Garth Greenwell discusses Cleanness and queer art

Cleanness is the highly anticipated second book from acclaimed author Garth Greenwell. Here, Garth and his editor Kris Doyle discuss this second book of fiction, the ways in which power shapes our relationships and how art can help to dismantle the dichotomy between queer and universal experience.

Garth Greenwell’s debut novel What Belongs to You, the story of an American teacher in Bulgaria involved in an increasingly intense and unsettling relationship with a young street hustler, was hailed as an ‘instant classic’ by The New York Times. Cleanness is his highly anticipated follow-up, a book of fiction which expands the world of the narrator of What Belongs to You. As he prepares to leave the country he has come to call home, the narrator reflects on the intimate relationships that have coloured his past, from a queer student’s heartbreaking confession to sexual encounters both brutal and loving.

In this conversation, Garth speaks to his UK editor Kris Doyle about Cleanness, how power structures shape even our most intimate relationships and the challenge of representing the reality of sex in literature.

KD: Hi Garth

GG: Hi Kris!

KD: So, I’m super sad that you’re not here in London for the launch of the book! I was so looking forward to seeing you again. But it’s really nice to have this opportunity to talk to you about it. Before I ask my first book question, are you OK with all the Covid-19 stuff? Are you writing from home in Iowa?

GG: I’m so sad too, not to be with you in London! It was going to be the highlight of my spring. But we are, so far, having a blessedly lucky isolation. I am in Iowa City, which is weirdly calm, with the university students gone. My partner and I are in our new house, which has created a state of weirdly conflicting emotions: on the one hand, the anxiety and stress and grief of the pandemic; on the other, the pleasures of being together, and of seeing our first spring in our house, all our trees in bloom. But we’re fine, and our loved ones are fine. We are counting our blessings.

KD: Yes, we’re much the same. I’m taking an inordinate amount of pleasure from blossom! And am very grateful our families are well, even amidst the awfulness all over the world. I have been reading more, so I’m going to use that as a segue into book talk. We’re here to talk about Cleanness, which we will publish in the UK in a couple of weeks. My first question, which is always my first question, is how would you describe the book (briefly) to someone who was hearing about it for the first time?

GG: It’s actually a hard question! The book is about an American high school teacher living and working in Sofia, Bulgaria. It covers a period of three or four years in his life. If I had to sum it up in a single word, I think I’d say that it’s about intimacy: the intimacy of love and of sex, which has been the focus of a lot of the discussion about the book here in the US, but also the intimacy of teaching and friendship, and the strange intimacy that is citizenship, that is belonging to a place and the people who live there. It shares a narrator and a setting with my first novel but isn’t a sequel: the books stand alone, and no one needs to read What Belongs To You before reading Cleanness. But they speak to each other and intermingle in ways that I hope will give pleasure to people who are familiar with the first book.

KD: That’s a really good answer and I’d definitely like to talk about some of those subjects here. Amusingly, you’ve pre-empted my second question. I was going to say, would you describe it differently to a reader who was already familiar with What Belongs To You and explain how they relate, but you’ve kind of covered that. The reason I say so was because I think the first book won you a lot of readers (compared to most first novels) and I think many people who come to Cleanness will be familiar with What Belongs To You, but of course not all, so I was curious if your description of the book would change for someone who had read What Belongs To You?

GG: One of the first things I knew about What Belongs To You was that it needed to be a very streamlined container: that the structure of the book needed to be as tight and focused as the obsessive relationship at its heart. I knew that the world the book was coming out of was bigger than that container. So much had to be left out. That was bearable to me because I knew there would be this other container, a book that could be more open and mobile, more interested in the social world, not so tightly focused. Cleanness is a bigger book, I think – not in terms of pages, but in terms of characters, places. And also in terms of affect and mood. I hope that it strikes more notes, that its emotional palette is broader.

