Can literature help us recognize microaggressions?

Microaggressions come in many forms, from veiled racial putdowns to subtle sexual domination. Here, journalist Ali Roff Farrar explores literature's powerful ability to hold a mirror to toxic behaviours in our own relationships.

New novel Magma by Thora Hjörleifsdóttir explores the darkest corners of relationships. It follows a young woman who, in her desperation to please, is victim to imperceptible abuses that build and build until she loses her sense of self – and her perception of reality. Here Ali Roff Farrar examines the damaging nature of microaggressions, and how storytelling around this difficult topic can both heal trauma and allow readers to recognise the peril they may be in.

Death by a thousand cuts was an ancient Chinese torture technique, whereby small cuts were made to the body over a lengthy period of time, eventually resulting in death. Sounds horribly gruesome, but aside from the torture itself, one of the punishments of this technique was the idea that the body would no longer be whole in the spiritual afterlife.

If you’ve ever come across a narcissist, gaslighter or serial cheater, be it a friend, family member or romantic partner, you may have experienced a psychological version of ‘death by a thousand cuts’ first hand, in the form of microaggressions. One microaggression might be easy enough to handle and pass by, just as one cut to the body would not cause too much pain or take too long to heal. But over time, these microaggressions build and compound until they become a form of mental and emotional torture; until eventually the person becomes a fragmented, un-whole version of themselves.

‘Over time, these microaggressions build and compound until they become a form of mental and emotional torture; until eventually the person becomes a fragmented, un-whole version of themselves.’

Microaggressions are defined as ‘the everyday verbal, nonverbal, and environmental slights, snubs, or insults, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative messages to target persons based solely upon their marginalized group membership’1. A microaggression could be anything from a colleague saying ‘you actually have a great vocabulary’ to a black co-worker, to a partner saying ‘you’re going to wear that – really?’ to their significant other.

These subtle insults have a profound effect on our mental well-being. Studies have found that in racial microaggressions, people targeted suffer psychological distress, increased anxiety, depressive symptoms and post-traumatic stress disorder. They also face backlash if they speak up against the microaggressions they receive.2,3 And if we do speak up, gaslighting can begin, blaming the target for causing conflict while the perpetrator claims they didn’t mean it the way it was taken, suggesting that the target of the microaggression is the one who has the problem.

It may be easy to think ‘I wouldn’t let someone talk to me or treat me like that,’ but unfortunately the process is usually masked by a facade of friendship, professionalism, or even love, which is instated before the emotional abuse begins. It’s a lot like the fable of the boiling frog; if you drop a frog into boiling water it will jump right out, but if you drop it into cold water and slowly boil the pan, it won’t notice the steady rise in temperature and sit there until… well, you get the picture.

So how do we know we’re being gaslit, or tormented with microaggressions in our relationships? It’s a subject Thora Hjörleifsdóttir explores within a romantic relationship, in her novel Magma. Lilja is won over by an older beautiful, Derrida-quoting intellectual man. She’s so dazzled by him, she’ll do anything not to lose him, and despite his serial cheating, narcissism and emotional abuse through gaslighting, she rationalizes every wrong step he makes, every microaggression he projects towards her, every boundary he breaks. It’s easy to believe we’d never allow ourselves to stay in such a toxic relationship, but often we don’t recognize that we’re in it until it’s too late, normalizing behaviours because the alternative is too difficult to swallow.

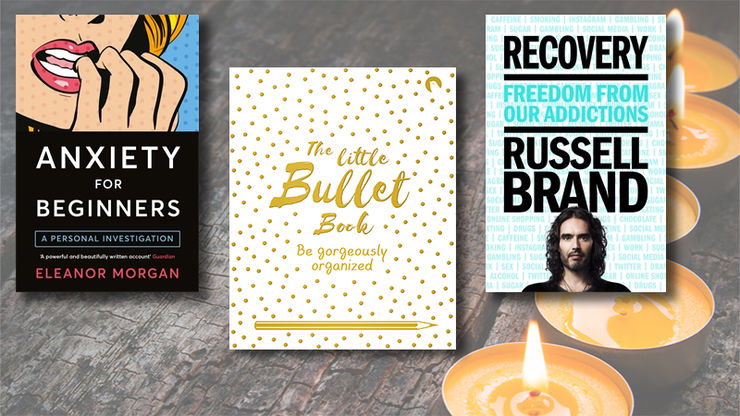

Reading about other people’s experiences, be it fictional or real life, can provide a reflective mirror for seeing ourselves within manipulative relationships. Or a tonic of realisation once we’ve freed ourselves from their toxic grip that the behaviour was not normal, and that we weren’t in the wrong, no matter how many times we were told that the confrontations, upsets and arguments were our fault.

‘Reading about other people’s experiences, be it fictional or real life, can provide a reflective mirror for seeing ourselves within manipulative relationships.’

We often also find that storytelling around trauma is used as a tool by authors to help heal past traumas they have experienced; studies have found that expressive writing can help to increase resilience, decrease depressive symptoms, perceived stress and rumination around past traumas.4

Equally, through reading these stories, we can also learn to understand and empathize with how difficult it can be for others finding themselves trapped in situations like these. ‘If, by reading ... we are enabled to step, for one moment, into another person’s shoes, to get right under their skin, then that is already a great achievement,' said Archbishop Desmond Tutu. ‘Through empathy we overcome prejudice, develop tolerance and ultimately understand love. Stories can bring understanding, healing, reconciliation and unity.’

References:

- Diversity in the Classroom, UCLA Diversity & Faculty Development, 2014

- Torres, L., & Taknint, J. T. (2015). Ethnic microaggressions, traumatic stress symptoms, and Latino depression: A moderated mediational model. Journal of Counseling Psychology

- Abdullah, T., Graham-LoPresti, J. R., Tahirkheli, N. N., Hughley, S. M., & Watson, L. T. J. (2021). Microaggressions and posttraumatic stress disorder symptom scores among Black Americans: Exploring the link. Traumatology. Advance online publication.

- Glass O, Dreusicke M, Evans J, Bechard E, Wolever RQ. Expressive writing to improve resilience to trauma: A clinical feasibility trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2019

Magma

by Thora Hjörleifsdóttir

This poetic novel, translated from Icelandic, explores the dark side of desire. Twenty-year old Lilja has fallen for an elegant intellectual older man. But he is also a narcissist and a manipulator. Blinded to his faults, and desperate to explain away his behaviour, she accepts his infidelity and machinations. Lilja is unable to escape this toxicity, until an ultimatum forces the issue, and she can choose whether to be free.