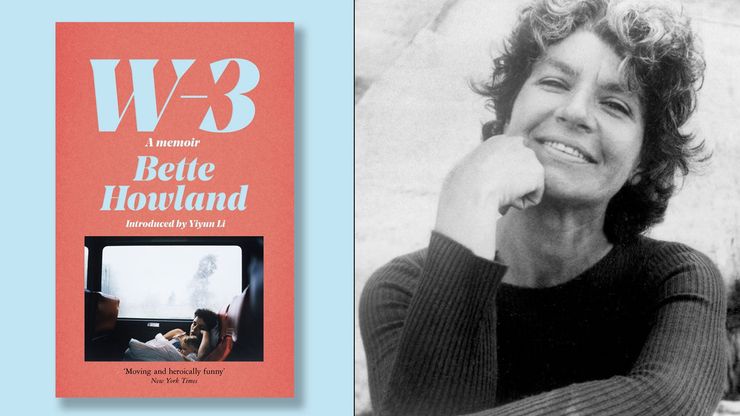

Brigid Hughes on the true story of rediscovering W-3

It's every book editor's dream to uncover a neglected masterpiece. Brigid Hughes describes the thrill of finding W-3 on the one-dollar cart.

Bette Howland's W-3 is a daring, comical and dark memoir about life on a psychiatric ward. Written in the 1960s, its concerns and compassion are timeless, but the book disappeared from view and its author slipped into obscurity. Here Brigid Hughes tells us how finding a physical copy of the book lead her to discover more about the author, who continued to write throughout her life.

Can you tell us about the day that you rediscovered Bette Howland’s W-3?

An editor is part sleuth, part subsonic listener, we search in all sorts of directions for writers and work. A few years ago, browsing in a secondhand bookstore in Manhattan, I came across a book on the one-dollar cart. W-3 by Bette Howland. It had a striking black and neon green cover, and a blurb from Saul Bellow. I opened to a page at random:

'All I knew was this: I couldn’t take it anymore, no longer could bear this burden of concealment. Things seemed bad enough without adding extra weight. I wanted to be rid of it all, all of it. I wanted to abandon all this personal history – its darkness and secrecy, its private grievances, its well-licked sorrows and prides – to thrust it from me like a manhole cover. That’s what I had wanted all along, that’s what I was trying for when I swallowed those pills – what I hoped to obliterate. That was my real need. It had at last expressed itself, become all powerful.'

How could one not want to read on?

Had you ever heard of Bette Howland before that moment?

I'd never come across her name before. So I turned to Google. There were a few glimpses of her career – a 1984 MacArthur fellowship and two other books: Blue in Chicago and Things to Come and Go, published in the late 70s and early 80s. And after that, there was really nothing, a deep silence. But it was just enough information to want to find out more. Eventually, we came across a mention of a son who was a professor in Oklahoma. We wrote to Jacob Howland, and learned that although she hadn't published another book since winning the MacArthur, she had been writing all along. An email arrived with a trove of unpublished essays, stories and letters, which we published as a portfolio in the magazine. The unanswered, or unanswerable question is why she stopped publishing after being granted the MacArthur.

Once you started reading W-3, what was it about the memoir that made you passionate about giving Bette’s work a new platform?

I’m interested in writers who have a complicated relationship with that word ‘I’. I love the way W-3 upends expectations for a memoir. The way she pays attention to the world of

W-3, the other patients, the doctors, the visitors. And how we come to know her through what she notices about others. Also, her joy and her superb humor.

Do you feel that talented women writers are at a higher risk of having their work ‘forgotten’ than men? And if so, why do you think that is?

There will always be talented writers whose work is overlooked, forgotten. Being a woman writer can sometimes be an aggravated component of it. But there are so many layers to questions about anonymity in art – what it is to seek public attention, to receive it and lose it, to flee from it, to disregard it. Bette Howland told her friend Saul Bellow that she was a rewriter not a writer, with ‘perfectionist’s disease,’ which might be one of the reasons for her literary disappearance. Anonymity isn’t always perceived as damage. For example, the writer and artist Etel Adnan said: ‘I always had a few friends who liked what I did, and that was enough. I do think I’ve kept my innocence.’

Are there any other ‘forgotten’ women writers who you feel should be household names?

There have been some extraordinary books published in the last few years, and I’m grateful to the presses that have brought attention to writers whose work had been overlooked: Kathleen Collins, Tove Ditlevsen, Lucia Berlin, Leonora Carrington. The Austrian writer Friederike Mayröcker, whose work we’ve just published, has largely not been available in English. I'm also so curious to see what their work will mean to the next generation of writers, how they might help to shape the future.

What lasting lessons do you feel you have learned from Bette’s work?

She used to keep above her writing desk notecards with quotes from favorite authors. I could fill a wall with quotes from her work, but one that I think about often comes from her story ‘Blue in Chicago’:

‘I always take books with me on buses or trains. I never read them... It seems to me that there is something immoral – because inattentive – about reading when your body is in transit. And maybe I felt even then that I should be paying attention instead. But paying attention to what?’

W-3

W-3 is a small psychiatric ward in a large university hospital, a world of pills and passes dispensed by an all-powerful staff, a world of veteran patients with grab-bags of tricks, a world of disheveled, moment-to-moment existence on the edge of permanence. Bette Howland was one of those patients. In 1968, Howland was thirty-one, a single mother of two young sons, struggling to support her family on the part-time salary of a librarian; and labouring day and night at her typewriter to be a writer. One afternoon, while staying at her friend Saul Bellow’s apartment, she swallowed a bottle of pills. W-3 is both an extraordinary portrait of the community of Ward 3 and a record of a defining moment in a writer’s life. The book itself would be her salvation: she wrote herself out of the grave.

Blue in Chicago

by Bette Howland

Also by Bette Howland, Blue in Chicago is a collection of bittersweet short stories about the lives of ordinary people and the humble grace of everyday. From city streets to the hospital to the public library to the mundane family outing, her sly humour, aching melancholy and tender insight illuminate every page.