The secret lives of the Hemingway wives

From the beginning of his first marriage, Ernest Hemingway was never without a partner, and Hemingway's wives were four extraordinary women. Naomi Wood, author of Mrs. Hemingway, tells us more.

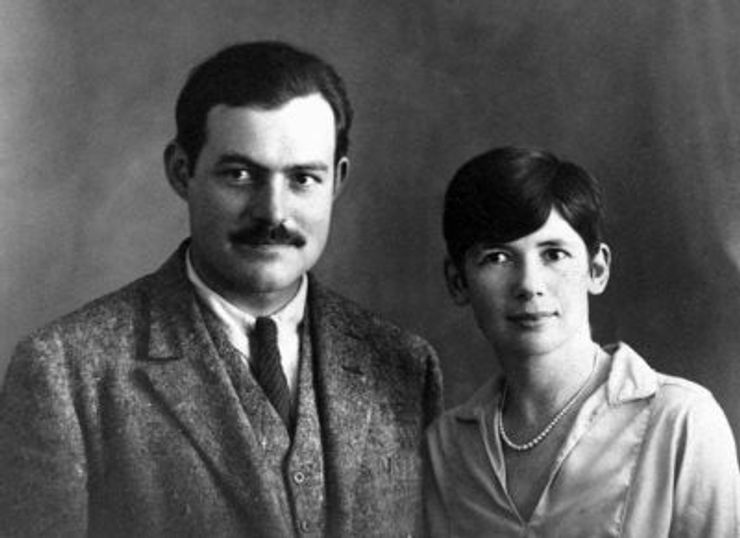

From his first marriage to Hadley Richardson in 1921, to Pauline Pfeiffer, Martha Gellhorn and Mary Welsh, Ernest Hemingway’s wives were four extraordinary women. While his literary career went from strength to strength, his marriages were full of passion and deceit. Here, Naomi Wood, author of Mrs. Hemingway, recalls the moment she realised she had to write a novel about the four Hemingway wives. All photos courtesy of the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.

‘‘It would be a swell joke on tout-le-monde if you & Fife & I spent the summer at Juan-les-Pins…’ ’

— Hadley to Ernest Hemingway, May 1926

I remember the moment I read this line. I remember it because it left me stunned. Hadley effectively writes it would be fine – no, swell! – for Ernest’s mistress Fife to holiday with them that summer.

How could a loving wife knowingly invite her husband’s mistress on their trip? I checked over my notes: Hadley had known about Ernest’s affair with Fife, and still she had invited her. In Antibes, there were always three breakfast trays and three swimsuits drying on the line: ‘There we were à trois,’ Hadley later told her biographer, ‘that summer seemed to last a year.’

From then on I was hooked. I wanted to find out what made the four Mrs. Hemingways – Hadley, Fife, Martha and Mary – attracted to Ernest; so attracted that they often thought a marriage of three was better than a woman alone.

What dazzled me most was how the carousel of wives and mistresses whipped around each decade. Martha Gellhorn, Ernest’s second mistress and third wife, spent weeks sunning herself in Ernest and Fife’s garden in 1937, just as Fife had spent the summer with Mr. and Mrs. Hemingway in 1926. (‘I don’t mind Ernest falling in love,’ Fife wrote, ‘but why does he always have to marry the girl when he does?’)

In another letter, addressing her as ‘Cutie’, Martha thanks Fife for letting her become a fixture in her house – adding, ‘Ernest’s work is pretty hot stuff…’ Two months later, Martha and Ernest were having an affair. Fifteen days after his divorce in 1940, he married Martha, and he sent Fife the kill from the honeymoon hunt. Nice.

Though the wives and mistresses of Ernest Hemingway were often enemies, they were often also friends. In Mary Welsh’s words, they were all graduates of ‘the Hemingway University’. In fact, Fife and Mary spent many a summer together in Cuba in the 1940s. A strange sisterhood indeed.

After Hadley, the woman celebrated in A Moveable Feast, Hemingway went on to share his life with three other spectacular – and patient! – women for three more decades. In writing Mrs. Hemingway I wanted to illuminate the experiences of all four Hemingway wives: some of whom have been celebrated, some of whom have been maligned, some of whom have been forgotten.

But at the end of the day, I wanted to show how it might have felt to be in love with such a talented and difficult man – and what it might have been like to be loved by him. Martha’s phrase was ‘in the beam’. Her words are apt: when you look at photographs of Ernest Hemingway, it’s his eyes that shine out at you, as if a lamp has been turned on in a room. Being in love with him must have been like being in that beam of light. And, when this light was turned off, it must have been a very heavy darkness indeed.

Mrs. Hemingway

Mrs. Hemingway charts the relationship between Hemingway and his first wife Hadley, who are accompanied on their holiday in the South of France in 1926 by his lover Fife.

Hadley is the first Mrs. Hemingway, but neither she nor Fife will be the last. Over the ensuing decades, Ernest’s literary career will blaze a trail, but his marriages will be ignited by passion and deceit. Four extraordinary women will learn what it means to love the most famous writer of his generation, and each will be forced to ask herself how far she will go to remain his wife . . .