KD: It definitely does! The form helps with that, I suppose. But I totally agree with the increased scope in terms of character, place, mood, emotion – everything really. So I think you’ve achieved that ambition! Let me just go back to your original description of the novel as being about intimacy. We will probably talk about sex and the other things that have come up in the USA, but I’m delighted you’ve mentioned teaching above. When I think of the book, I wouldn’t exactly say it’s about power, but power is a word I come back to again and again. It’s part of the relationships in many ways: whether love, or the S/M relationships in the second and penultimate stories, but probably in a less talked about way, it’s crucial to the role of the teacher in the first and final stories of the book. Were you conscious of the teacher-student dynamic as being like that of a romantic relationship?

GG: I do think the book is about power, and about the ways that power structures our sense of intimacy. I don’t think any relationship is free from it, and something that fascinates me is how the balance of power can shift, sometimes in tiny but hugely important ways. I don’t think any relationship between people is free of power dynamics – but I’m also not convinced that intimacy is reducible to power dynamics; I’m also interested in a kind of surplus – of affect, of selflessness, of self-giving – that can’t be understood through any kind of crude accounting of power. Teaching and sex – especially the kind of S/M encounters explored in the second and penultimate chapters of the book – are interesting to me because they make so much of that power relationship visible; they acknowledge it and script it – and since it’s visible, it can more easily be thought about, interrogated, turned into a source, sometimes, of play and pleasure.

I was a high school teacher for seven years, three of them in the States and four in Sofia. I remember the real shock, my first year, at how intense my feelings were for my students, and at how intense my relationships with them were – how eager they were to talk about their lives, how hungry they were for a certain kind of attention. I’ve never wanted to be a parent, and I discovered working with young people a kind of love I didn’t know I was capable of, a kind of disinterested love, a love that I imagine to be parental. I wanted to take that love seriously, and explore the kinds of intimacies it encourages.

The teacher-student relationship is a powerful and formative one; one thing that took me aback when I started teaching was just how powerful it could be. It’s full of potential to be positive, but it’s also fraught with risk. I was so conscious, as a teacher – especially as a gay teacher, and a young teacher, only a few years older than my 12th-grade students – about establishing firm boundaries. I was so conscious of what kinds of touch were acceptable and what kinds were not, and of how difficult it sometimes was to tell. In the first story, the narrator feels like he fails his student by a kind of inhibition, that his sense of propriety keeps him from offering a kind of solace the student needs. In the last, he feels like he crosses a line in a way that may be unpardonable. I wanted to capture something about the joy I felt in teaching but also the weight of the responsibility it imposes.

KD: Yes, I think it’s about parallels and the way so much of the book is so tightly woven with echoes. So as the narrator listens to his student in the first chapter, he listens to R’s confession a few chapters later in ‘Cleanness’. Or I was thinking of how the role of being a teacher demands a propriety from the narrator towards his student in the last story which sort of mirrors the way a society’s codes of normality dictate what is proper when it comes to relationships between individuals. At that moment a man can’t act romantically toward another because the ethics of teaching say he shouldn’t; at other moments in the book, a man shouldn’t act romantically towards another for other reasons beyond his own control. Does that make sense? I hope so! And if so, can you also talk about the way the book is full of this kind of patterning, echo, symbolism; I found so many pleasurable moments as I was reading it because of that – an obvious example being the way the second and second last stories are sort of opposites.

GG: I think that’s right. Power relationships are never just about individuals – there’s also the larger structures of power – of what is permitted and not permitted – that determine, or nearly determine, how individuals can interact, what kinds of intimacies are allowed. That’s been a focus of both of my books, I think: what it means to be someone formed by those structures, whether the narrator, raised in homophobic Kentucky, or his high school students, coming of age in a Bulgaria that is quickly changing but still a very difficult place to be queer

