Renewing the Great American Novel

As acronyms go, it comes with a fair amount of baggage. But, as Hannah Williams explores, the GAN is living the American Dream: it can be whatever you want it to be.

The great American novel is one of those concepts that has been treated with such sincerity, such silver-service reverence, that it has become a parody of itself. Or perhaps, in some way, it was always a parody, just one that can’t help being taken seriously. This tension seems exemplified by Henry James’ (himself a Great American Novelist contender) decision, back in 1880, to christen it the ‘GAN’ – an undignified little acronym for such a seemingly large deal. Our relationship with the GAN is permeated by this uneasiness: why can’t we stop thinking about something that seemed ridiculous even as it was conceived?

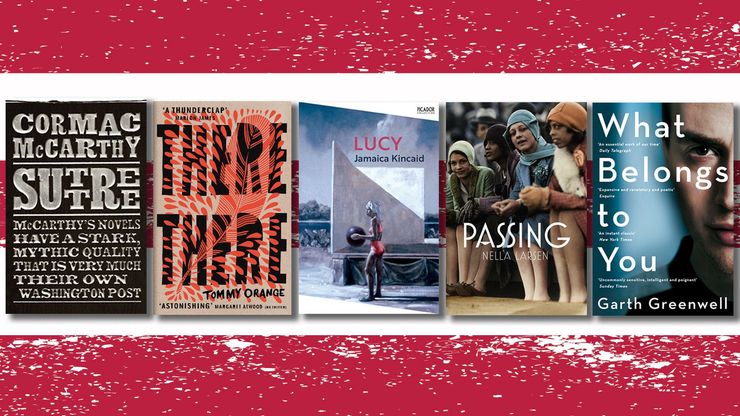

In recent times, the GAN can seem outdated, dominated solely by novels from a certain type of writer: usually white and male. That isn’t to say that these books shouldn’t be considered part of the canon, or that they aren’t worthy contenders for the GAN crown. For instance, it seems ridiculous to claim that the usual novels –Moby Dick or The Scarlet Letter or The Great Gatsby or the U.S.A. trilogy or Infinite Jest – aren’t great American novels. Of course they are; they’re urtexts, masterpieces that have irrevocably moulded the shape of American literature in their own image.

But it feels timely to wonder what an updated canon of GANs could look like. Which authors could be included? Would there be the same emphasis on length, scale and breadth, on settling the frontier-expanse of the blank page? Or would there be something else entirely, a new way of understanding what a Great American Novel can, should and will be?

What Belongs to You

by Garth Greenwell

The story of a university professor’s infatuation with a sex worker, What Belongs to You’s Bulgarian setting may intially seem to exclude it from being the Great American Novel. But what could be more American than running from the puritan repression of the new world to the concrete-pocked freedom of the former Eastern bloc? That’s precisely what What Belongs to You’s unnamed narrator does. It doesn’t work, of course – it never does – but the Americanness lies in the possibility that you could, perhaps, reinvent yourself, that you could leave it all behind, that you could become who you secretly dreamt of being.

Passing

by Nella Larsen

Although never mentioned as a GAN, Passing is already considered a classic, and for good reason: it’s a brilliant meditation on privilege, power and belonging. It follows two light-skinned black women: Irene, a doctor’s wife in Harlem; and Clare, who is living as a white woman, complete with extremely racist husband. The novel is a rumination on the monstrousness of the American obsession with racial identity, and the hallmarks of racist policies and attitudes – anti-miscegenation laws, the one-drop rule, ‘invisible blackness’ – haunt every page.

A Little Life

by Hanya Yanagihara

In terms of scope, A Little Life seems to fit the classic mould of the Great American Novel. It’s weighty, both physically (it stands at 752 pages, only slightly less than Moby Dick), and thematically, dealing with abuse, drug addiction, sexual trauma and queerness. But it’s in its exploration of generational impact that the novel emerges as a contender, as it traces the ways in which we leave a mark on those around us.

Lucy

by Jamaica Kincaid

Is there a Great American Novella? It’s hard to read Lucy and not be convinced that there should be. In Lucy, our narrator leaves the West Indies for North America, searching for something – for anything – else. But despite having travelled thousands of miles, her own struggles are reflected all around her, whether in the family she works for or the people she sees on the frigid, bright streets. Kincaid’s spare, precise prose is the perfect vehicle for our protagonist’s dawning realisation that can never truly escape the influence of her homeland, no matter where she goes.

(Read more in this guide to Jamaica Kinkaid's books.)

Beloved

by Toni Morrison

Threading together folklore, intergenerational trauma and black motherhood, Morrison tells the story Sethe, a former slave, who is being haunted by the ghost of her dead daugher, Beloved. The novel presents the horrors of slavery as a waking nightmare, as a demonic spirit, as the spectre of a past that cannot leave the present alone. It’s the kind of book that won’t let you forget.

Suttree

Cormac McCarthy might seem a strange inclusion for this list. After all, he’s probably one of America’s most acclaimed writers, and Blood Meridian is often spoken of as a canonical Great American Novel. But in comparison Suttree, his fourth book, never seems to get the adulation it deserves. It’s a strange, melancholy book, beautiful and violent in equal measure. But what makes it deserve its GAN status is the way its forefathers – Huck Finn; Absalom, Absalom!; Walden – wind through the novel like the Tennessee River on which our protagonist lives.

(You can find out more in our guide to the work of Cormac McCarthy.)

There, There

by Tommy Orange

In There, There, Tommy Orange offers an unshrinking and resolute examination of what it means to be both American and Native American. A mixture of non-fiction and fiction, vignette and narrative, the novel moves between ever-shifting perspectives, characters and identities. it is unrelentingly ambitious, both in its scope and in its unpicking of the ramifications of centuries of colonial violence.

Play It As It Lays

by Joan Didion

It isn’t any surprise that Play It As It Lays is not touted as a GAN. Most of its 224 pages are only half-used, fragments of text tumbling across the blank surface like ice cubes in a whisky glass. But what marks Play It As It Lays as a Great American Novel is its ability to understand the void that lies at the heart of the American dream, behind the glamour and the parties and lights in the Hollywood hills. “I know what “nothing” means, and keep on playing,” our protagonist tells us in the book’s last line.