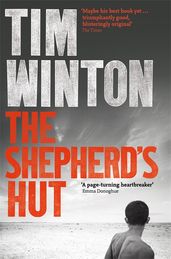

Tim Winton on his inspiration for The Shepherd's Hut

'He showed up unannounced, uninvited and damn-near unmanageable from the get-go. I mean, who’d choose to write a novel from the point of view of a feral ratbag like Jaxie? He’s a handful on a good day.'

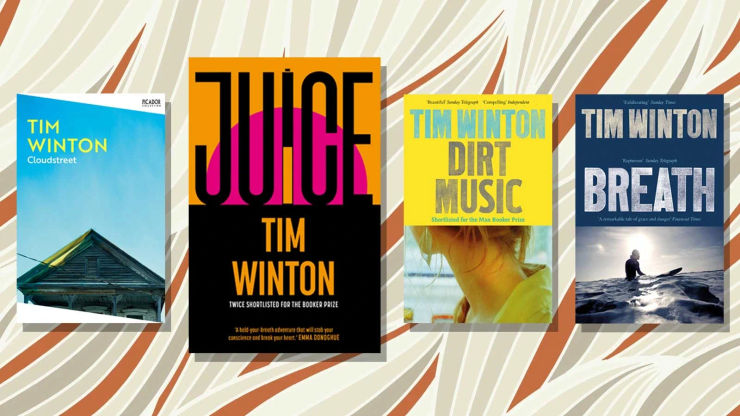

Tim Winton is the award-winning Australian author who has twice been shortlisted for the Booker Prize. His novel Breath was adapted into a film directed by and starring Simon Baker and an adaptation of his novel Dirt Music is currently in production. Here Picador editor Sophie Jonathan introduces Tim Winton's twelfth novel, The Shepherd's Hut, and discusses the characters and landscapes of the novel with the author.

The Shepherd’s Hut is a visceral coming-of-age story and a passionate drama of love set in a vast and dangerous landscape - I’ve not read a novel that has gripped me like this for years.

The novel tells the story of Jaxie, who lives alone with his abusive, drunken father. That is until the day Jaxie returns home to discover his father’s body. He must escape his town and the accusations of murder that will fall on him, so he sets off into the bush on foot. He will hide out until he is sure he isn’t being followed, avoiding the highway, surviving on the animals he shoots. Eventually Jaxie comes across a solitary camp. Its sole resident, ex-priest Fintan MacGillis, has been there for eight years, visited only every six months by someone who brings him supplies. Fintan’s life of isolation is both escape from a terrible crime and exile, his punishment that he will never have the opportunity to confess. Drawn together by an agreement that neither will speak about their past, Jaxie and Fintan form a bond, and Jaxie finds himself forced to grow from a child to a man in order to protect someone more vulnerable.

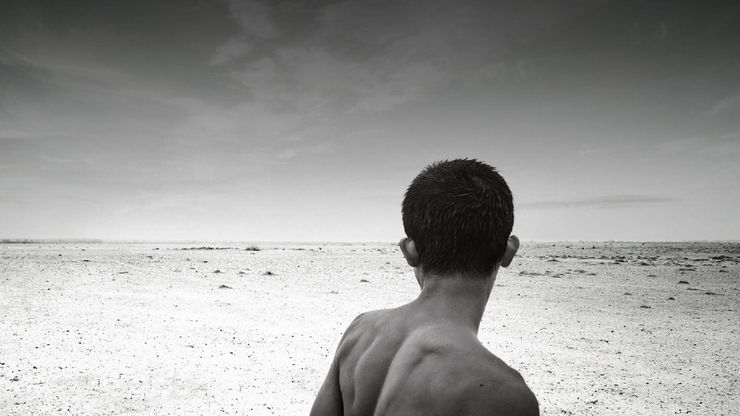

The Shepherd's Hut is a book of elemental, hypnotic beauty. Reading it is a sometimes breathless experience, but this is also a novel whose energy and sadness linger long in the mind. Like all of Tim’s novels, The Shepherd’s Hut is a book of huge heart and compassion, and in Jaxie Tim has created such a vivid, vigorous character. Jaxie feels like one of the great narrative creations; the rough swing and pull of his voice gets under your skin like nothing else – reading this I feel as abandoned, as in danger, as set free as he does. And, of course, no one writes landscape like Tim Winton. The landscape of The Shepherd’s Hut tricks the eye, provides safe haven or harbours criminals, and threatens to kill those who haven’t reckoned with its hot, waterless emptiness.

