Bridget vs the Millennials: how does Bridget Jones resonate with women 25 years on?

This year marks 25 years of Bridget Jones’s Diary. So how does the international phenomenon and, according to The Guardian, one of the defining books of the 20th century, resonate with the thirty-something women of 2021?

‘I WILL:

Stop smoking.

Drink no more than fourteen alcohol units a week.

Reduce circumference of thighs by 3 inches (i.e. 1 ½ inches each), using anti-cellulite diet.

Purge flat of all extraneous matter.

Give all clothes which have not worn for two years or more to homeless.

Improve job and find new job with potential.

Save up money in form of savings. Poss start pension also.

Be more confident.

Be more assertive.

. . .’

Reading this now, as a woman in my thirties, I am struck by three things:

- How shocking it is to read, printed in black and white, about anyone desperately wanting to reduce the size of their thighs, or any part of their body for that matter.

- How exhausted I am just thinking about this list.

- That deep down, in some ways, I can still relate.

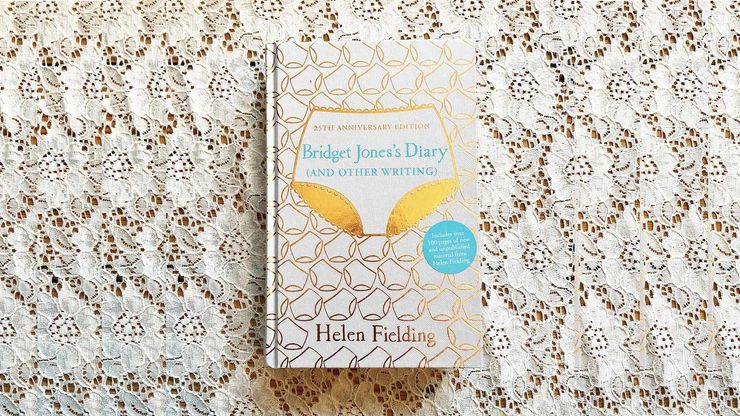

This year marks 25 years since Helen Fielding first brought the inner musings of Bridget Jones into our collective consciousness. Starting life as a series in The Independent, and blossoming into a multi-million copy number-one bestseller, Bridget Jones’s Diary fast became a literary phenomenon. It was later adapted for the silver screen, with Renee Zelweger, Hugh Grant and Colin Firth bringing Fielding's characters to life with unforgettable scenes featuring fireman’s poles and fountain-frolicking middle-class brawls that are forever immortalized in early noughties glory.

I was six years old when Bridget Jones’s Diary was first published by Picador. And I can say, hand on heart, that in my transition from childhood to womanhood I’ve watched women change the way we talk to ourselves and about ourselves. It hasn’t been easy, and if we’re honest, often it still isn’t easy, and granted, the rhetoric that swathes of the remaining proportion of the population choose to employ around women is taking a little longer to catch up, but I’m proud of the progress that we, as women, have made.

‘I can say, hand on heart, that in my transition from childhood to womanhood I’ve watched women change the way we talk to ourselves and about ourselves.’

Multiple generations are now more focused on body acceptance than rejection. We're learning to like and even love ourselves, and we are fighting for gender equality in all areas of our lives, from breaking glass ceilings to feeling safe in the knowledge that we are complete just as we are. So how then, does a calorie-counting hopeless romantic on the hunt for a partner resonate with women in their early thirties in 2021?

For many of us, the answer is . . . a little too well.

Do I feel empowered as a woman? Yes. Do I think I need a partner to complete me? Quite the opposite. Do I know that all bodies (including my own) are beautiful exactly as they are? More than anything, yes. And yet, it was only a few years ago that I too would measure certain areas of my body every week, and those thoughts I held about its perceived imperfections can still pop back up. And I know I’m not alone.

Things are changing, thanks to MeToo, AOC, Michelle Obama, Lizzo, Cheryl Strayed, Malala Yousafzai, Gina Martin, Nyome Nicholas-Williams (take a breath) . . . to name just a handful of the women and movements taking the old narrative on how we value ourselves, setting it on fire, and helping women everywhere to write their own. I’ve felt my own thought patterns change, and loved it. I’m undoubtedly more free from those old ways of thinking than I’d ever have imagined I could be. And not only does it feel great, but it’s a joy to watch the incredible women around me go through the same transition.

