Edward Carey on how he wrote his novel Observatory Mansions

On the twentieth anniversary of its publication, Edward Carey tells us how a character conjured up from his subconscious with a pencil and paper inspired his debut novel Observatory Mansions.

Edward Carey’s stunningly original modern gothic novel Observatory Mansions celebrates its twentieth anniversary in 2020. Here, Edward Carey tells us how the novel that Jeff Vandermer called ‘the best fiction yet published in the 21st century’ sprang from a character doodle and the enigmatic first sentence ‘I wore white gloves.’

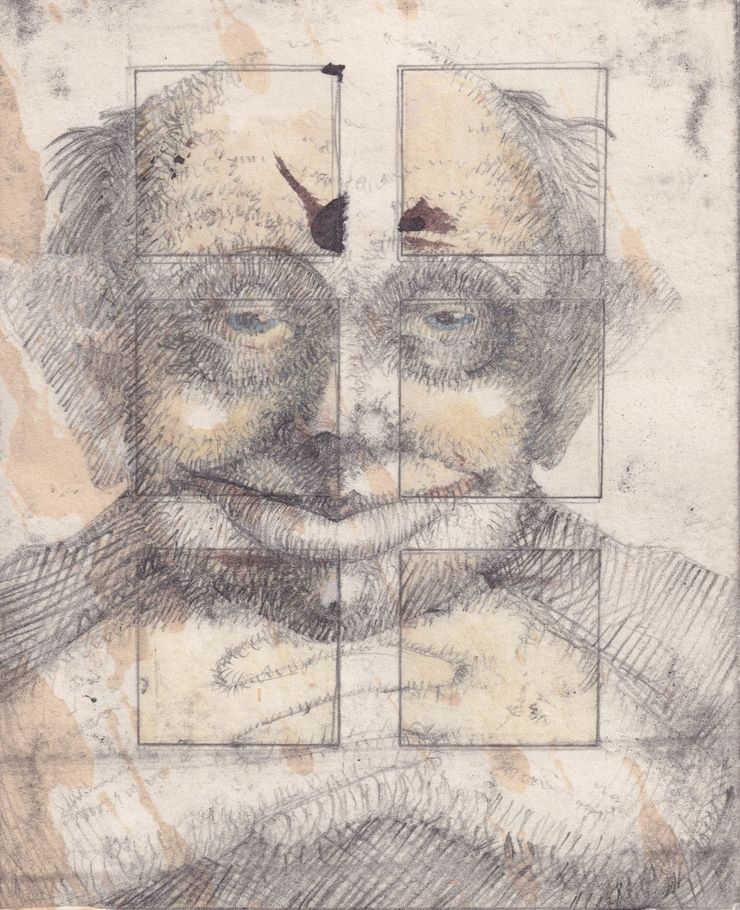

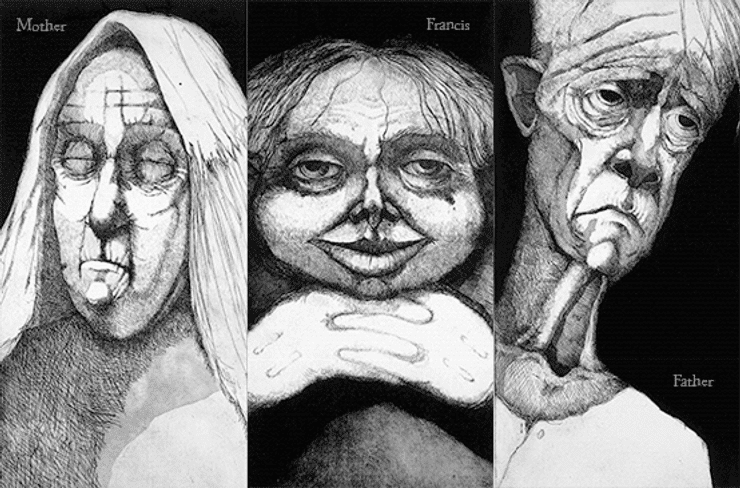

I had been drawing him for a long time. A rather unfortunate looking man wearing white gloves. I didn’t know who he was, I didn’t know what he wanted, but for some reason, often, when I relaxed by drawing, and I often did, doodling without any particular intent, I’d find I’d drawn him again. A gloomy, grinning figure wearing white gloves.

