . . .

Great for fans of: Shetland, crime fiction, Ian Rankin, Val McDermid

Red City

by Marie Lu

A compelling mix of magical mob rivalry and star-crossed ambition, all set in an alternate, present-day Los Angeles. Alchemy is the hidden art of transformation, an exclusive power wielded by two rival crime syndicates, who market it to the world’s elite in the form of sand – a drug that enhances those who take it into a more perfect version of themselves. Childhood friends Sam and Ari find themselves on opposite sides of an escalating conflict between the two groups: Sam, desperate to claw her way into Grand Central for a better life, and Ari, a rising Lumines star. As the two alchemists face off against each other, will either of them be able to survive the coming war?

Great for fans of: V. E. Schwab's Shades of Magic series, One for my Enemy by Olivie Blake, fantasy, enemies-to-lovers

More brilliant escapes for fantasy fans

The best new fantasy books to lose yourself in, recommended by the experts

Read moreWhat Have I Done?

by Ben Elton

Ben Elton has done everything and worked with everybody. Now, in this frank, forthright, and hugely entertaining book, he tells the whole story. From his pioneering stand-up in the eighties to writing iconic hits like Blackadder and The Young Ones, alongside his life off-stage and screen, Ben talks honestly about his relationships with brilliant friends, inspiring contemporaries, and occasional foes. Plus, of course, a ‘little bit of politics’.

Great for fans of: British comedy, Blackadder, The Young Ones, Upstart Crow, inside stories, celebrities

Simply More

by Cynthia Erivo

The acclaimed actor reflects on her personal growth and the powerful lessons she has learned both on stage and in life. Cynthia Erivo uses personal vignettes and her experiences running marathons, real and metaphorical, to demonstrate that it is never too late to build the life you are seeking.

Great for fans of: Wicked, inspirational stories, film, theatre

Always Home, Always Homesick

by Hannah Kent

In an exquisite love letter to Iceland, Hannah Kent reflects on her life-changing experience as a seventeen-year-old exchange student from Australia, and the creative process behind her celebrated novel Burial Rites. When she first arrived in Iceland, the author had never seen snow before. Living through a dark winter in a remote part of the country, she found herself in love with the island, in a way that remains strong twenty years later.

Great for fans of: Burial Rites, historical fiction, literary memoirs, travel writing

Ride with Me

by Simone Soltani

Stella Baldwin’s world has recently fallen apart. Left at the altar and humiliated online, she’s trying to piece her life back together. Meanwhile, Formula 1 driver Thomas Maxwell-Brown is struggling with career pressure and his newfound reputation as the most hated man on the grid. When their paths cross in Las Vegas, a spontaneous marriage of convenience seems like the perfect solution. But as they navigate their new reality, sparks fly, and the line between convenience and something deeper begins to blur.

Great for fans of: Romance, slow-burn, Cross the Line by Simone Soltani, Drive to Survive

The Discovery of Britain

by Graham Robb

Graham Robb presents a history of Britain unlike any other. The prize-winning author takes us on a time-travelling adventure across the country, often from the unique vantage point of his bicycle. This is not a conventional history, but a blend of personal observation, geography, and historical research that redefines our understanding of the nation. Encounter an entertaining cast of characters foreign and homegrown, drop in on places and events, and dwell on the successes and catastrophes across British history. Perfect for readers who want a history book that is both erudite and engaging.

Great for fans of: British history, cycling, maps

Beautiful editions and coffee table books

Dear New York

by Brandon Stanton

A love letter to the streets, stories, and souls that define NYC and its people. This beautiful book includes nearly five hundred full-colour pages of portraits and stories from every corner of the city. With more than seventy-five percent of the photographs and stories in Dear New York never having been published before, there’s a new discovery on every page.