SJ: The Shepherd’s Hut is written from the point of view of a teenager – Jaxie Clackton. Why did you want to write the voice of a boy on the cusp of adulthood?

TW: Well, to be perfectly frank, I didn’t exactly choose to do it this way. To some extent the voice chose itself. Jaxie’s sound arrived with the imagery, with the scenes I began to see when this story turned up. I was writing something else at the time, so his advent was inconvenient. To that extent Jaxie has always been consistent, I’ll grant the little bugger that much. He showed up unannounced, uninvited and damn-near unmanageable from the get-go. I mean, who’d choose to write a novel from the point of view of a feral ratbag like Jaxie? He’s a handful on a good day. And there were some days I wondered if I could stand another moment of him. I certainly wondered if a reader would come at him for more than a few pages. But readers have told me Jaxie endears himself somehow. They don’t know whether to wring his neck or hug him and give him a feed. Which makes me wonder if I wasn’t under-estimating the character, and the reader as well. And that’s a lesson for me, even this late in the caper. After nearly 40 years of doing this for a living I clearly still need reminding how unlikely art and literature are. Art is confounding, isn’t it? A work of art is something that lives and works against all odds, something that shouldn’t work is there in front of you, alive and afoot, somehow more than the sum of its unlovely parts.

SJ: Fintan, the ex-priest that Jaxie discovers living alone in a shepherd’s hut is – like Jaxie – in a sort of exile. Why did you choose this encounter, and what do Jaxie and Fintan have to offer each other?

TW: Again, I think you’re assuming I knew what I was doing! Not that I’m complaining; it’s flattering to be over-estimated like this. But the fact is, I went on the trek with Jaxie with even less of a plan than he has when he sets out. In a sense you could say I wrote it to find out what happens and who’s out there in the salt country Jaxie’s travelling through. Now, of course, I see why it makes sense to have him meet Fintan and why the old man is who he is. Jaxie’s from a really tough background. In his world, men don’t say much; they let their hands – often their fists – do the talking. There’s a real wariness about introspection, a fear of uttering, a poverty of expression. Jaxie’s 15 or so, and school has been a disaster. He’s largely uneducated. And it was strange and interesting to have him bump up against someone from a radically different world. Socially as much as geographically. Fintan is educated, for one thing. And he has language and music – all very confounding for Jaxie. Fintan hasn’t chosen to be out there in the wilderness. Exile has been imposed upon him. So, in a sense, he and the boy are polar opposites. The old man consigned to solitude, waiting for the end of days, and the kid who’s fled the familiar world and gone in search of some shred of hope to hold to for the future.

These two need each other, even if it takes them a while to understand this. Each is an unlikely mentor and goad to the other. In a way, the landscape imposes the relationship upon them. Australia is not a continent for the Romantic solitary. In order to survive beyond the scrim of settlement, you need company – alliances, co-operative relationships. Nature imposes strict terms on culture. People have survived here for 60,000 years and for the bulk of that time they survived because they lived and travelled in groups. The sophistication of their relationships – to one another, to the clan, to the natural world – was the key to their success. Like most of modern Australia, like much of the developed world, Jaxie and Fintan are copping on to this a bit late in the piece. I mean, here are two blokes with very scanty notions about relationships having to cooperate and let there other in.

SJ: Where did the idea for The Shepherd’s Hut come from?

TW: I have no idea where this book came from. It began with that grisly scene in the shed where Jaxie comes upon his father crushed beneath the vehicle that’s fallen off the jack. I had no idea what that was about, to be honest. Looking back, I imagine it’s come from years of living in remote country places, hypermasculine places, watching men and boys existing in a very thin and acrid atmosphere that stunts them and makes women miserable, fearful or just resigned. I’ve seen a lot of boys possessed of strong feelings who lack a means of expression – and I suppose I mean a safe means of expression – for those intense emotions. There seems to be a correlation between violence and poverty of expression.