This was twenty years and a bit more ago. I’d been working in the theatre, I was lucky enough to have had a commission in Romania and a show at the Young Vic Studio but now the work had dried up. A friend of mine who was training to be a chef in the Dordogne wrote to me to say that he’d be in Paris for the next few months working, would I like his flat in the countryside? I immediately said yes, probably before he’d quite finished asking the question. And off I went. Theatre was complicated, putting on plays involved lots of people and costumes and sets . . . it was also so expensive. And the plays I wanted to write had lots of characters in them and big operatic settings and it was hard for me to get them produced. But in a novel you can have as many characters and as many sets and as many special effects, you can have strange beasts and planets and whatever you want and it doesn’t cost anything. It’s just a person and a page and on that page: anything, anything at all . . . whatever you like, you can go anywhere. That was magic, surely. I couldn’t quite believe it. Just yourself and anything you summon onto the page. No limits, the only limit was yourself and you could challenge yourself to be braver and braver and let anything in. I was going to write a novel, I decided, a novel about a man in white gloves. That was pretty much all I knew as I arrived in the French countryside. I had three months. I’d better get started. There was no one to talk to, there was just me and my computer and my pencils and pads and cigarettes, I smoked a lot back then. I’d better get started.

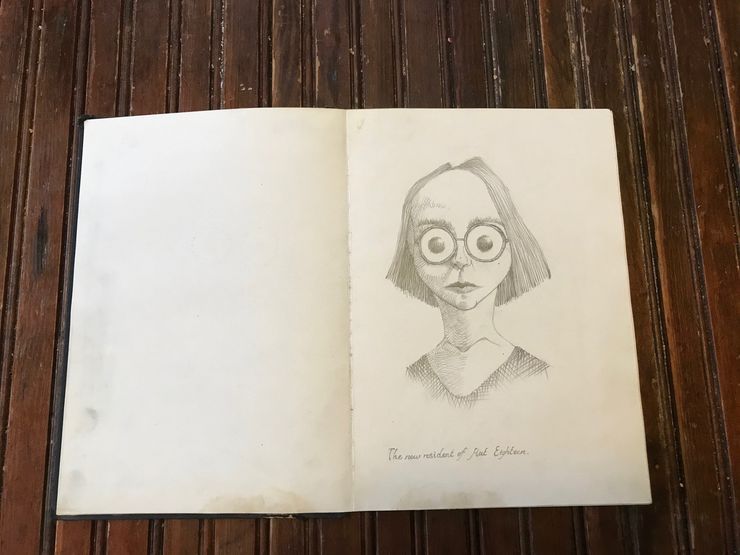

I wore white gloves. That was the start of it, I always knew that was the first sentence. I decided to call this gloved fellow Francis Orme, that sounded right. But where was the story, I wondered? You can’t just have a man in white gloves, what else was there to it . . . I made some notes . . . I didn’t want to write a realistic novel, couldn’t if I’d tried. I decided Francis would live in a big dilapidated building, with lots of other lost people. I decided, very quickly, the house would be his childhood home, an ancient ancestral dwelling, but that his aristocratic family had been running out of money, and land too, they kept selling bits off and the nearby city kept getting closer and closer to the great mansion until it surrounded it and the house ended up stranded in the middle of a traffic island. Yes, that was it and off I went. Builders had turned the mansion into a block of flats . . . yes, on you go . . . and at the time of the beginning of the novel it would be falling apart . . . there was a very real danger that it would collapse. The people remaining in it would be shy and awkward and terrified and odd. And unto these people there’d be a new resident, a young woman who was going blind. Well, that was surely enough to get started with.