But (and there’s always a but), the reality is that we grew up in Bridget’s world. We grew up around – and were young and malleable around – the ‘90s and ‘00s diet culture-ridden, heteronormative, ‘other-half’-hunting world in which women were objectified and sexual harassment was considered a mere inconvenience.

The truth is, it isn’t Bridget that’s problematic – it’s the way the world made her feel that was problematic. That she should be thinner. That she should be more ‘successful’. That she should have a partner. The list goes on. The world was (and is still attempting to) ‘should’ all over women.

‘The world was (and is still attempting to) ‘should’ all over women.’

Our adolescent brains, like little balls of plasticine, were moulded by these toxic ways of thinking – just as Bridget’s was – and we’re on the long journey to rectify that. Ways of thinking and cultural programming that run centuries deep, (sadly) aren’t rewritten in a couple of decades.

Bridget holds up the effect that this had on the inner voices of many women, in a stark and brutal light. Printed clearly in black and white, it’s confronting. For the women it first touched, it showed them that they were not alone, that it was ok, wonderful in fact, to be imperfect, and that most women felt just the same.

And this was no small thing. In the recent BBC documentary, Being Bridget Jones, Candice Carty-Williams, acclaimed author of the bestselling Queenie, shared:

‘Black women are not represented in film, TV, books, like where do you find yourself? I never found myself. So I kept going back to Bridget as this person who could also mess up . . . Bridget Jones’s Diary is definitely the first place that I understood that women didn't have to be perfect. And that’s really important, and I think that now more than ever we are able to talk about that.’

For women in their thirties now, Bridget shows us how far we’ve come and why some of these feelings, despite our best efforts, can linger. And that that’s ok. It doesn't make us ‘bad feminists’ and neither is it one more thing for us to feel guilty about.

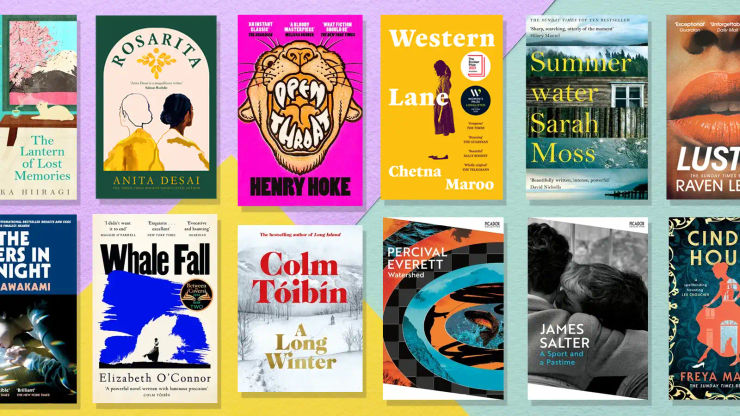

It needs to be remembered, too, that women like Helen Fielding, and other authors that show the sheer perfection in ‘imperfect’ complex women, are a huge part of this movement. Characters such Bridget Jones, Eleanor Oliphant and Raven Leilani’s magnificent millennial Edie continue to show women that their perceived flaws are actually what make them wonderful.

To conclude, millennial women continue to learn a lot from Bridget Jones. We learn not to take life too seriously. We learn not to let the patriarchy in all its forms make us feel that our bodies are in some way not enough or like some mysterious ‘other half’ is missing, and that it’s ok if some days this feels harder than others – and ultimately we learn not to fall into the same traps and start ‘shoulding’ all over ourselves. She remains the friend that we look at, and see a beautiful, successful, funny and oh-so loveable woman, that just can’t see it herself. And she remains the reminder, that that’s probably the way our friends see us, too.

And, of course, she remains the perennial reminder that life’s too short not to wear your comfy pants.

Bridget Jones's Diary

by Helen Fielding

A dazzling urban satire of modern relationships?

An ironic, tragic insight into the demise of the nuclear family?

Or the confused ramblings of a pissed thirty-something?

As Bridget documents her struggles through the social minefield of her thirties and tries to weigh up the eternal question (Daniel Cleaver or Mark Darcy?), she turns for support to four indispensable friends: Shazzer, Jude, Tom and a bottle of chardonnay.

Welcome to Bridget's first diary: mercilessly funny, endlessly touching and utterly addictive.