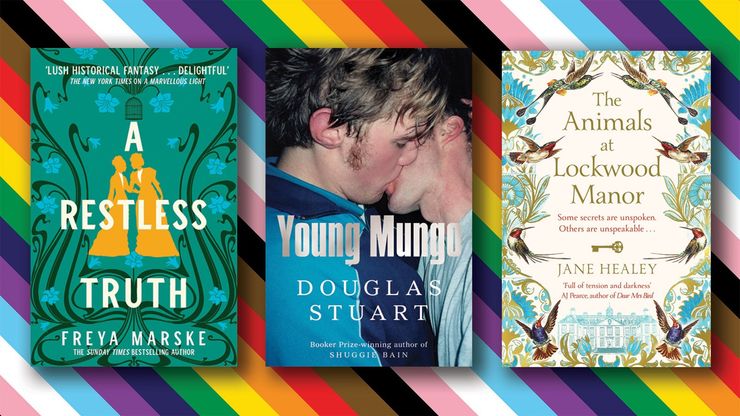

Lucy Scholes on Hanya Yanagihara’s The People in the Trees

The People in the Trees is the stunning debut novel from Hanya Yanagihara, author of A Little Life. Here journalist Lucy Scholes discusses the immersive world Yanagihara creates in the novel and the theme of power that runs throughout the story.

Hanya Yanagihara’s haunting first novel begins with two press reports. The first recounts the news that one Dr. Abraham Norton Perina, the 71-year-old “renowned” immunologist and recipient of the Nobel Prize, is facing charges of sexual assault and the statutory rape of a minor. The second reports his sentencing—twenty-four months in prison for the rape of his adopted son, one of the forty-three children native to the Micronesian country of U’ivu whom Perina adopted in the course of four decades of association with the islands.

Back in 1950, Perina, then a young researcher with a penchant for killing lab mice, joins an anthropological expedition searching for a rumoured lost tribe native to Ivu’ivu, the undeveloped second of the three islands that constitute U’ivu. As well as discovering the tribe they’re looking for, the team also happens across a group of near feral forest dwellers who exhibit varying degrees of senility even though their bodies remain physically youthful. Perina comes to suspect that the source of this corporeal longevity is a rare turtle, considered sacred by the islanders, the meat of which is ceremonially eaten by Ivu’ivuians who reach their sixtieth birthday. Unable to resist the notoriety the discovery of the secret to eternal life will bring him, Perina kills one of the beasts and smuggles its meat back to America. This makes his name but it also seals U’ivu’s fate. Researchers flock to the islands, swiftly followed by big pharmaceutical companies.

It’s a striking tale of Western hubris, steeped in strange totemic, fable-like elements and a host of literary references from The Book of Genesis, through The Tempest (from which the novel’s epigraph is taken), and Frankenstein (Perina names the adopted son who’s the eventual cause of his downfall Victor like Mary Shelley’s protagonist). But it’s also firmly grounded in fact, Yanagihara having explained that she wanted the story to evoke what colonization wrought on Hawaii—her father is Hawaiian, and Yanagihara spent much of her childhood on the island—while Perina is based on the Nobel Prize-winning medical researcher and convicted paedophile, Dr. D. Carleton Gajdusek.

There is much to admire about Yanagihara’s writing; first and foremost, its verisimilitude. She constructs a living, breathing world, from the history and folklore of U’ivu, down to her lush, meticulous portrayal of Ivu’ivu’s flora and fauna, all perfectly described in the vernacular of a man of science caught between objective reportage and an uncanny sense of wonder. “I felt as if the jungle were constantly showing off to itself,” Perina writes—the main body of the text is his Humbert Humbert-style memoirs, written during his incarceration—“every rock, every tree, every surface that would stay still was trimmed, bedecked, baroque with greenery: there were fistulas of bushes wrapped with creeping vines and spotted with moss and lichen and trees draped with great valances of hairy, hanging roots from some other unseen plant that lived, I imagined, high above the canopy. Things flew up from the floor and trickled down from the treetops. It was an exhausting performance that never ended, and for what? To prove the imperturbability of nature, I suppose—its unknowability, its fundamental lack of interest in humanity.” As if this wasn’t enough, footnotes reference a veritable library of attendant fictional journal articles and books. The exhaustiveness of Yanagihara’s vision is awe-inspiring.

To read The People in the Trees is to fall under the spell of the world therein, and to find oneself hanging on Perina’s every word. This is dangerous, of course, but as befits a writer so fully committed to her own creation, Yanagihara fearlessly pushes her readers to their limits, and then beyond. As well as detailing horrific sexual violence, her second novel, the stunning Man Booker-nominated A Little Life courageously replicated the frustrations of an abuse survivor trapped in the never-ending legacy of trauma. Here, by boldly allowing Perina to narrate his own story, we see a similar case of abuse but from the other side. This leaves us wrestling with the unsavoury conundrum of a great scientist who did evil things. Given the myriad recent conversations about what to do with the art of monstrous men, there couldn’t be a better time for this novel to re-enter the world. What’s clear though is that Yanagihara never portrays depravity for gratuitous sensational effect, but rather she’s deeply concerned with the distortions and misuses of power at work between the colonizer and the colonized, the scientists and the U’ivuians, Perina and his children.

The People in the Trees

It is 1950 when Norton Perina, a young doctor, embarks on an expedition to a remote Micronesian island in search of a rumoured lost tribe. There he encounters a strange group of forest dwellers who appear to have attained a form of immortality that preserves the body but not the mind. Perina uncovers their secret and returns with it to America, where he soon finds great success. But his discovery has come at a terrible cost, not only for the islanders, but for Perina himself.