I’m still not sure I’ve discovered the right way to talk about the structure of Cleanness. It has been interesting to see how the book has been discussed in the US, and how some critics have felt strongly that it is a novel, and others have felt strongly that it is a book of stories. I’m happy for readers to talk about it however feels helpful to them, but neither label feels really right to me, and I’m grateful that Picador is letting me publish it as ‘a book of fiction.’ The chapters stand alone, and they don’t have the usual novelistic stitching. The middle section tells a continuous story of a romantic relationship, but the chapters in the first and last sections aren’t arranged chronologically. My first education was in music, and my first experience of how artistic wholes can be made of parts was singing song cycles. That was really my model for putting together Cleanness: something like Schubert’s Winterreise. I think of each story or chapter as a node of intensity, and of the book as placing them in a kind of constellation. They’re intensely connected and interrelated, but not by the usual logic of chronology or the cause and consequence of plot. Instead, the relationships between them are determined by things that feel musical to me, like key or texture. And yes, motifs: I hope there are images, concerns, gestures that resonate throughout the book, and that deepen each time they appear. And the chapters in the first and third sections are meant to be mirrors of each other, in a way: I wanted to create paired scenes that could get at the complexity of the questions I was trying to pursue, none of which, to me, feel amenable to singular answers.

KD: That’s such a perfect answer. I think the book reads like that, or I read it like that. I also hope the space allows the reader to participate in the book more than a more singular/linear book might; I felt that was where a lot of the pleasure in it was. I think you’re always alert to the complexity of an experience, the need to allow for multiple emotions, for instance, to co-exist. There are lots of examples and I wonder how you take up the challenge of writing about that kind of inexpressible feeling and emotion. For instance, the narrator longs for a loving relationship with R and yet says he was hungry in some other part of himself for the kind of sexual (and to my mind very different) encounter he has in the second chapter ‘Gospodar’. People want contradictory things. But as a writer, you have to put that on the page. How do you go about that?

GG: That’s really a key insight. That state of wanting contradictory things seems central to me – it seems like almost the primary fact about human life. This is a question of sensibility, not argument, but when I think about human life I see a series of double binds. The title of the book comes in here: it seems to me just a truth of human life that there is something in us that wants desperately to be clean, and there is something in us that wants to bathe in filth. That might mean different things to different people – cleanness and filth might manifest in different ways – but for my narrator, one of the most powerful ways they manifest is in sex. The centre of the book, the middle section, is titled ‘Loving R.’, and it recounts a relationship between the narrator and another foreigner, a Portuguese university student, that introduces the narrator to a kind of love he had never imagined for himself, and that much of his experience has suggested is not possible for him. It’s a conventional relationship in many ways: monogamous, domestic. It’s a kind of revolution for him to discover it, to give and receive this kind of love, and one thing I wanted to do in the book – one task I gave myself – was to try to write happiness, to give these characters at least a moment in which, for all the ways the relationship is difficult and fraught, they have an experience of common, profound happiness.

The only appearance of the word ‘cleanness’ in the book occurs in that central section, and there’s a conventional kind of thinking that would associate cleanness and purity with that kind of relationship, and filth with other kinds of relationships the book explores: cruising, say, or S/M encounters. I hope the book finally breaks down those dichotomies – I want it to question and problematize the way we use ideas of cleanness and filth. But more profoundly I hope it suggests that a fundamental idea that much of our idea of morality is predicated on – that the answer to the double bind is to brutally repress one part of what we desire – is false. Our desire for cleanness, for purity, can spur us to acts of great beauty, to a beneficial kind of moral striving; but also I think the desire to be clean is the most dangerous desire in the world, and that if we become overly attached to it we will make ourselves into engines of destruction. One of the questions in the book is whether there is a way to break down the dichotomy of cleanness and filth, to trouble the easy ways we think of those terms, and to imagine a life that can accommodate both desires.

