How social media is fuelling the rise of the radical right

Recent discourse has seen social media derided as an affront to democracy, but does it really have a malign influence on British politics? Will Cracknell explores the influence of social media in the UK.

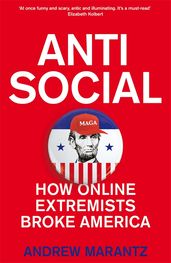

For those of us online, social media influences every area of our lives – what we watch, how we eat, where we go on holiday . . . who we vote for? Andrew Marantz’s book Antisocial examines the growth of the alt-right in America and the ways in which social media has accelerated this rise, but is this a universal phenomenon or a uniquely American problem? Here, Will Cracknell investigates how social media has helped to legitimise and popularise far-right views in the UK.

“Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world”

The Second Coming, William Butler Yeats

The radical right is resurgent. Across the globe, previously sacrosanct boundaries for acceptable political discourse have been desecrated. Politicians from the UK, the US, Brazil and Hungary have ridden waves of populist support to power and are endorsed by contemporary far-right organisations. The sharp distinction between centre-right and far-right – so pronounced in the 1970s and ‘80s – is now murky.

This issue was disturbingly brought into focus in February 2020 when a far-right extremist murdered nine people - predominantly of Turkish heritage - in Hanau, west Germany. The gunman had posted a dossier on his personal website which declared German citizens originating from certain African, Asian and Middle Eastern countries should be “completely annihilated.”

In Britain, the prime minister holds the support of extremists like Britain First and Tommy Robinson. The Home Office faces increasing levels of right-wing extremism, dealing with 1,312 cases in 2017-18 compared to 968 in 2016-17. Across the Atlantic, there were more murders in the US in 2018 by right-wing extremists than in any year since 1995, when Timothy McVeigh bombed an Oklahoma federal building killing 168 people. The previous year, the leader of the free world described a white-supremacist rally in Charlottesville as containing “fine people.”

We can begin to understand this far-right phenomenon through examining the exploitation of social media – including platforms such as YouTube – by radicals who portray unchallenged false narratives as real life. It is curious that when discussing Islamist fundamentalist terrorism, it is often demanded that hate-preachers responsible for radicalisation in mosques or on the internet be condemned, identified and held to account – “Where are the community leaders?” you will have seen breakfast TV presenters ask.

Yet a similar conversation about far-right terrorism has so far been ineffectively explored. In Antisocial: How Online Extremists Broke America Andrew Marantz attempts to do just that. He explains how social media was used by the US alt-right to spread their agenda, how disrupters aimed to topple gatekeepers in dozens of industries including advertising, publishing, political consulting and journalism and how – within a decade – they succeeded beyond anyone’s expectations.

In Antisocial’s prologue, Marantz recalls one interview with an alt-right individual wearing a ‘Harambe’ t-shirt, the gorilla whose killing at Cincinnati Zoo in 2016 sparked genuine internet outrage, then satirical internet outrage, followed by meta-commentaries on the phenomenon of internet outrage. Asked to explain his t-shirt, the wearer answered: “It’s like – it’s just a thing on the internet,” forgetting Harambe was a real animal before an internet meme. For Marantz, this interaction captured how, when experienced through a screen, anything – dead gorillas, gas chambers, presidential elections, moral principles – can start to seem like just another thing on the internet.

But what about the UK? For a long time, conventional wisdom held that the rotten tree of far-right thought would be ill-equipped to take root in the infertile soil of Britain’s democracy. Terrorism was viewed as an issue solely concerning Islamist extremism. Now, however, that characterisation of far-right extremism as a distant, alien affair seems increasingly troublesome. Recent research by anti-terrorism strategy Prevent found a 36% increase in cases of far-right extremists referred for ‘deradicalisation’ programmes. Britain’s most senior counterterrorism officer Neil Basu described the far-right terror threat as “small, but my fastest-growing problem.” In September 2019, Labour MP Dawn Butler pledged that in government her party would commission an independent review into how to combat far-right extremism. And lest we forget the murder of her former colleague Jo Cox by a far-right terrorist who in court stated his name was “death to traitors, freedom for Britain.”

The theme of treachery runs through the far-right’s rhetoric like a leaky tap. While some of those drawn to the isolationist, anti-immigration views of those such as Tommy Robinson may well identify as far-right – or fascist – the majority are better defined by Cas Mudde’s definition of populism: “an ideology that considers society to be separated into two antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite’, and which argues politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people.”

Understanding this division between ‘pure people’ and the ‘corrupt elite’ in the chaotic psyche of the British right-wing populist helps explain why challengers to their view on any matter – be it immigration or Robinson’s prison sentence – are labelled ‘traitors’. They are perceived to be defying that nebulous slogan which consumed post-referendum debate – ‘the will of the people’.

Add this primal sense of betrayal to social media accounts and online personalities adept at reaching large numbers of impressionable people and you’re left with a British breeding ground for far-right radicalisation. One might imagine discussions of far-right extremism to be difficult to access, locked away in a confined corner of the internet.

But according to a report from Data & Society, there is “an alternative influence network” of well-resourced individuals – easily found on Youtube and other platforms – presenting themselves as “an underdog alternative to the mainstream media.” Rebecca Lewis, the report’s author, explained how the unchallenged airing of openly racist ideas on these channels – such as Dave Rubin hosting Canadian right-wing influencer Stefan Molyneux, who openly promotes scientific racism – provides both far-right ideology with a free platform and a theoretical justification for individuals experiencing this visceral sense of betrayal.

Moreover, the lack of official UK far-right leaders forces extremists to look to these social media figures and ‘alternative media’ for direction. While Robinson to some degree retains iconic status, he has yet to adopt any formal position in the current movement or attempted to assemble a leadership team. Perhaps the British far-right’s hostility towards elites can explain this reluctance to establish hierarchical structures. Moreover, maybe this lack of visible leaders detached from the established political system is further evidence of the blurring of divisions between centre and far-right. As poet William Butler Yeats prophesised in The Second Coming: the centre cannot hold. Shifts in political discourse have left far-right extremism more emboldened, legitimised and – most worryingly - mainstream than ever.

Antisocial

For several years Andrew Marantz immersed himself in the world of America’s alt-right, who have so successfully used social media to advance their agenda, as well as spending time with the social media entrepreneurs whose ambition and reluctance to police their platforms allowed this to happen. Antisocial is about how the extreme became mainstream, how the truth became ‘fake news’ and how the unthinkable becomes thinkable, and then becomes reality.