Ring of Bright Water, Eilean Bàn and Gavin Maxwell

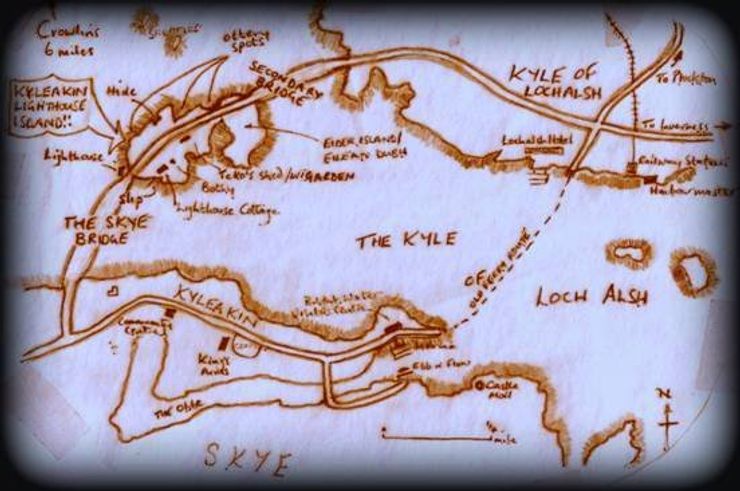

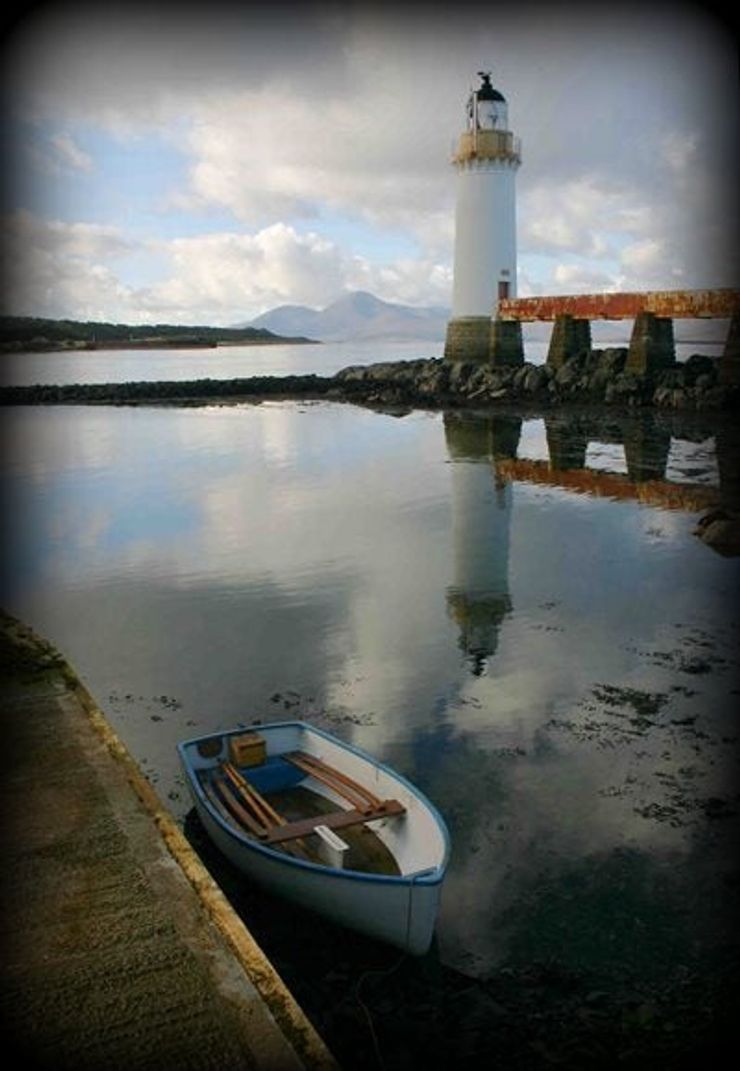

Dan Boothby, author of Island of Dreams, shares memories and photographs from his time living on Eilean Bàn, a tiny island in the Highlands of Scotland and former home to Scottish naturalist and author, Gavin Maxwell.

Dan Boothby had been drifting for more than twenty years, looking for but never finding the perfect place to land.

Finally, unexpectedly, an opportunity presented itself. After a lifelong obsession with Gavin Maxwell's Ring of Bright Water trilogy, Boothby was given the chance to move to Maxwell's former home, a tiny island on the western seaboard of the Highlands of Scotland.