KD: Do you think it’s just our desire for cleanness that’s dangerous? I think we often avoid desires for many things in order to satisfy other people, often romantic partners, but also ourselves. There’s a line in the book where you talk about one of the characters wearing themself down to a bearable size: ‘How much smaller I have become, I said to myself, through an erosion necessary to survival perhaps and perhaps still to be regretted, I’ve worn myself down to a bearable size.’ Often our desires lead us to places that make us uncomfortable with who we are, then we set about repressing them – and that has dangers too! It’s not just a desire for cleanness.

GG: I mean, one of the central beliefs of my life is that nothing good comes from repression – that anything we try to repress will burst out in ways that have the potential to be devastating. The desire expressed in the S/M encounters is also a dangerous one. Something various characters express in the book is a desire to be nothing, a desire to experience a kind of intensity that threatens extinction. That also seems part of the human condition, to me – that there is something in us that desires not to be. The question isn’t how do we repress that desire, or how to scrub ourselves clean of it; it’s instead: what can we do with it? How can we take our desire for negation and make it something that can be productive – productive of pleasure, say, or of sociality, or of meaning, beauty, etc. This is something I wanted to get at in my favourite chapter of the book, ‘The Little Saint’, in which a man’s willingness to engage with his desire to be negated, his desire to be made nothing – when explored within the aesthetic frame that an S/M encounter can be – can turn into something radically positive, can actually be affirming of tenderness, of human connection, of life. Similarly, the narrator is only able to arrive at the acknowledgement of his love for R. – the last line of the chapter ‘Cleanness’, “anything I am you have use for is yours,” is for me the most important declaration in the book – after he can acknowledge that in addition to tenderness and love there is a kind of cruelty in his feelings for R. So it seems to me that the answer is never to repress, but instead to try to find structures that can accommodate and incorporate as many of our contradictions as possible.

KD: Right! I think it’s very hopeful and pretty radical what you’re saying here. I think it will surprise a lot of readers and I think it will certainly challenge many presuppositions, prejudices, the dichotomies you talked about earlier – and more. One other thing that a reader, even a reader of What Belongs To You, might be surprised by in ‘The Little Saint’, which I think is also my favourite section of the book, is the explicit description of the S/M encounter you’re talking about. I don’t want to make you repeat what you’ve said in lots of other interviews, where you’ve stated clearly your intentions about making art from pornographic language, but I’m interested to know if that was a challenge you set yourself or if it came organically from writing that story/encounter between those two people, and if in the editing process you thought you should make it more or less explicit, once you’d had the chance to reflect on how a reader might feel. I mean, I imagine this could well be the most explicit sexual encounter many readers will have come across in a work of ‘literary fiction’.

GG: I did set myself the task, when I was writing ‘Gospodar’, of writing something that was 100% pornographic and 100% high art. What I meant by that was writing the sexual body as explicitly as I could, but doing so while also engaging in the kind of representation of consciousness, of thinking, that I consider my primary goal as a writer. That was what seemed interesting to me – not explicitness in and of itself – but joining that explicitness with a deep inhabitation of interiority. That makes possible a representation of sex that gets at the reality of sex, for me, which is that it is among our most densely packed, richest forms of communication, of being with one another. I wanted to take sex seriously as a form of moral relation – including kinds of sex, like S/M or gay male promiscuity, that are usually treated dismissively. My commitment to writing the sexual body, and especially the queer sexual body, comes organically from that interest, and from a sense that sex is seldom treated in art with the seriousness it merits.

