The secrets behind London's buildings

Rowan Moore, architecture critic for The Observer and author of Slow Burn City, explains some of the stories behind the buildings of our capital city.

Rowan Moore, the architecture critic for The Observer and author of Slow Burn City, explains the stories behind some of the capital's most recognisable locations.

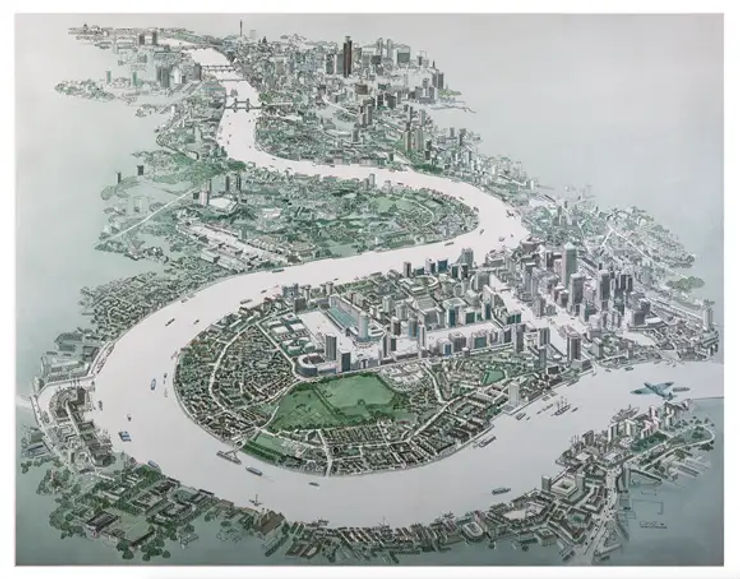

Canary Wharf

Usually visions of the future over-predict, but not Canary Wharf in the Year 2025, drawn by Carlos Diniz to promote the development in 1988. In 2016 there are already more towers than he shows. Also note the Spitfire, presumably included to allay British anxieties about invasion by foreign speculators.

Bevin Court

Bevin Court - or Lenin Court as it was going to be called before relations with the Soviet Union cooled - brings to life the idea of its architect Berthold Lubetkin that 'nothing is too good for ordinary people'.

At it's centre is a dynamic communal stair, whose geometric ballet if circles and triangles recalls the constructivism of revolutionary Russia, where Lubetkin spent his formative years.

The Aviary, London Zoo

A work of tetrahedral Gothic, a folly in the tradition of the English picturesque, a wonder of tensile engineering in which everything seems to hang from everything else.

Inside, the building disappears, leaving you with exotic birds and a slice of the landscape. The aviary, completed in 1965, is the most successful of London Zoo's experiments with radical architecture.

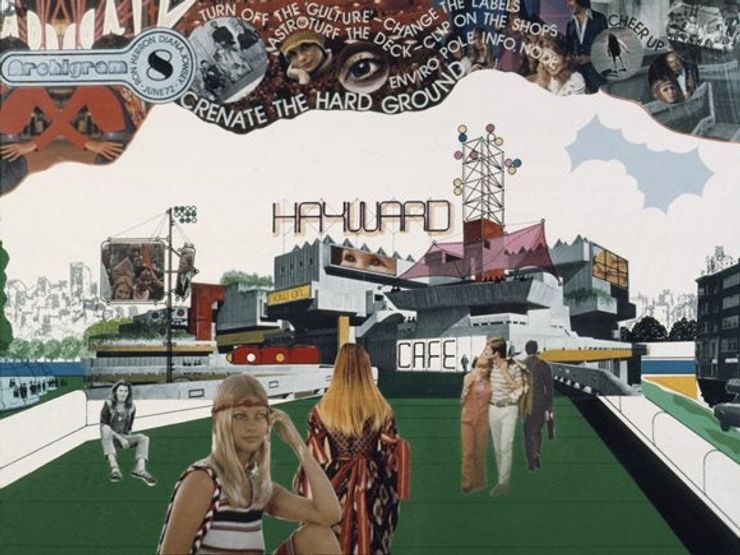

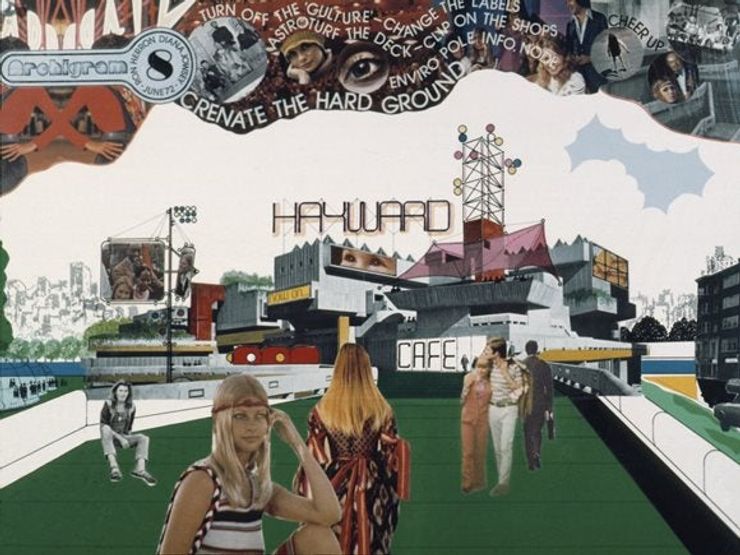

The Southbank Centre

This is how, in 1972, Ron Herron thought the concrete terraces of the South Bank arts centre should be inhabited: with colour, blondes, tents, TV screens and signs. Herron was part of the avant-garde architectural group Archigram, some of whose members had helped design the South Bank. They were in turn building on the Victorian legacy of Joseph Bazalgette, whose embankment of the Thames changed London's relationship to the river.

Walters Way

Everyone who knows Walters Way in south London thinks that it is a wonderful idea: here the architect Walter Segal realised his concept of designing homes such that people could build themsleves houses using standard elements from builder's merchants. Politicians of left and right have been praising and promising self-build housing ever since. But they haven't taken the crucial step of designating land on which it could happen.

Tower Bridge

The 'wilding' movement of the 1970s and 80s was a triumph of popular action, which led to the preservation and enhancement of wild landscapes on wastelands and industrial sites. One (temporary) success was William Curtis Park, a wilderness next to Tower Bridge, which lasted until 1985. Others have become permanent

London Fashion Week

London daily nightly and nightly strives to de-jade the appetites of its inhabitants. In the early hours of a September morning, these skinny white painted riders guarded the entrance to a concrete car park, on whose misty decks were half-naked barmen and trans women strutting in beams of light. It was a party for Fashion Week.

Olympic Zone, Stratford

The Shoal, in the Olympic zone of Stratford, is a desperate attempt to conceal failures of town planning with brightly coloured shapes and epic mixing if metaphors. It is described as fish, leaves, a palisade, a veil, an anchor. But in the end, only draws attention to the disasters it was meant to hide.

Slow Burn City

by Rowan Moore

Rowan Moore's fascinating exploration of the physical fabric of London, Slow Burn City: London in the Twenty-First Century is out now. In his thought-provoking and often uncomfortably funny new book, Moore makes a passionate case for London to invent new ways to respond to the pressures the city currently faces.