Island of Dreams is a beautifully written account of his time living there and his quest to better understand the mysterious Gavin Maxwell.

We spoke to Dan Boothby about the revival of nature writing, Gavin Maxwell and befriending otters.

Why do you think Ring of Bright Water has had a profound effect on so many people?

Austerity Britain has nothing on the austerity, drabness and general greyness of post-war Britain. We, along with our allies (especially the USA), may have won the war, but it was bad in Britain – always raining in the bombed-out city centres, where drudges dressed in demob suits trudged through puddles to and from their bedbug-infested tenements along broken pavements to work at tedious, meaningless office jobs for 18 hours a day (if we are to believe the social history writers and/or George Orwell).

Ring of Bright Water, written in 1959 and published on 12 September 1960, was about adventure and light and nature, set amidst an impossibly romantic setting. It is a book about a man who has escaped, and who has entered into a (meaningful) relationship with the natural world, and who has befriended an otter, two otters…

How strange, and how delightful!

The dust jacket, too, of the first edition is beautiful, evocative, romantic. How could dreamers trapped in a loveless marriage with post-war Britain not fall in love with the whole package of that book, yearn to escape the dreariness, dream of emulating such a life? And Gavin Maxwell was a master storyteller, a brilliant descriptive writer. He painted with words.

In the foreword to Ring of Bright Water, Maxwell presented his thesis:

'[Camusfeàrna…] these places are symbols. Symbols, for me and for many, of freedom, whether it be from the prison of over-dense communities and the close confines of human relationships, from the less complex incarceration of office walls and hours, or simply freedom from the prison of adult life and an escape into the forgotten world of childhood, of the individual or the race. For I am convinced that man has suffered in his separation from the soil and from the other living creatures of the world; the evolution of his intellect has outrun his needs as an animal, and as yet he must still, for security, look long at some portion of the earth as it was before he tampered with it.'

You've had the opportunity to meet many of Gavin Maxwell's friends and acquaintances; which of them do you feel gave you greatest insight into him?

Can we ever truly know anyone, even oneself? Especially at second hand. I wrote something about this in Island of Dreams,

'If we can pigeonhole someone, put him in a cage and label him, we think we’ve got a handle on him. We know what he is and what it is he deals in. But our moods change continually. We’ve daytime and night-time selves, idle times and feeling-sorry-for-ourselves times, bouts of achievement and bouts of lying on the sofa gazing passively into the goggle-box. We’ve sexually efflorescent times and periods when our romantic life is as barren as a megabarchan sand dune marching across the emptiest quarter of the Empty Quarter. We’ve good days and bad. We are all many selves. If we live long we pass through at least three generations and our morals and casuistries, our consciousness and our interests, our tastes and our motivations will change often during our journeying. How to judge?'

I think Maxwell’s Ghost (Gollancz, 1976, and reprinted by Birlinn, 2011) gives a good insight into Gavin Maxwell’s character. It was written by Richard Frere who, after working for Maxwell as a builder on the lighthouse properties, became Maxwell’s business manager. He cleared up the mess. It is a good book, and as honest as any…

Maxwell's great friend Raef Payne observed that Maxwell would have liked you. What do you think he meant by that?

You tell me. It was ambiguous then, when he said it, and remains so. Raef had offered a woodsmokey hitch-hiking stranger (the 19-year old me) dinner and a bed for the night. After dinner we drank a bottle of wine and talked a lot in his lovely sitting room, a fire roaring in the grate. I had wanted to meet Raef Payne for a long time. He had spent most of his working life as a master at a boarding school. He knew all about the dreaming heads of teenagers. He was kind to me.

Do you think you would have liked Maxwell?

Gavin Maxwell died seven months after I was born. In a parallel universe, I think I would have liked to have sat with a newspaper and a pint at a table in a pub somewhere. Maxwell would be sitting nearby, within earshot, relaxed and happy in the company of some of his less posh friends. I’d be able to listen to what they were gassing on about, and try to get the measure of the man. Then I would step to the bar, buy a whisky (maybe a double) and take it across to Maxwell’s table and place it before him and say, “Thank you, sir. Thank you for writing so well, and for weaving such wonderful stories.” Then I’d nod my head at him and walk out the door into the rain.

Perhaps when I'm dead I can do just that, in the great pub in the sky. (Though on reflection, I’d be inclined to stay to listen to whatever he might have to say by way of a response to my gesture. However, it’ll be eternally sunny up there, so I’ll be lying about catching up on my reading, endlessly, on the rabbit-cropped sward in the beer garden.)

