The Flannan Isles Vanishing: the story behind The Lamplighters

Emma Stonex, author of The Lamplighters, on the real-life mystery that inspired her unforgettable debut novel.

In 1900, three lighthouse keepers vanished from an island in the Outer Hebrides and were never heard from again. Author Emma Stonex was instantly intrigued by the mystery, and as she read more about the vanishing she was inspired to write her debut novel The Lamplighters, a reimagining of the events set in 1970s Cornwall. Here she tells us more about the Flannan Isles Vanishing and the research into the little-known world of lighthouse keepers.

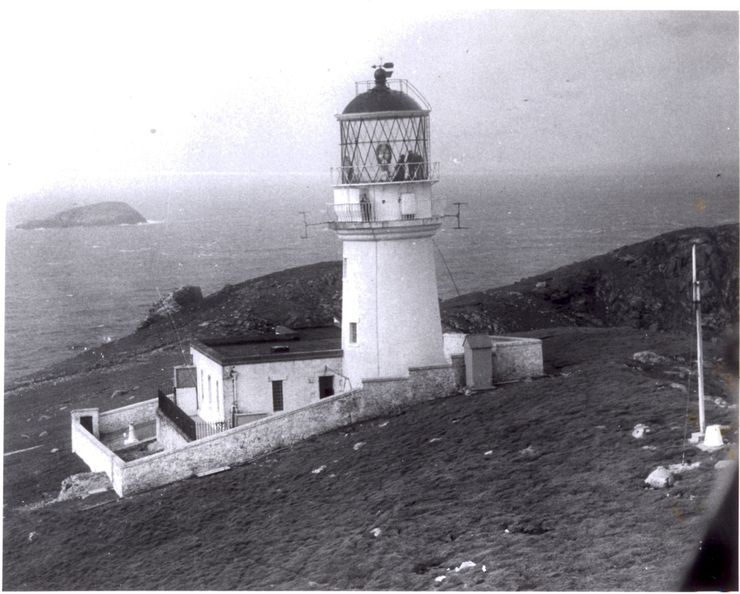

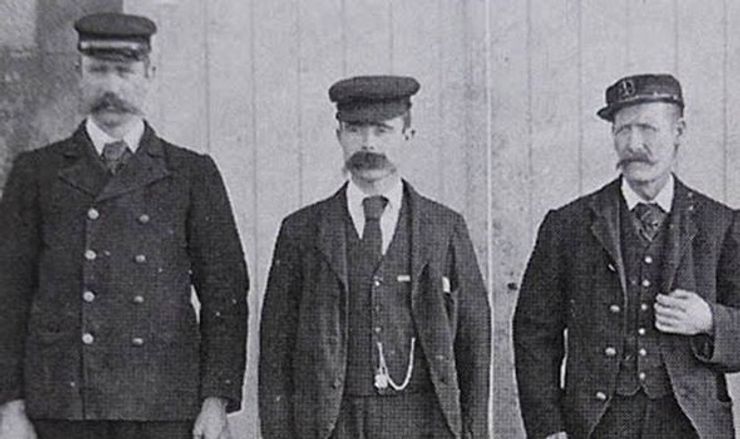

Human beings are drawn to mysteries. Something in us leans towards the unknown, half afraid, half enthralled, always desperate to discover. Throughout history, people have sought other people’s stories – it’s what makes us social creatures, wanting to understand what happens to our fellow species and why. In the case of three lighthouse keepers stationed on Eilean Mòr, a remote island in the Outer Hebrides, who disappeared from their post without trace in December 1900, such answers have never surfaced. A hundred and twenty years later, what happened to them remains an enigma. Did these men drown in a heavy sea? Were they seized by forces earthly or otherwise? What impact did extreme isolation have on their states of mind?

I first encountered the real-life vanishing eight years ago, in a magazine called the Fortean Times. A boat arriving from America noticed, on passing the island, that the lighthouse lantern was not lit. When a relief crew docked, no one came to greet them. The gates and doors were closed, and the beds unmade (a red flag for anyone connected with the service: keepers were meticulous in domestic matters). There was storm damage on the landing stage, and the Principal Keeper’s weather log described tumultuous conditions at a time when records showed no such thing.