But how do you write a novel, I wondered? Well, I suppose, you must write one word after the next, one sentence after the other, one page and then another. And eventually, perhaps, you have a novel. I wasn’t sure but I supposed that was right.

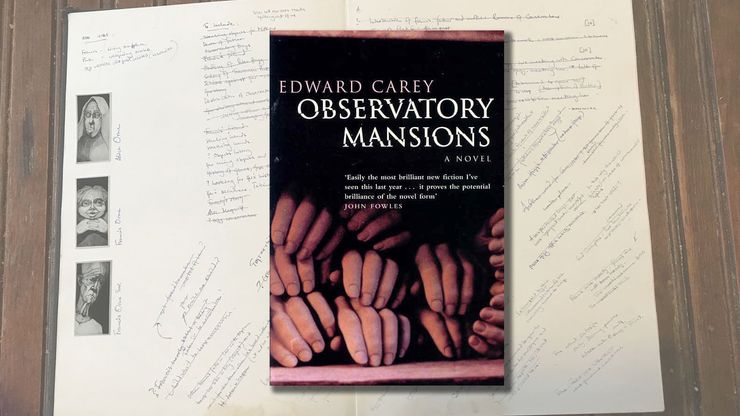

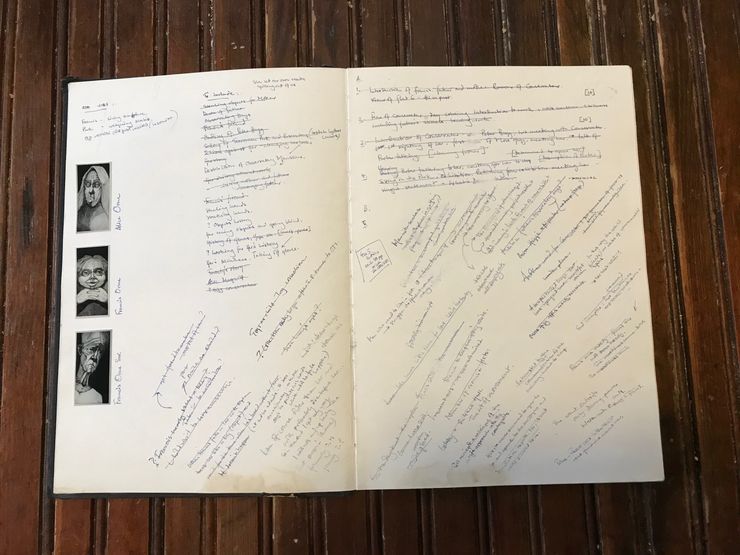

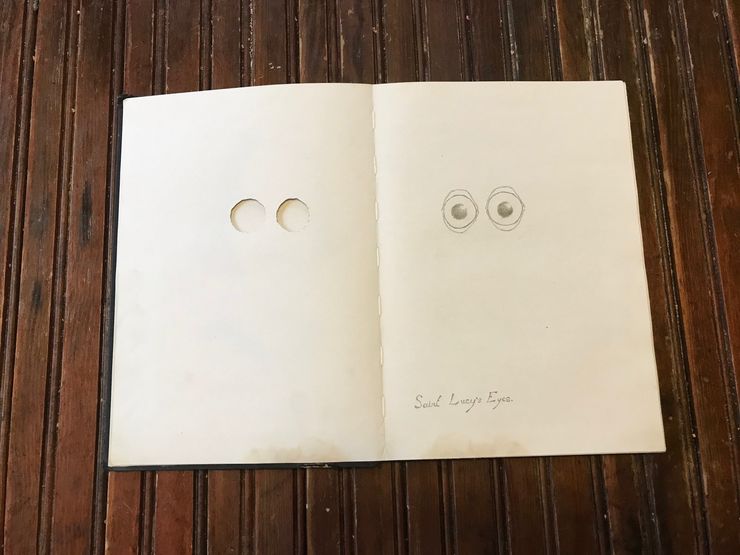

So I sat and wrote and smoked, and words, sentences, pages came falling out. I was in a state of grace that I think that first novelists are often in: it doesn’t really matter if it fails or not. I was doing it out of a sort of joy. I had some time and I was filling it with words. I’d have a go, why not, if it didn’t work, well then I’d know, wouldn’t I – not a novelist, at least not a novelist at this time. Very soon I was lost in it, the words and the drawing, and the smoking, I felt as if I punctuated every sentence by stubbing out a cigarette. Amongst the smoke and the pencils, a draft began to appear. I used bits of my life like many people do. After leaving university I worked in several rather undistinguished jobs around London, one was as a steward at Madame Tussaud’s wax museum – what days those were, days and days of dolls. I’d give my main character a job like that. I’d just come back from Romania, the city I was thinking of in my novel was based on the city of Craiova (cry over) and there were wild dogs all over it and so I had a woman who lived with the wild dogs and thought she was a dog. Also, I’d been reading From the Beast to the Blonde by Marina Warner and this wonderful work on fairy tales had made me rethink my way of approaching storytelling. The novel, I thought, was about memory and love and Francis in his white gloves would steal objects that people loved and store them beneath his home in a tunnel there – there’d be a tunnel connecting the old house to the nearby church made long ago, in case an ancient aristocrat needed to escape to sanctuary. And in that local church would be wooden sculptures of saints and among them would be Saint Lucy who holds in a plate a pair of eyes – she was blinded by her persecutors. My heroine, going blind, had come to the traffic island address because it was close to the church with Saint Lucy in it, so she could pray there for her sight. So it went on and I was lost and there was only the book for me then, three months and a book falling out. And after three months I had a draft, or nearly, and a deficit and a need for a job.

