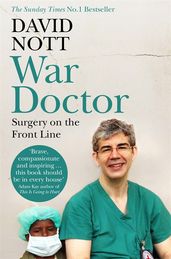

Read an extract from David Nott’s memoir, War Doctor

For more than twenty-five years, Dr David Nott has volunteered in some of the world’s most dangerous war zones. This extract from his memoir War Doctor shows the shocking reality of life on the frontline.

‘I didn’t need asking twice when, during the summer of 2012, a call came from the head office of Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in Paris, asking if I would be prepared to work in a hospital they’d set up in Syria.’ – Dr David Nott.

Dr David Nott works in London as a vascular and general surgeon for the NHS. But for the last twenty-five years, he has also volunteered as a trauma surgeon in some of the world’s most dangerous war zones and in areas devastated by natural disasters. David has carried out life-saving operations and field surgery in war-torn countries from Afghanistan to Syria. As time went on, he realised that this frontline work was not enough, and in 2015 he set up the David Nott Foundation to train other doctors in how to save lives in the most extreme of circumstances.

His memoir War Doctor is a gripping, moving and inspiring account of his time volunteering with organisations such as Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders). In these extracts from the book, he describes the shocking realities of working on the front line of the civil war in Syria.

Every now and then, at any time of day or night, we might hear the blaring of a car or pickup truck’s horn in the distance, getting louder and louder as the vehicle sped towards us with its cargo of victims. The horns acted as a siren, and we’d know to get the emergency room ready so we could assess the patients and decide who needed to go straight into theatre. On one occasion the first patient to need our help turned out to be the wife of a local bomb-maker. At that time there were a lot of small factories opening up in Atmeh that were making explosives. These were fairly crude devices and few of the people making them knew what they were doing – they were mostly working at home, making it up as they went along, and putting their own families at terrible risk.

The woman’s husband had apparently been making a bomb in his kitchen when it had detonated prematurely. The whole house was destroyed, the bomb-maker killed and his wife rushed to us with a fragment injury to her lower left leg. She was haemorrhaging significantly from the wound, which required a tourniquet to be placed immediately on the thigh.

The anaesthetist took a quick blood sample and put it through our very basic haemoglobinometer, a device which measures the red cell count in blood. It confirmed that she had a haemoglobin of 4 grams per litre – the normal amount of haemoglobin in our bodies, the stuff that carries oxygen in the blood, is between 12 and 15g/L. It was clear she had lost a great deal of blood. He quickly established her blood group and then went to get a pint of fresh blood of the right type from our dwindling supplies. Then, on the other arm, he set up a saline drip to replace some of the fluid that she had lost.

All this happened on the operating table in the dining room. The sister in charge set up the trolley with sterile drapes and instruments as the patient was given general anaesthetic. It was impossible to assess the wound properly as there was arterial bleeding, most likely from the superficial femoral artery in the leg. There was a large dressing on the top, which was acting as a local compression. I scrubbed up and prepared to operate.

One of the Syrian assistants, who didn’t speak much English, was helping to lift the leg. As I prepped the limb with iodine I asked the helper to take off the pressure dressing. The bleeding by this time had stopped, and there was a large clot overlying the wound. With the patient now draped and prepped, I started the procedure by making an incision below the tourniquet, high on the leg, so that I could get a clamp on the artery before exploring the wound. After gaining proximal control of the blood vessel I then went down to have a proper look. I tentatively put my finger into a large hole just above her knee joint, and felt an object in there which I assumed was a piece of metal – a fragment from the bomb, or maybe a bit of her house.

In this kind of scenario it is always important to go very carefully, putting your finger into the wound slowly and cautiously because there may be fractured bone which can be as sharp as shards of glass – the last thing you want is a needlestick injury without knowing the blood status of the patient. In this environment there was perhaps less concern about HIV or hepatitis, but it is a common mistake not to assume the worst.

Probing gently with my finger, it didn’t appear to be the usual jagged piece of metal or fragment but a smooth, cylindrical object. Very carefully I grabbed it with my fingers and pulled it out. I held it up to examine it, and the Syrian helper who was with me took one look and went pale. He obviously knew what I was holding, and blurted out, ‘Mufajir!’ before turning tail and leaving the room.

The anaesthetist and I looked at each other. Was I holding some sort of bomb? In that instant, I froze as I wondered what on earth I should do next. It went extremely quiet – all I could hear was the soft hiss of the ventilator pumping oxygen into the patient’s lungs. The anaesthetist shuffled away, moving across to the corner of the room behind one of the cupboards. By now my hands were shaking, I was in danger of dropping whatever it was, and I realized I had to do something. I decided to take a deep breath and walk out of the operating theatre as carefully and slowly as I could. I needed the anaesthetist to open the door for me and jerked my head in its direction to show him what I wanted, hardly daring to speak. He said to wait, as he was sure somebody was going to come very shortly – thankfully he was right, and as I deliberated for a few more seconds the door opened and in came the Syrian helper with a bucket of water. He put the bucket on the floor next to me and he and the anaesthetist ran to the safety of the next room. With my heart pounding, I carefully put the object into the bottom of the bucket, feeling the cold water seeping into the sleeve of my green scrubs, and very gingerly took it outside.