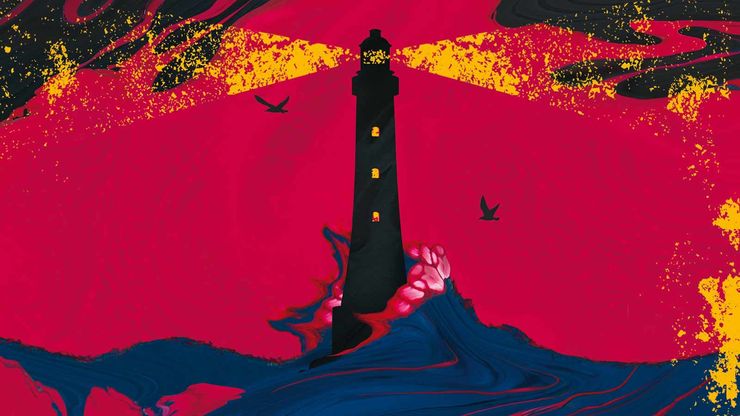

Straight away, I was hooked – not only by the core mystery, the seeming impossibility of three people disappearing into thin air, but the many weird details that accompanied it. The clocks in the lighthouse had stopped. Investigators uncovered a single set of oilskins, suggesting one keeper had been separated from his mates. Wilfrid Gibson’s famous, haunting poem ‘Flannan Isle’ introduced the notion of a table laid for a meal not eaten. Visitors to the island claim to have seen three black birds circling the top of the tower, and strange lights appearing in the sky at night. There lingered a deeply creepy, almost mythical feel to the event, partly a product of that reclusive occupation and partly belonging more generally to the bewitching lore of lighthouses, ingrained in us, calling to us across wild waters, promising a beacon of hope.

The keepers’ names were James Ducat, Thomas Marshall and Donald MacArthur. Ducat and MacArthur had wives and children. Out of respect to those men and their families, I didn’t wish to muddy the waters between fact and fiction. I preferred to imagine their predicament – how it was to be stationed in lonely quarantine for weeks at a time – but not to attempt to speak for people I had never met, and those for whom uncertainty and heartache is still, I’m sure, a reality. I decided to move the incident from a rock (or island) light to a sea tower, the ones that stick up straight out of the ocean, because if that isn’t a setting for a locked-room mystery then I don’t know what is. I transposed the action down to Cornwall, home to the grandest sea stations – the Longships, the Wolf Rock and the Bishop Rock – and to the 1970s, a compelling decade in light-keeping, first for being on the eve of automation and second as a period of increased social mobility, meaning the job was attracting a broader variety of characters and backgrounds.

It was these characters I was fascinated by. The more I examined the original story, the more brightly shone its most captivating feature: the psychology of the people involved. What did it take in a man to work on a lighthouse, trapped in the sea with no one around for miles except the two he was with? How did these absences impact on a marriage? For women in the 1970s, being a lighthouse keeper’s wife could be either oppressive or liberating, depending on which way she looked at it. Some pined for their husbands and hated the sea for carrying him away: their lives couldn’t resume until he returned home. Others embraced a chance at a different way of life, to be head of the household at a time when this position was largely retained by men. Helen in The Lamplighters admits to being content on her own: ‘You’ve had things your way for eight weeks,’ she explains, ‘and suddenly he’s the master of the house and you have to play second fiddle. It could be very unsettling. It’s not a conventional marriage. Ours certainly wasn’t.’

To tell the story with any degree of authenticity – and I wanted very much to present as ‘real’ a view of lighthouse-keeping as I could, as opposed to the romanticised idea prevalent in popular culture – I had to find a way into this notoriously closed community. Over the course of several years, I read as many keepers’ memoirs as I could, noting their similarities (the work routine was amazingly uniform across pretty much every station) and differences – the most significant of which was the attitude: these men loved or loathed the life, and there often wasn’t a grey area in between. Lighthouse by Tony Parker, a very special book I would urge anyone to read, not just those interested in lighthouses but in human nature full stop, informed me deeply. It convinced me that the way to relate this mystery was in the first person, from shifting perspectives. In this way, my characters became like tower lighthouses themselves, disconnected by mutual misunderstandings and yet still reaching for that flare of hope and reconciliation.

While writing, I travelled down to Devon to stay in converted keepers’ cottages. This gave me an insight into what life was like for the families left ashore, living in purpose-built communes that, subject to personal preference, signalled life security or life imprisonment. I have never felt so detached from the world as I did during that stay. My cottage was down a winding, narrow track, miles from the nearest village and as close to the sea as it was possible to be. All I could see was the wide water, vast and indifferent, burning orange at sunrise and dusky pink at sundown, and as I lay in bed listening to the foam on the rocks, the lighthouse beam swept across my sheets and glimmered on the edges of my dreams. Many times, I have revisited that site in my mind. It gave me a sense of the extreme solitude and silence many women experienced as part of the service; of the anthropomorphic qualities the sea adopts when it is all you are seeing every day. We think of the men who kept lighthouses as being the lonely ones, but as is so often the case in history, the women’s experience, equally secluded and equally valuable, is lost beneath the waves.

A mystery is only a mystery for as long as it remains unsolved. The set-up can carry as many intriguing details as you like, but at the whiff of an answer, it loses its power. My challenge with The Lamplighters was to tread the fine line between committing to what I think happened to the keepers, and leaving enough avenues open for readers to decide on their version of events. While The Lamplighters is in many ways a book about the endurance of the human spirit, it is also about this need in us to find resolution, to reach the truth, and ultimately to throw light on dark places.

The Lamplighters

by Emma Stonex

Inspired by true events, Emma Stonex’s debut novel is a riveting mystery which will grip the reader, and a beautifully written exploration of love and grief. In Cornwall in 1972, three keepers vanish from a remote lighthouse, miles from shore. The door is locked from the inside, and the clocks have stopped. What happened to those men, and to the women they left behind?