I took the manuscript back home with me to England. I got a job at Foyles – back then Foyles was a very strange place, not the ordered beautiful bookshop it is now. Back then it was an extraordinary chaos and it was much easier to steal a book than buy one. I was with books every day and I read and read. I’d felt brave back in the French countryside where there’d only been me and my book, now I wasn’t so sure. What on earth was I thinking about? I tinkered around with it some more and then, well, I thought, maybe? I sent it out to agents. And the postman brought me all the rejections. None bit, not at first. Then one said, having summoned me in for a coffee in his grand digs, let’s see your next book. I thought, well that’s that then. At last, when I’d pretty much given up, one agent, Isobel Dixon, said yes, and so I told the other agent and he said oh we’ll take you on then and I said no, I’ll go with the one that wanted me straight away. And I did and am still with her now. We worked on it a bit more and sent it out and at last Richard Milner at Picador wanted to meet with us and he said yes, all right then, we’ll take it. A book.

And so here he is. Francis Orme and his white gloves and his crumbling mansions and my first book and twenty years have passed. Two months ago, I recorded it for W. F. Howes audiobooks in a studio in Austin, Texas in the middle of a pandemic. I hadn’t read the thing since I’d gone through my last edits with Richard. Odd to meet your younger self again. It was almost, but not quite, like reading the words of a stranger – it’s a peculiar act of remembrance, with each sentence you recall a little more; a stranger who is doing things you wouldn’t necessarily approve of. Recording the book, I felt myself back in the smoke in the French countryside. Hello, Francis Orme. I wore white gloves, he said, I said.

Observatory Mansions

by Edward Carey

Once the Orme family home, now Observatory Mansions is a crumbling apartment block stranded on a traffic island. Alice Orme and her husband never leave the house, and their son Francis, who practices the art of stillness as a human statue, will touch nothing without the protection of his white gloves. Into this strange home comes new resident Alice Tapp, and her arrival will disrupt Francis’s careful routine and touch the hearts of the residents of Observatory Mansions.