Mufajir means ‘detonator’. It was hard to tell if it was live or not. I was told later that it probably would not have killed me, but it would most likely have blown off my hand – not the end of my life, maybe, but certainly the end of my career, and at the time the two were much the same thing.

*********************************************************************************************************

Although all around us there were people coming to terms with being at war, in the house we felt pretty safe. We didn’t really take much notice of the building opposite, which seemed to be full of young men in dark combat fatigues, often carrying weapons. I suppose if I thought about it at all, I assumed it was some sort of training facility for the Free Syrian Army. We used to watch them kneeling after the mosque’s call to prayer began at around 4.30 in the morning, and knew that they could see us going about our business, too. There was something very romantic about that moment; I would lie awake on the roof, listening to the beautiful voice singing from the mosque. The air at that early hour was beautifully sweet with a crisp coldness – there was a sense of complete tranquillity as the sky gradually lightened. By seven o’clock in the morning it was too hot to lie awake on our rubber mattresses, which made it easy for us all to get up and queue for the shared toilet and shower in the building.

The sunsets were equally beautiful. More often than not the evening sky was just a vast swathe of deep blue, with the occasional wispy cloud. The sun cycled through an array of startling colours as it sank down and set between two small mountains on the horizon; it was a wonderful spectacle to watch.

On one such evening, the rest of the team had gone down to the village swimming pool. Feeling a little overweight at the time, I decided to give it a miss and go upstairs to the roof for a rest. The sunset was particularly striking, so I decided to take a photograph of it. I’d been doing these missions for many years by this time, and I knew the rule that one should never take photos on a mission with MSF. However, over the years I have always taken clinical photographs and videos for teaching purposes – with the patient’s permission, of course – often using a GoPro camera mounted on a headband. And I am very pleased that I did, because without doubt this archive of images has become a major educational tool for the teaching work I do now. And everyone took pictures, all the time – the rule, such as it was, was very widely ignored.

I set up my camera and spent quite a bit of time fiddling with the time-lapse function to get the best shot. As I was doing so I looked down into the street below and noticed someone I recognized – Dr Isa Rahman, whom I had met at the Turkey–Syria border a few weeks before. I waved to him and he waved back. He had recently qualified from Imperial College and was working with a charity called Hand in Hand for Syria, which had set up a clinic in Atmeh.

I turned back to my camera, which was on the wall overlooking the street and the buildings around us, but focused on the golden horizon far into the distance. After I’d taken a few photos I was startled by the sudden appearance of the hospital’s logistician, who burst out onto the roof having run upstairs and told me to stop immediately. He was scared and pale and could hardly speak coherently. I was oblivious to the fact that several floors below me at the entrance to the hospital were about twenty armed men who had suddenly forced their way in. They wanted my camera, thinking I had been taking pictures of them.

‘No, no,’ I protested, ‘I was just taking pictures of the sunset!’

The aggrieved men were the devout fighters from next door, who had been watching me from a distance. It emerged that they weren’t FSA at all but belonged to some jihadi group. The logistician had negotiated with them very quickly that he would get my camera and take it downstairs to show them what was on it. He told me that I must give it to him immediately – they were threatening to overrun the hospital within two minutes if they did not get the camera. I duly gave it to him and sat nervously on a chair with my heart sinking into the pit of my stomach, wondering what would happen next.

The logistician was gone for about fifteen minutes. I stood up and looked over the wall down onto the street below and caught Isa’s eye again. I motioned to him to try and see what was going on downstairs, and perhaps do something to help. He nodded to me and walked towards the hospital.

Twenty minutes after beckoning Isa, the logistician reappeared and gave my camera back, much to my surprise, as I had expected never to see it again. Fortunately there were no images of the jihadis on it, otherwise I would definitely have been taken away for interrogation and God knows what else – but despite the images being entirely innocent, the jihadis had said they wanted to take me anyway. Thankfully, Isa had eventually persuaded them to leave.

I now know that I owe Isa a great deal: shortly after this incident these young fighters abducted another MSF expat, who was held for several months. I never saw Isa again, and was very upset to find out that he was killed about twelve months later, dying from a shell injury sustained while he was working at his clinic in Idlib and which was blamed on the Syrian government forces.

I’d had any number of close shaves by this stage of my career, but this one was memorable more in hindsight – I later realized it was my first encounter with the organization now widely known as Islamic State. It has been given various names, including Daesh, an acronym of the Arabic version, but since my run-ins with its members happened in Syria, I’ll refer to it as ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and Syria).

The photo debacle would come back to haunt me in a different way, too. But at least the pictures were good.

War Doctor

by David Nott

Driven by both his desire to help others and the thrill of extreme personal danger, David Nott has become one of the world’s most experienced trauma doctors. From Sarajevo under siege in 1993 to the Syrian civil war, he has volunteered in some of the most dangerous war zones in the world. War Doctor is his extraordinary story.