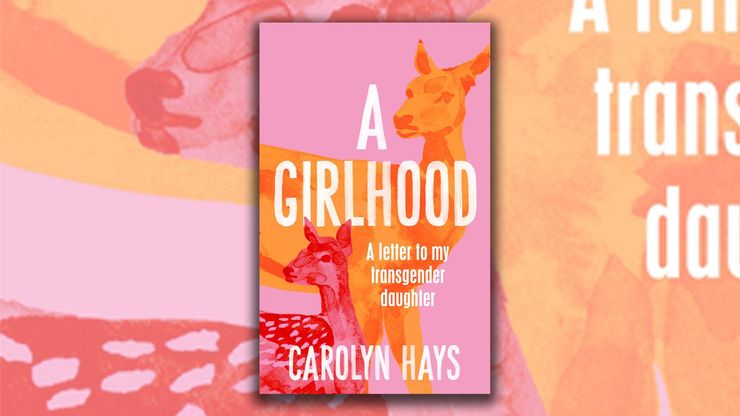

'It felt urgent': Carolyn Hays on why parents' perspectives are a vital addition to the conversation on trans rights

Carolyn Hays, author of memoir A Girlhood: A Letter to my Transgender Daughter, tells us why she wrote – and decided to publish – the book.

One ordinary day, a caseworker from the Department of Children and Families knocked on Carolyn Hays' door to investigate an anonymous complaint about the upbringing of her transgender daughter. A Girlhood is the story of what happened next, and an ode to Hays’ brilliant, brave child. Here she explains how she came to write the book and to decide, with her family, to publish it.

I get it. Another cis woman showing up in a trans space, in this case with a memoir, written by the mother (me) of a trans girl (my daughter). Why me? Why now? Why at all?

So, yes, this is going to sound like a defense. But I don’t feel defensive. I feel raw, exhausted, and, at the moment I’m writing this, embattled.

In America, this year alone, hundreds of laws have been pushed by increasingly well-organized Republican political organizations targeting trans youth – laws that take away their access to trans-related healthcare, to sports teams, and the right to use their preferred pronouns. . .

In fact, in Texas, home to thirty-nine million people, a new law targets parents who support their transgender child; they will be investigated for child abuse. So, some of these laws aim to tear children from their mothers and fathers, brothers and sisters.

This is our story. We were living in the Deep South when someone made an anonymous call and an agent for The Department of Children and Families knocked at our door to investigate us.

There I was, in the thick of raising four children, the youngest of whom was trans, and our lives were upended. I was a writer, one who’d published a lot of novels, won awards, popped on a few bestsellers lists. I knew that what I was living – its terror, love, hope, resilience, its lessons in authenticity, family, faith, community, its pungent hatred and fear – was more important and more urgent, more beautiful and heart-wrenching than any novel I could write.

For many years and for many reasons, I couldn’t write the book. But I was a diligent witness.

Some have said that the memoir should have been written by my daughter. As she’s trans and I’m not. She’s a teenager with no interest in becoming a writer. That said, she might one day be an artist. This book then becomes something she can draw from – or reject – to create her own story. This book, in the long view, is an early layer. It exists.

I started very early in her life, writing about her unique joy, her elegance – I swear, she was an elegant toddler – and her deep, abiding sense of self. Her own memories of that time are spotty. If she does choose to write her story one day, the book will help.

It’s also possible that this is the first book in which someone took notes, on this level, of a trans child’s early years. As reportage, it might be helpful, a portrait of a family in a specific time and place in transgender history.

Look, I was going to write the book anyway. Writing is how I process the world. I wasn’t going to turn it off while living something this richly complex and consuming. So the real question became: should I publish it?

When I look deeply at that question, I think, well, am I that different from other mothers who’ve written about motherhood? Shouldn’t all children have their own say, their own voice? Should mothers write memoirs at all?

As a reader, as someone keenly interested in motherhood – what’s universal and timeless as well as what’s in flux – my answer is: I sure hope so. I’m not interested in silencing voices, especially not women’s voices.

As the saying goes, love is not a pie. Neither is publishing. I hope that my memoir about raising a trans daughter opens up space for more trans writers of memoirs. We need more voices telling these stories. In America, there’s a very good chance that this book will be banned by those same Republican organizations that are so efficiently stripping civil rights from transgender kids. So, maybe I get silenced anyway.

Getting published – as some literary career move or something – is not why we, as a family, decided to go public with this memoir. We knew it would make us vulnerable all over again in ways we couldn’t predict. When we were threatened with losing custody of our daughter, it felt like a misunderstanding, a culture simply struggling to get up to speed. Now it’s part of the Republican agenda. All of this was brewing while Trump was in office, while I was writing the book, and things have gotten so much worse for families like ours.

In the end, we decided to publish the book because it felt urgent. We published it under a pen name to offer some measure of protection, one that we know might not hold. This book feels like the only thing we had to offer, the only way we could push back – with love and hope. And maybe all those years of drilling my craft by writing novels were preparing me for this memoir. I hope that, in every sentence, you feel my fear, my urgency, and my fierce love.

A Girlhood

This thought-provoking and moving memoir is an ode to Carolyn Hays' transgender daughter – a love letter to a child who has always known herself. After a caseworker from the Department of Children and Families knocked on the door to investigate an anonymous complaint about the upbringing of their transgender child, the Hays family uprooted their lives and moved away from their Republican state. But they never felt far from the hate and dear resting at the nation's core. In A Girlhood, Carolyn Hays tells of the brutal truths of being trans, of the sacrificial nature of motherhood and of the lengths a family will go to shield their youngest from the cruel realities of the world. Hays asks us all to love better, for children everywhere enduring injustice and prejudice just as they begin to understand themselves.

Carolyn Hays is a pseudonym.