Mieko Kawakami's books: a complete guide

Naomi Frisby on literary sensation, Mieko Kawakami.

When Mieko Kawakami appeared on the Japanese literary scene she posed a challenge to its male-dominated status quo. Her novella Breasts and Eggs (Chichi to Ran), published in Japan in 2008, was described as ‘unpleasant and intolerable’ by Tokyo’s then governor, Shintaro Ishihara. The book won the Akutagawa Prize, Japan’s most prestigious literary award, of which Ishihara had previously been a recipient. Breasts and Eggs has now been expanded to novel length, with over 250,000 copies sold across thirty countries and her second novel Heaven followed in its footsteps with fans including Haruki Murakami, Elena Ferrante and Sarah Moss. Kawakami’s literary star is going global.

Here, Naomi Frisby shares all you need to know about this uncontainable talent.

Kawakami was born in Osaka in 1976 to a family who were poor, and her father was largely absent. By fourteen she was working in a factory making heaters and electric fans. A job as a hostess followed, before a singing career which she quit several albums in after becoming frustrated at the lack of autonomy. Her thwarted desire to write her own lyrics led her to poetry and a debut collection which won the prestigious Nakahara Chuya Prize. She also found fame as a popular blogger, writing frank posts in her own dialect about sex, family and life as a woman.

It is these preoccupations that form the basis for Breasts and Eggs, which asks questions about the systemic oppression of women and its impact on individuals. Makiko, a bar hostess, contemplates breast implants in order to maintain a youthful look alongside her younger co-workers, while her sister Natsuko wonders whether or not she wants to become a mother. There are no easy answers for either of the women, their decisions made more complex by having been raised in poverty.

‘I want to write about real people,’ says Kawakami, and it’s clear that this intention has resonated with those who rarely see their lives on the page. Her interest in memory, which she considers ‘as important as life itself’ coincides with her desire to document these stories. ‘There are just as many memories as there are people, so there’s no correct version of one event,’ she says. ‘That’s why we need many different kinds of voices and experiences and by reading those voices we understand and construct a bigger picture of the world’.

The wish for a broader perspective includes the lives of children. In Heaven, Kawakami’s first full-length novel in Japanese which was published in 2009, two teenagers are bullied by their peers. The unnamed male narrator and his female classmate form a secret alliance through which they begin to explore the possible reasons for their fate. Taking inspiration from Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Heaven questions the nature of good and evil and provokes the characters into a search for meaning in violent acts. In her review of the novel, Yumi Toyozaki writes, ‘the conversations between characters and the long monologues summon a deep spirituality that makes the world of fourteen feel enormous.’

Describing herself as ‘quite a philosophical child, asking odd questions and in a hurry to grow up,’ Kawakami chose to explore childhood because, ‘coming to the realisation that you’re alive is such a shock. One day, we’re thrown into life without warning. We often talk about death being absolute, but I can’t help thinking that being born is no less final.’

Life isn’t the only thing that Kawakami experiences with such a surge of energy. She sees a connection with her approach to writing. ‘I tend to write with a structure that has an explosive ending. It’s like something is filled to the brim until it all spills over with great force.’ The process of divining whether a piece is poetry or prose happens before she begins to write. ‘It’s all subconscious. I think it’s already separated from the start.’

Kawakami’s drive to create, her need to write about people not often taken seriously – working-class women and children – and the fearlessness with which she conveys their stories has established her as one of Japan’s best contemporary writers. Heaven was repeatedly hailed as ‘a masterpiece’ by Japanese reviewers and won Kawakami the Ministry of Fine Arts Award for Debut Work as well as the Murasaki Shikibu Prize. Haruki Murakami described her as ‘always ceaselessly growing and evolving.’ That there is more to come from this unique, eminently readable and exciting writer is cause for explosive celebration.

Mieko Kawakami's books in order

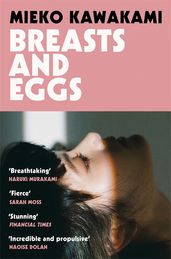

Breasts and Eggs

by Mieko Kawakami

In a Tokyo where lives teeter on the precipice of transformation, Breasts and Eggs offers an intimate, unflinching look at the lives of women caught between cultural expectations and personal yearning. Natsuko – a writer struggling with creative stagnation – is thrown into a spiral of self-examination when her sister, Makiko, arrives, consumed by a desire for breast augmentation, dragging along her teenage daughter, Midoriko, who is mute with angst over her own emerging womanhood. Kawakami’s narrative pulls readers into a visceral exploration of body autonomy, societal pressure, and female identity. Layer by layer, the story peels back the characters' internal conflicts to examine the disquiet that simmers beneath the surface of ordinary lives.

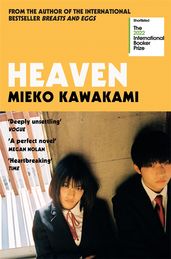

Heaven

by Mieko Kawakami

In Heaven, Mieko Kawakami crafts a haunting portrayal of cruelty and resilience through the eyes of a fourteen-year-old boy relentlessly bullied for his lazy eye. Isolated and resigned, he forms a fragile, clandestine bond with Kojima, a fellow classmate who endures her own torment. Together, they create a private refuge, sharing letters and moments of solace, yet their friendship also raises questions about suffering, dignity, and the choices one makes to survive. Kawakami’s poignant character study reveals the psychological scars of violence and the complexities of empathy, drawing readers into a raw, heartbreaking contemplation of how we understand – and misunderstand – the pain of others.

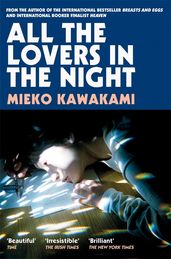

All the Lovers in the Night

by Mieko Kawakami

Fuyuko Irie lives in quiet isolation, drifting through Tokyo as a proofreader who has perfected the art of invisibility. She spends her days steeped in routine, tethered to a life of numbing solitude. But a chance encounter with Mitsutsuka – a man who sees beyond her quiet exterior – stirs something dormant within her, bringing both a flicker of hope and painful memories to the surface. As Fuyuko’s inner world unfolds, Mieko Kawakami tells a story of loneliness, self-discovery, and the risks of reaching beyond one’s comfort zone. The novel speaks to the courage required to confront the chasms within and to seek genuine connection, even when it means unravelling the protective barriers of a carefully constructed life.