I guess I was interested by Jaxie because he has some native intelligence, a yearning for ideas, an urge to reach for something richer, better, but he lacks a language and perhaps more importantly, a social licence with which to explore that. To that extent, he’s trapped in the world he’s from, socially. I come from a working class background, and although I’ve had the benefit of some education I still live around people who lack the kind of mobility and safety that language can offer. I’m interested in those constraints, the intensity of people’s feelings. I’ve tried to write about that. And because I love demotic expression, I enjoy the challenge of rendering lumpy vernacular talk in ways that acknowledge the unlikely beauty in it.

SJ: The Australian landscape is very important in all of your novels, but people more often associate you with the sea. Why did you set The Shepherd’s Hut in the saltlands of Western Australia? And what is special about the Australian landscape?

TW: Yeah, landscape is central. And by that, I mean the natural world. Yes, people do associate me with the sea, even though I’ve written quite a bit about people and places away from it. But I’m an islander, Australians are islanders, let’s not forget. So even if we’re not on the shore or dealing with the sea, the ocean is ever-present, even it’s expressed as an absence. And I’ve written before about how oceanic the desert is.

There’s this tendency in ‘developed’ societies, and certainly in their art, to treat landscape as mere backdrop, as wallpaper, really, just a few flat details in the background. And I guess over the years I’ve been writing it as foreground, as the terms of trade for whatever happens in my story. Because the characters and their problems spring from their place. That’s how I see it. I’m responding to the ecological logic underpinning everything. People are acting in the natural world, and as we now know at our end of history, we’re certainly acting upon the natural world (just ask the weather folks) but we forget the degree to which we are acted upon – that is to say, shaped – by the natural world. I suspect that’s a little more apparent in Australia than it is in the UK. Though I think you can read it in a Brit’s posture now and then, especially in the street around a Tube station at 8am. Is it just me imagining this, or is there a special hunch the English commuter has when upright and ambulatory? That under-the-brolly-head-down-between-the-shoulders posture that suggests the low, grey sky is heavier than taxation and Brexit. There are people like Jaxie in the UK, don’t get me wrong. But their stories will play out on different terms because of place. Place and language.

As to why I set this book in the salt lands, I don’t know how to answer except to say that I like strong places. I travelled and camped a fair bit in the northern goldfields of Western Australia. Places get under my skin, I guess. And if you look at a place long enough, even a place that appears empty or lacking in activity, eventually something happens, someone emerges. I sit still – out there, or at the desk back home – and wait until something shows up. Eventually something bubbles up out of the salt crust, or the gibber plain, or the shorebreak. At least, that’s how it’s worked until now. But I guess nothing’s forever.

SJ: And finally . . . what are you reading and enjoying at the moment?

TW: I just read Tara Westover’s Educated with a mixture of horror and admiration. Anyone who’s ever had a taste of a closed culture or a slightly nutty family will wince more than once in recognition. And I liked The Water Will Come by Jeff Goodell. It’s a pretty cold-eyed look at how cities will be remade by our changing climate. But the most impressive thing I’ve read lately is Richard Powers’ magisterial novel The Overstory. The ambition and scope of the thing is breathtaking. So many novels are just obsessed with manners and mirrors, and here’s someone writing about life itself. What a breath of fresh air – in the form of photosynthesis – that book has been.

The Shepherd's Hut

by Tim Winton

For years Jaxie Clackton has dreaded going home. His beloved mum is dead, and he wishes his dad was too, until one terrible moment leaves his life stripped to nothing. No one ever told Jaxie Clackton to be careful what he wishes for.

And so Jaxie runs. There’s just one person in the world who understands him, but to reach her he’ll have to cross the vast saltlands of Western Australia. It is a place that harbours criminals and threatens to kill those who haven’t reckoned with its hot, waterless vastness. This is a journey only a dreamer – or a fugitive – would attempt.