Salman Rushdie on the importance of Muhammad Ali

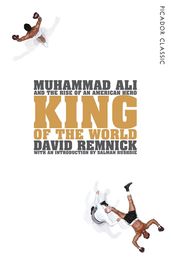

Salman Rushdie on the 'good-looking young boxer with the big loud mouth', from his introduction to the Picador Classic edition of David Remnick's classic biography of America's most dynamic modern hero, King of the World.

Salman Rushdie on the cultural significance of the 'good-looking young boxer with the big loud mouth'.

Taken from Rushdie's introduction to the Picador Classic edition of David Remnick's classic biography of America's most dynamic modern hero, King of the World.

Until Ali came along I had never been interested in boxing. I was familiar with a few names, Louis, Dempsey, Floyd Patterson, Ingemar Johansson – but I didn’t really care about the fight game.

In Bombay, we preferred to watch wrestling, and the great wrestler Dara Singh had been my kind of hero. Just once, at school in Bombay, I had been forced into a boxing ring, terrified. I whispered to my opponent, ‘If you go easy on me I won’t try to hit you,’ and he nodded, okay. Then by pure accident in the first minute of the fight, I bopped him on the nose and he came after me with murderous intent. I never made the mistake of climbing into any ring again.

However, for young fellows of my time – I was sixteen at the time of the JFK assassination, still sixteen when, three months later, twenty-two-year-old Cassius Clay improbably defeated Sonny Liston to win the world heavyweight title, not only defeated him but humiliated him – this good-looking young boxer with the big loud mouth – the Louisville Lip, Cass the Gas – was a joy and an enchantment. And when he took his stand on the draft, refusing to go to ’Nam, sacrificing his title, risking jail, putting it all on the line for a principle, he became, well, awesome. In those days the word still meant what it was supposed to mean, ‘inspiring great admiration/awe’, and Ali did that.

‘One-two-three what are we fightin’ for,’ we sang with Country Joe and the Fish, and Ali the fighter achieved, by refusing to fight, a heroism he could never have attained in the ring, even if he was, as he said he was, The Greatest.

‘The Sixties’ were full of foolishness. The drugs were stupid and the hare-krishna wisdom-of-the-East nonsense was stupid and the Vietnam War was the most stupid thing of all. But in amongst all the stupidity was courage that changed the world, feminist courage, the courage of the civil rights movement, and the courage of Muhammad Ali. The lesson we learned from ‘the Sixties’, if we weren’t too stoned to learn it, was that, it was possible, by one’s own personal, direct actions, to bend the universe to your will, and remake society, improve it, give it better music, higher ideals, and freedom. And Ali was a big part of all of that.

As David Remnick tells us in this extraordinary book, a masterpiece of both reportage and portraiture, Ali was the first heavyweight champ to avoid the clutches of the Mob, which made it possible for others to follow where he led, so that boxing was pried loose from gangsters’ clutches. That revolution was largely invisible to the general public at the time, but his brashness, his refusal to be a good black man (a.k.a. Floyd Patterson, in Ali’s opinion anyhow), the screaming half-crazy mouth on him, we heard that all right, and it was backed up by the power of his fists. And the Vietnam refusal, the fight he took all the way to the Supreme Court and won, persuading the Supremes to vote in his favour in spite of considerable pressure from the White House do otherwise: that made him a part of the counter-culture, even though he would probably not have approved of most of the things the counter-culture got up to in its spare time. (Remnick is good at showing us Ali’s puritanical streak.)

I remember reading Ali’s autobiography The Greatest: My Own Story when it came out. It’s not a good book, poorly ghost-written, and King of the World, amongst its many virtues, performs the service of telling Ali’s story better and more truthfully than he did.

In The Greatest Ali tells how he was supposedly refused service in a Louisville restaurant when he came home from the Olympics with a gold medal around his neck and how he was so alienated by that act of local racism that he threw his gold medal into the river. Self-mythologizing was a part of Ali’s stock-in-trade, and Remnick makes it clear that the story isn’t true, and that its presence in the book, in spite of the editorial presence at Random House of Toni Morrison, had a lot to do with the desires of Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam that Ali portray himself in that way: as a black refusenik of the white man’s culture.

One of the great strengths of King of the World is its portrayal of Ali’s relationship with the Nation of Islam, that half cockeyed comic, half sinister, proto-Scientological Islam-with-added spaceships cooked up by Elijah Muhammad which seduced Ali by its segregationist clarity (white man bad, black man good), as a result of which Ali kept his distance from the civil rights movement and its leaders, seeing them as people who were playing the white man’s game. He also preached a sexual separatism which, perhaps inevitably, he did not practise.

Remnick is excellent on the engulfing, smothering quality of the Nation people, and Ali’s dependence on them. His break with Malcolm X when Malcolm and Elijah fell out is a key moment in this story. Remnick is clear, too, that Ali’s brand of ‘Islam’ led him to treat the women in his life pretty restrictively, even unkindly.

