Synopsis

Shortlisted for the Edward Stanford Travel Memoir of the Year Award

'Extraordinary' Daily Telegraph

'Breathtaking' Guardian

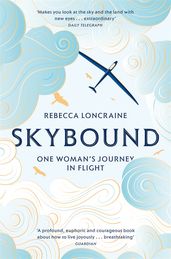

Skybound by Rebecca Loncraine is a book for anyone who has looked up and longed to take flight.

The day she flew in a glider for the first time, Rebecca Loncraine fell in love. Months of gruelling treatment for cancer meant she had lost touch with the world around her, but in that engineless plane, soaring 3,000 feet over the landscape of her childhood, with only the rising thermals to take her higher and the birds to lead the way, she felt ready to face life again.

And so Rebecca flew, travelling from her home in the Black Mountains of Wales to New Zealand’s Southern Alps and the Nepalese Himalayas as she chased her new-found passion: her need to soar with the birds. She would push herself to the boundary of her own fear, and learn to live with joy and hope once more.

Details

Reviews

Profound, euphoric and courageous . . . breathtaking . . . a shimmering parting gift to those still earthbound

A soaring gift of a book. A moving meditation on landscapes and the leaving of them, the freedom of travelling beyond our fears

Makes you look at the sky and the land with new eyes . . . extraordinary . . . a celebration of wind and wings

Stunning . . . Skybound is so full of life - a love letter to nature and a hymn of love to the parental bond