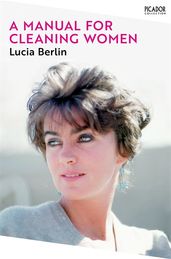

'I can’t imagine anyone who wouldn’t want to read her': Stephen Emerson on Lucia Berlin

Stephen Emerson was close friends with Lucia Berlin for 25 years, and as the editor of her posthumously published A Manual for Cleaning Women, there is perhaps no one better placed to celebrate her life and her joyful writing.

A writer of great emotional range, and remembered as 'one of America's best kept secrets', Lucia Berlin was relatively unknown during her lifetime. Stephen Emerson met Lucia in the 1970s and remained a close friend until her untimely death in 2004. The two wrote to each other for decades, and when putting the collection together in 2013 Stephen said 'her letters were by far the most painful thing to go back to.'

In 2015, he selected 43 of her quietly-acclaimed stories for publication in A Manual for Cleaning Women. While Lucia's talent was never in question, no one expected the rampant success of the collection as the book climbed The New York Times bestseller list and sold hundreds of thousands of copies worldwide. Selected as part of the new Picador Collection series, A Manual for Cleaning Women is renowned for Lucia's pioneering autofiction style and her close-up portrayal of working women.

Here, Stephen reflects on this important work and Lucia's writing life, and shares his favourite excerpts from her stories.

‘Birds ate all the hollyhock and larkspur seeds I planted . . . sitting together all in a row like at a cafeteria.' ’

— Letter to me, May 21, 1995

Lucia Berlin was as close a friend as I've ever had. She was also one of the most signal writers I've ever encountered.

The latter fact is what I want to write about here. Her extraordinary life – its color, its afflictions, and the heroism she showed especially in the fight against a brutal drinking habit.

Lucia's writing has got snap. When I think of it, I sometimes imagine a master drummer in motion behind a large trap set, striking ambidextrously at an array of snares, tom-toms, and ride cymbals while working pedals with both feet.

It isn't that the work is percussive, it's that there's so much going on.

The prose claws its way off the page. It has vitality. It reveals.

An odd little electric car, circa 1950:

‘It looked like any other car except that it was very tall and short, like a car in a cartoon that had run into a wall. A car with its hair standing on end.’

Elsewhere, outside Angel's Laundromat, where the travelers go:

‘Dirty mattresses, rusty high chairs tied to the roofs of dented old Buicks. Leaky oil pans, leaky canvas water bags. Leaky washing machines. The men sit in the cars, shirtless.’

And the mother (ah, the mother):

‘You always dressed carefully. . . Stockings with seams. A peach satin slip you let show a little on purpose, just so those peasants would know you wore one. A chiffon dress with shoulder pads, a brooch with tiny diamonds. And your coat. I was five years old and even then knew that it was a ratty old coat. Maroon, the pockets stained and frayed, the cuffs stringy.’

What her work has, is joy. A precious commodity, not encountered all that often. Balzac, Isaac Babel, García Márquez come to mind.

When prose fiction is as expansive as hers, the result is that the world gets celebrated. Out through the work, a joy radiating off the world. It is writing continuous with the irrepressibility of humanity, place, food, smells, color, language. The world seen in all its perpetual motion, its penchant to surprise and even delight.

It has nothing to do with whether the author is pessimistic or not, whether the events or feelings evoked are cheerful. The palpability of what we're shown is affirmative:

‘People in cars around us were eating sloppy things. Watermelons, pomegranates, bruised bananas. Bottles of beer spurted on ceilings, suds cascaded on the sides of cars . . . I'm hungry, I whined. Mrs. Snowden had foreseen that. Her gloved hand passed me fig newtons wrapped in talcumy Kleenex. The cookie expanded in my mouth like Japanese flowers.’

About this 'joy': no, it is not omnipresent. Yes, there are stories of unalloyed bleakness. What I have in mind is the overriding effect.

Consider 'Strays'. Its ending is as poignant as a Janis Joplin ballad. The addict-girl, ratted out by a ne'er-do-well lover who's a cook and trustee, has stuck to the program, gone to group, and been good. And then she flees. In a truck, alongside an old gaffer from a TV production crew, she heads toward the city:

‘We got to the rise, with the wide valley and the Rio Grande below us, the Sandia Mountains lovely above. 'Mister, what I need is money for a ticket home to Baton Rouge. Can you spare it, about sixty dollars?' 'Easy. You need a ticket. I need a drink. It will all work out.'’

Also like a Janis Joplin ballad, that ending has lilt.

Of course, at the same time, a riotous humor animates Lucia's work. To the topic of joy, it is germane.

Example: the humor of '502', which is an account of drunk driving that occurs—with no one behind the wheel. (The driver is asleep upstairs, drunk, as the parked car rolls down the hill). Fellow drunk Mo says, 'Thank the Lord you wasn't in it, sister . . . First thing I did, I opened the door and said, ‘Where she be?'''

In another story, the mother: 'She hated children. I met her once at an airport when all four of my kids were little. She yelled 'Call them off!' as if they were a pack of Dobermans.'

Unsurprisingly, readers of Lucia's work have sometimes used the term 'black humor'. I don't see it that way. Her humor was too funny, and it had no axe to grind. Céline and Nathanael West, Kafka—theirs is a different territory. Besides, Lucia's humor is bouncy.

But if her writing has a secret ingredient, it is suddenness. In the prose itself, shift and surprise produce a liveliness that is a mark of her art.

Her prose syncopates and hops, changes cadences, changes the subject. That's where a lot of its crackle is.

Speed in prose is not something you hear much about. Certainly not enough.

Compiling the stories for this book has been a joy in countless ways. One was discovering that in the years since her last book and her death, the work had grown in stature.

Black Sparrow and her earlier publishers gave her a good run, and certainly she's had one or two thousand dedicated readers. But that is far too few. The work will reward the most acute of readers, but there is nothing rarefied about it. On the contrary, it is inviting.

Still, the constraints of a small-press audience may, at the time, have been inevitable. After all, Lucia's whole existence occurred, pretty much, outside.

West Coast bohemia, clerical and blue-collar work, laundromats, 'meetings', stores that sell 'one-shoes', and dwellings like that trailer were the backdrop of much of her adult life (throughout which, her genteel demeanor never flagged).

And it was, in fact, 'outside' that gave her work its special strength.

From Boulder, she wrote to me (and here she alludes to her constant later companion, the oxygen tank):

‘Bay Area, New York and Mexico City [were the] only places I didn't feel I was an other. I just got back from shopping and everybody kept on saying have a great day now and smiling at my oxygen tank as if it were a poodle or a child.’

Myself, I can't imagine anyone who wouldn't want to read her.

A Manual for Cleaning Women

by Lucia Berlin

The stories in A Manual for Cleaning Women make for one of the most remarkable unsung collections in twentieth-century American fiction.

With extraordinary honesty and magnetism, Lucia Berlin invites us into her rich, itinerant life: the drink and the mess and the pain and the beauty and the moments of surprise and of grace. Her voice is uniquely witty, anarchic and compassionate. Celebrated for many years by those in the know, she is about to become - a decade after her death - the writer everyone is talking about.