Great for fans of: American culture, Humans of New York, photography, human stories

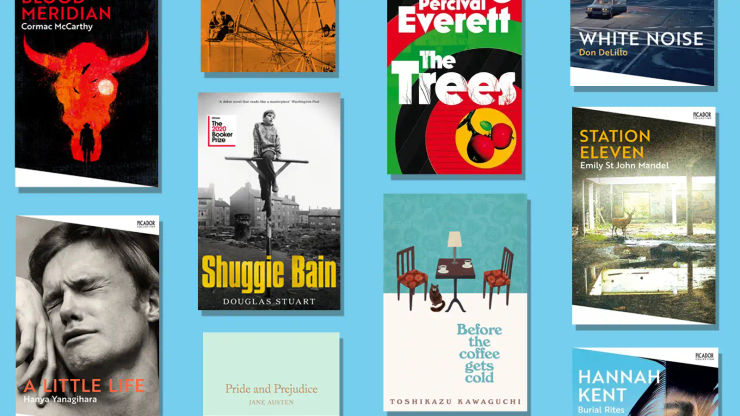

A Little Life

by Hanya Yanagihara

The special anniversary edition of A Little Life features artwork by acclaimed artists RF. Alvarez and Linus Borgo, painted in response to the book, and a Q&A with Hanya Yanagihara. A perfect gift for existing fans and new readers alike. JB, Jude, Malcolm and Willem. Four young men move to New York broke, adrift and buoyed only by friendship and ambition. There is kind, handsome Willem; the sardonic painter JB; Malcolm, a frustrated architect; and Jude, brilliant and enigmatic – their centre of gravity.

Great for fans of: Heartbreak, tales of friendship, literary fiction

Radical Cartography

by William Rankin

A stunning, thought-provoking exploration of how maps shape our understanding of the world - featuring over 150 beautiful full-colour maps. Maps are everywhere. They can change how cities are designed and how rivers flow, how wars are fought and how land claims are settled, how children learn about race and how colonialism becomes a habit of mind. Maps don’t just show us information – they help construct our world. Cartographer and historian William Rankin argues that it’s time to reimagine what a map can be and how it can be used.

Great for fans of: Cartography, graphic design, geography, politics

Cooking With Vegetables

by Jesse Jenkins

This cookbook, from Instagram star @adip_food, is both a stunning object and full of delicious, veg-based recipes. Distinctive, uncomplicated dishes start with a humble ingredient – such as a carrot, cabbage, leek, tomato - and end up with a delicious meal, in over 100 inventive recipes.

Great for fans of: Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat by Samin Nosrat, Anna Jones, Ottolenghi

Shot Ready

by Stephen Curry

In his own words, NBA Champion Stephen Curry shares his transformative philosophy of success. Centered on intentional preparation, constant improvement, creativity, connection, mindfulness, and joy – drawn from the most important and revealing moments of his life’s journey and delivered in his incomparable voice and style. Shot Ready is beautifully designed with over 100 stunning photographs, the vast majority of which have never been seen before. A rare look into the mindset of a champion, it is a masterclass in unlocking your potential, straight from the greatest shooter of all time.

Great for fans of: Basketball, photography, inspirational stories and advice

A Sound So Very Loud

by Ted Kessler

The definitive book on Oasis. Written by two music journalists who were there from the start, A Sound So Very Loud tells the story of the band through their music. From the early days playing tiny venues to becoming one of the biggest bands in the world, this book unpicks the lyrics, the recordings, and the chaos that surrounded it all. Expect never-before-heard anecdotes, deep dives into the songs, and the kind of outrageous stories only Oasis could generate. Essential reading for any fan.

Great for fans of: Oasis, Britpop, '90s nostalgia, behind the scenes, songwriting

Reading recommendations sure to strike a chord with Oasis fans

What’s the story? Books to read if you love Oasis

Read moreFestive reads

Classic Christmas Crime Stories

by David Stuart Davies

Christmas is not always the season of goodwill. As this hugely entertaining collection shows, it can also be the season of mysterious deaths, hidden poison bottles and blunt instruments. This collection of eleven stories from the Golden Age of British crime writing features festive whodunnits by Margery Allingham and Ngaio Marsh. There are unexplained deaths by all manner of suspects and dastardly Christmas crimes to be solved. Each story is brilliantly plotted – some deliciously tense, others laced with humour – and each is bound to thoroughly entertain.

