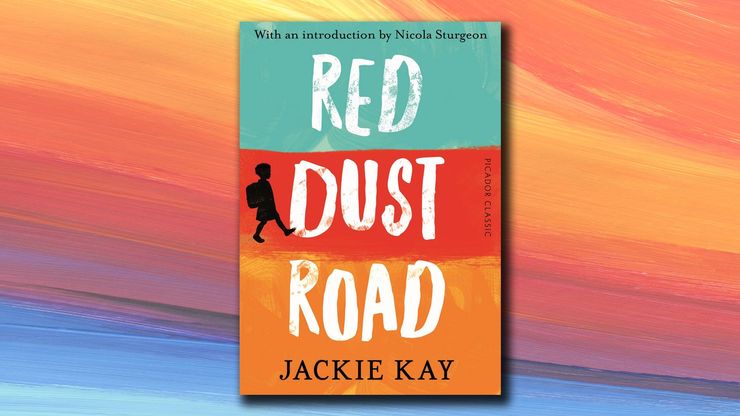

An extract from Jackie Kay's Red Dust Road

Red Dust Road is a heart-stopping story of parents and siblings, friends and strangers, belonging and beliefs, biology and destiny.

In her deeply moving book, Red Dust Road, Jackie Kay describes an encounter with a stranger on a train who reads her ancestry in her features. Read on for an extract from the book and the poem that the chance meeting inspired.

'Just one article and he'll be on the net,' she said. I was amazed that it had never occurred to me to Google my father! Over the years I'd thought of getting in touch with Aberdeen University's student records. I'd thought of writing to the Nigerian Embassy who supported the students who came to Scotland in the sixties. I'd been told by various Nigerian friends that, with a surname, he should be easy enough to trace; surnames give you a rough idea of the part of Nigeria people are from.

Years earlier, I'd been on a night train from London to Manchester after having done a poetry gig. (It's funny how we poets call readings gigs, really sad and pathetic, just to pretend we are pop stars. We meet each other on the road and say, 'Done any good gigs recently?' 'Yes, Milton Keynes Central Library.') A black man, sitting opposite me, looked at my face and said suddenly 'I bet you are an Igbo. Igbo - definitely!' It was such a striking experience that I wrote a poem about it.

I discovered the man on the train was right. My father was an Igbo.'

Pride

When I looked up, the black man was there,

staring into my face,

as if he had always been there,

as if he and I went a long way back.

He looked into the dark pool of my eyes

as the train slid out of Euston.

For a long time this went on

the stranger and I looking at each other,

a look that was like something being given

from one to the other.

My whole childhood, I'm quite sure,

passed before him, the worst things

I've ever done, the biggest lies I've ever told.

And he was a little boy on a red dust road.

He stared into the dark depth of me,

and then he spoke:

'Ibo' he said. 'Ibo, definitely.'

Our train rushed through the dark.

'You are an Ibo!' he said, thumping the table.

My coffee jumped and spilled.

Several sleeping people woke.

The night train boasted and whistled

through the English countryside,

past unwritten stops in the blackness.

'That nose is an Ibo nose.

Those teeth are Ibo teeth,' the stranger said,

his voice getting louder and louder.

I had no doubt, from the way he said it,

that Ibo noses are the best noses in the world,

that Ibo teeth are perfect pearls.

People were walking down the trembling aisle

to come and take a look

as the night rain babbled against the window.

There was a moment when

my whole face changed into a map,

and the stranger on the train

located even the name

of my village in Nigeria

in the lower part of my jaw.

I told him what I'd heard was my father's name.

He told me what it meant,

something stunning,

something so apt and astonishing.

Tell me, I asked the black man on the train

who was himself transforming,

at roughly the same speed as the train,

and could have been

at any stop, my brother, my father as a young man,

or any member of my large clan,

Tell me about the Ibos.

His face had a look

I've seen on a MacLachlan, a MacDonell, a MacLeod,

the most startling thing, pride,

a quality of being certain.

Now that I know you are an Ibo, we will eat.

He produced a spicy meat patty,

ripping it into two.

Tell me about the Ibos.

'The Ibos are small in stature

Not tall like the Yoruba or Hausa.

The Ibos are clever, reliable,

dependable, faithful, true.

The Ibos should be running Nigeria.

There would be none of this corruption.'

And what, I asked, are the Ibos faults?

I smiled my newly acquired Ibo smile,

flashed my gleaming Ibo teeth.

The train grabbed at a bend,

'Faults? No faults. Not a single one.'

'If you went back,' he said brightening,

'The whole village would come out for you.

Massive celebrations. Definitely.

Definitely,' he opened his arms wide.

'The eldest grandchild - fantastic welcome.

If the grandparents are alive.'

I saw myself arriving

the hot dust, the red road,

the trees heavy with other fruits,

the bright things, the flowers.

I saw myself watching

the old people dance towards me

dressed up for me in happy prints.

And I found my feet.

I started to dance.

I danced a dance I never knew I knew.

Words and sounds fell out of my mouth like seeds.

I astonished myself.

My grandmother was like me exactly, only darker.

When I looked up, the black man had gone.

Only my own face startled me in the dark train window.

Red Dust Road

From the moment when, as a little girl, she realizes that her skin is a different colour from that of her beloved mum and dad, to the tracing and finding of her birth parents, her Highland mother and Nigerian father, Jackie Kay’s journey in Red Dust Road is one of unexpected twists, turns and deep emotions. She takes a trip to Nigeria in search of her birth father in this warm but unsentimental journey into nature, nurture and identity.

This Picador Classic edition comes with an introduction by the First Minister of Scotland, Nicola Sturgeon.