This is emphatically not a hagiography and we are left in no doubt of Ali’s blemishes; but they humanize him, just as Sonny Liston is humanized by his many, and greater flaws. In these pages, Liston comes to life as a rounded character more fully than in anything I’ve ever read. We remember Liston the terrifying hulk, the killer, the wordless monster of whom the young Clay should have been terrified and mysteriously was not. We remember the sportswriters unanimously worrying that Clay might actually be grievously, perhaps even mortally harmed in the fight. But Liston the human being has been a great dark absence, until now.

In these pages, we see the damaged, inarticulate, ill-educated figure of a man, locked into his brutishness, managed by gangsters, his only language the language of his fists. It is a part of this book’s very considerable achievement that Liston becomes almost as sympathetic a figure as Clay: the tragic silence against Ali’s heroic volubility, his doom and descent towards penury the counterbalance to Clay/Ali’s date with destiny.

In the Cassius Clay we first got to know there seemed to be an edge of madness, something genuinely unbalanced behind all that open-mouthed shrieking, but again David Remnick takes us behind the facade and shows us how Ali used the ranting to psych himself up, to banish fear and the thought of defeat until victory was the only possibility; and also how calculated it was. He knew he was a box-office and his mouth brought in the dollars.

But away from the cameras, he was all professionalism. He worked and worked and worked. This too is an Ali we haven’t quite seen before, the nonstop training, the commitment, the hard graft: the man who reached the top because he knew what it took and put in the hours that were needed to turn talent into glory.

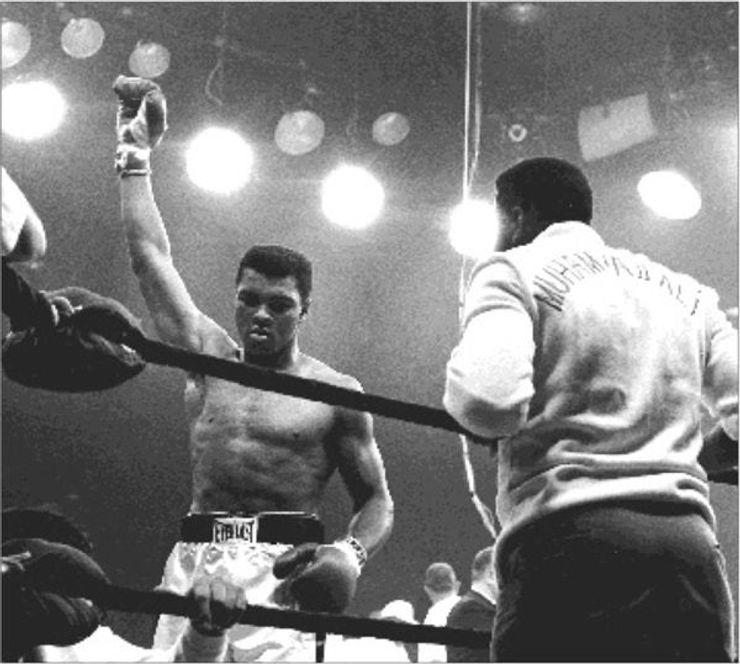

It has been an age of great sportswriters and Remnick mentions several, but with this book he places himself alongside Plimpton, Talese, Mailer and the rest. He takes pleasure in writing about the writing, showing the writers’ part in the creation of the myths of boxing, the heroes and villains, the rises and falls. And in his account of the two Ali–Liston fights his own prose becomes supreme. He takes us into the meat of the contests as if he were right there in the ring, hearing the blows land, being drenched in sweat and blood, bringing it to us from the inside. It’s some of the best writing about combat I’ve ever read, and it makes you feel Ali’s arrival at the pinnacle, moment by moment, the dancing, Liston’s wild lunges swooshing through empty air, Ali’s blows thudding home, the shock of Liston refusing to rise from his stool (first fight) or from the canvas (second fight), the truth about the illegal stuff on Liston’s gloves that got into Ali’s eyes and half-blinded him (first fight) and about the so-called ‘phantom punch’ that ended it once and for all (second fight). And the young champion screaming at the great sportswriters who had written him off. Eat your words!

In short: it’s a knockout. Which is enough preamble. Ladies and gentlemen: the heavyweight championship of the world. Round One.

(Bell.)

King of the World, David Remnick's classic biography of Muhammad Ali, is out now.

King of the World

by David Remnick

When Cassius Clay burst onto the sports scene in the 1950s, he broke the mould. He changed the world of sports and went on to change the world itself. King of the World is the story of an incredible rise to power, a book of battles fought inside the ring and out. King of the World is the story of Muhammad Ali and a classic piece of non-fiction.

Dive into more of the best books about sports for motivational stories that will inspire you.