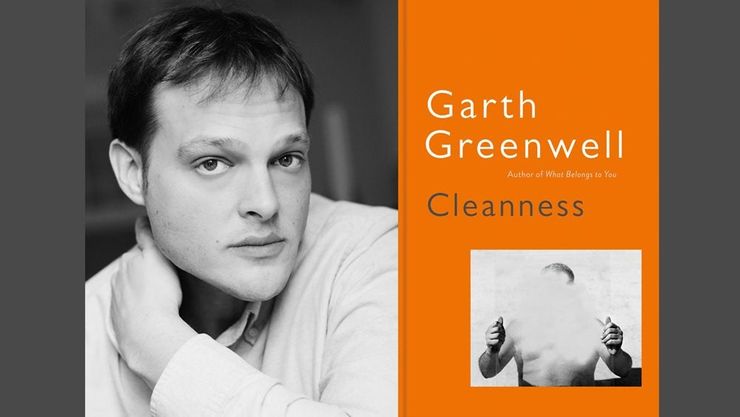

KD: On that point, the UK hardcover has an image of a male body on it; can you just say something about the specifics of the queer bodies in this book? They’re not bodies that would seem from the descriptions as I remember them to conform to the normal beauty standards in the West.

GG: I love the cover for the UK edition more than I can say. It features a photograph by a young, very brilliant artist, Mark McKnight, whose work I was introduced to about a year ago, and when I first saw his photographs I felt an incredible sense of kinship and recognition. It’s true that publishers love to put images of male bodies on my books, especially of a certain kind of young, lithe, androgynous male body. I’ve rejected many first drafts of covers because I think they are expressing an idea of queer art as idealizing a kind of body that actually is not the kind of body I write. Mark photographs male bodies that are decidedly outside the usual canons of beauty – hairy bodies, older bodies, thicker bodies – and he does so in a way that emphasizes beauty. Difficult beauty, troubled beauty, but beauty. That’s what I hope Cleanness does as well. I cannot say what a relief it is to have an image of a body on my book that feels true to the kinds of bodies I write.

KD: I’m very glad you like the final jacket. I think it’s a beautiful book to read and I was keen that in packaging the content, the aesthetic of the book suggested as much to a casual browser in a bookstore.

On your point about queer art. Do you think of yourself as a queer writer? I have slight trouble with this as a publisher in the sense that I am extremely proud of your writing as queer art and I would want the book to be found in queer sections, sold in queer stores, read by queer readers, and I believe it can go out into the world opening queer spaces for readers and doing an immense amount of good. However, it’s also about experiences shared by all humans. I think of you as a truly universal writer. I want to recommend Cleanness to readers everywhere because you’re a queer artist and also not only to recommend your work to them because you’re a queer artist. Maybe it’s about multiplicity again, as we discussed before, and you are and can be all of these things at the same time, but do you feel those labels apply?

GG: The main impetus of everything I do as an artist and educator and critic is the desire to dismantle the dichotomy queer/universal. I am a queer artist, absolutely: I write books centred on queer lives, and one of the traditions I work in is the extraordinary, brilliant, inspiring, vibrant tradition of queer writing. Of course, that’s not the only tradition my work is in conversation with – and all a tradition is is a conversation between artists across time. I also want to be part of the conversation of writers invested in modernist aesthetics, or writers interested in sex, or writers interested in foreignness. Conversations that include Philip Roth and Eimear McBride, not just Alan Hollinghurst and James Baldwin. But I would never want to downplay the centrality of queer experience and queer aesthetics to what I want to do as a writer.

This is the important thing: The whole miraculous purpose of art is to root into the particular textures of individual experience and find in it universal meaning. This is just my core, human faith: that any human experience, put under the weird pressure of art, offers revelations applicable to all human experience. I want to be a queer writer: I want to write from and to queer communities. It’s because of that, not despite it, that my work has whatever universal resonance it might have.

In this video Garth shares just a few of the books that have inspired him:

Cleanness

by Garth Greenwell

In Sofia, Bulgaria, an American teacher grapples with the intimate encounters that have marked his years abroad as he prepares to leave the country he has come to call home. A queer student’s confession recalls his own first love, a stranger’s seduction devolves into paternal sadism, and a romance with a younger man opens, and heals, old wounds. Each echo reveals startling insights about what it means to seek connection. Around him, Sofia stirs with hope and impending upheaval. Expanding the world of Garth Greenwell’s debut novel, What Belongs to You, this is the story of a life transformed by the discovery and loss of love.

Discover the best queer YA books that celebrate diversity.