The story of the curse put upon Maxwell by poet – and friend, until a blazing row – Kathleen Raine overshadows Maxwell's final years: the otter Mijbil was killed, a fire destroyed his home and he was taken by cancer. Do you think he believed in the curse?

I think he thought it made great copy. Maxwell was always mining his past for stories. He seemed to rather enjoy writing about the paranormal – the poltergeist activity at Sandaig, the ghosts said to haunt the island. Kathleen Raine’s curse made for a good story. He wraps a whole book (Raven Seek Thy Brother, 1968) around it, and he could cosh Kathleen over the head with it. Poor woman.

Maxwell portrayed himself as recluse, but was, by many accounts, thoroughly garrulous in company. What do you think was the source of his contradictory nature?

An artistic temperament... Douglas Botting, Gavin Maxwell’s biographer, opines that Maxwell was bipolar. But Maxwell also drank a lot – which might explain those expansive evenings. I’m not sure Maxwell was an alcoholic, but drink was in his life (as it was in many more people’s lives in those less puritanical, post-war years). Hangovers make you crotchety, drink makes you contradictory. Also, by the time (and probably before) the house at Sandaig burnt down and he moved to the island, Maxwell was dying. Though he didn’t know it, the cancer that was to kill him was already eating away at him. When you’re facing an early death (Maxwell was only 55 when he went, in September 1969) or you’re in a lot of pain, there’s a lot of anger to deal with. And status and fame put pressures on people, and he was an outsider, in a world that was very tightly-wrapped.

Are you still in touch with the Bright Water Visitor Centre? What do you think Maxwell would have made of its existence?

One of the trustees made contact with me not so long ago to say that they’d been waiting a long time for Island of Dreams to appear, and that it had been worth wait. I hope that means that he approves of my book. I hope that readers can see that it is a kind book. There is no malice meant there. I wrote the book to understand an obsession I had, and to remember a place I was in love with, and people who were kind to me. A community may be interested to see how it is perceived, but no-one likes to be judged – especially not by an outsider. So I worry about how the book, and I, will be received up there.

I don’t know what Maxwell would make of the Trust. Most writers have a striking self-regard (however well they hide it) and so I’d imagine Gavin Maxwell would be pleased to see his name and his work remembered. Perhaps he’d want to be involved in the Trust – to try and bend it to his will…

Nature writing seems to be coming back into vogue with British readers. Are there any particular books or writers you'd like to recommend to those who want to read on after finishing your book?

I think travel writing – as a genre – seems rather poorly, sickly even. Have we become a bit too risk-averse? Rucksack-toting ‘travellers’ gave way to ‘backpackers’ gave way to ‘flashpackers’. Rather than loping on down the road into terra incognita for an indefinite period of time with only the telephone and Poste Restante to keep in touch, Abroad doesn’t feel so abroad anymore. We’re all but a few buttons away from home. And a lot of the world has become off-limits and life-endangering.

Nature writing, the literary equivalent of the ‘staycation’, has taken travel writing’s place. Perhaps the transition was already occurring when William Fiennes’ beautiful The Snow Geese was published back in 2002 (so, soon after 9/11).

I don't read much new nature writing, I liked Badgerlands (Granta, 2013) by Patrick Barkham, and Esther Woolfson’s Corvus (Granta, 2008) – but then I like badgers and the crow family. I like re-reading the old stuff – Konrad Lorenz’s King Solomon’s Ring, Gerald Durrell’s Corfu books, Ian Niall, R.M. Lockley, T.H. White’s The Goshawk. There is a bibliography at the end of Island of Dreams, of books that made me want to travel, walk about, observe, write.

Dan Boothby's Island of Dreams is out now. Read an extract here.

Island of Dreams

by Dan Boothby

Dan Boothby had been drifting for more than twenty years, without the pontoons of family, friends or a steady occupation. He was looking for but never finding the perfect place to land. Finally, unexpectedly, an opportunity presented itself. After a lifelong obsession with Gavin Maxwell's Ring of Bright Water trilogy, Boothby was given the chance to move to Maxwell's former home, a tiny island on the western seaboard of the Highlands of Scotland.

Island of Dreams is about Boothby's time living there, and about the natural and human history that surrounded him; it's about the people he meets and the stories they tell, and about his engagement with this remote landscape, including the otters that inhabit it. Interspersed with Boothby's own story is a quest to better understand the mysterious Gavin Maxwell.

Beautifully written and frequently leavened with a dry wit, Island of Dreams is a charming celebration of the particularities of place.