Great for fans of: Cosy crime, Agatha Christie, whodunnits

A Christmas Ghost Story

by Carol Ann Duffy

It’s Christmas Eve in London’s financial district. A billionaire in his penthouse suite is visited by the ghost of Sarah Whitehead, the grief-stricken nun who has haunted the Bank of England for hundreds of years. What follows is a spellbinding journey through the night and around the globe as the ghost shows the billionaire the human suffering on which his excessive wealth depends. A gorgeously illustrated tale for our times with all the magic of Dickens, reminding us that love is the greatest treasure of all.

Great for fans of: Poetry, A Christmas Carol

All I Want for Christmas

by Karen Swan

Darcy Cotterell isn’t feeling particularly festive. Newly single, again, she's not even going home for Christmas. Instead she will be spending her holiday finishing her art history PhD. When her best friend, Freja, signs Darcy up to a dating app, she agrees to three dates – but her mind is on work, not play: an unknown portrait by Denmark’s greatest painter has been found and she is tasked with identifying the woman in the painting. During her research, she encounters sexy, arrogant lawyer Max Lorensen – who happens to be bachelor number one! The attraction is instant but, knowing they must work together, they abandon the match. Or try to. But their feelings are undeniable – until Darcy discovers Max has an agenda . . .

Great for fans of: Romance, cosy reads, art history

The Cat and the Christmas Kidnapper

by L T Shearer

Join Lulu Lewis, a retired detective with a knack for uncovering secrets, and Conrad, her extraordinary talking cat, as Christmas cheer gives way to festive fear. Hoping for a relaxing festive break, Lulu sets off with Conrad on her canal boat, The Lark, to the picturesque city of Bath to visit friends. But when the pair arrive, they learn of a ruthless kidnapping plot that is plaguing parents in the area. As the kidnappers fuel panic with further demands, the pair must unravel clues faster than Conrad can charm with his witty banter. That is, if they are to stand any chance of bringing the criminals to justice in time to save the holidays.

Great for fans of: Richard Osman and S. J. Bennett

Classic books to give as gifts

A Christmas Carol

by Charles Dickens

First published in 1843, Charles Dickens' classic Christmas novella was an overnight success. It is the tale of miserly Mr Scrooge who – through a series of eerie, life-changing visits from supernatural companions – begins to see the error of his cold-hearted ways one fateful Christmas Eve. With heart-rending characters, rich imagery and evocative language, the hopeful message of A Christmas Carol remains as significant today as when it was first published.

Great for fans of: A traditional Christmas, ghost stories, heart-warming tales

Find the perfect Dickensian gift

11 of the best Charles Dickens books (for every type of reader)

Read moreClassic Love Stories

by Becky Brown

Show your love this Christmas with this meticulously chosen collection of stories about love in all its guises. O. Henry brings comedy with his tale of a busy broker working too hard to remember that he’s actually married his adored young wife. There’s Anton Chekhov’s famous story about true love and devotion, The Lady with the Dog and Katherine Mansfield writes touchingly about unrequited love in Mr. and Mrs. Dove. With stories spanning first love to enduring love in old age, from infatuation to heartbreak told by some of the best writers, Classic Love Stories makes a perfect gift.

Great for fans of: Romance, love stories

Classic Fantasy Stories

by Farah Mendlesohn

From the eerie to the magical by way of the deeply strange, this collection of short stories is a the perfect present for all fantasy fans. Oscar Wilde’s The Happy Prince draws on the great fairy tale tradition. Elizabeth Gaskell’s The Old Nurse gives us a taste of the Gothic whilst H.P. Blavatsky journeys into the weird. The effects of war and loss are keenly felt by Arthur Machen in his moving story The Bowmen. And in Victorian times, children’s writers such as Edith Nesbit spin the most charming fantastical tales in stories like The Dragon Tamers. These amazing feats of imagination brilliantly showcase the many facets of fantasy writing.

Great for fans of: Fantasy, fairy tales, short stories