Misogyny & the menopause: A brief history

Health journalist and co-author of Cracking the Menopause Alice Smellie reveals the shocking ways in which menopause has been perceived and discussed throughout history, from the suspicion of the Middle Ages to the advent of 1960s pharmaceutical treatments.

Despite thousands of years of medical advancements, the female-led conversation around the menopause seems to have only just begun, after centuries of bizarre declarations and false findings from male academics.

In Cracking the Menopause, Mariella Frostrup and Alice Smellie call for this powerful life change to be 'renovated and elevated'. Featuring case studies from women in every walk of life and all stages of their menopause journey, this important work is designed to equip you with vital knowledge and open up the conversation about an urgent topic that half the population will experience.

In this piece, Alice Smellie looks back in time at the misogyny that has shaped narratives around the menopause, and wrests apart the untruths that have been attached to menopausal women since the thirteenth century.

Medieval Madness

One of the most fascinating elements of writing Cracking the Menopause was reading the many historical documents and books which referenced menopause, most of which were either derogatory or just downright insulting.

Travelling through our bloody – literally – history, in the Middle Ages our inability to get rid of what was considered toxic blood meant that menopausal women were seen as bubbling cauldrons of poisons.

The thirteenth-century German philosopher and scientist, Albertus Magnus, whose day job was ‘German Catholic Dominican Bishop’, wrote a dark tome called De Secretis Mulierum (Women’s Secrets). This cheery book was filled with dark insights about, 'The retention of menses’.

Magnus – and I think it’s fair to suggest that he wasn’t exactly a jolly family man – believed that older women were poisonous and dangerous, with the ability to kill children just by looking at them. Sometimes, when a teen is being particularly infuriating, and begging to stay on at a party, for example, it would be a useful threat. ‘Midnight, or I come in and LOOK at you.’

What a typical menopausal reference. The moment it’s remotely interesting to medics, academics and men – usually the same thing – it’s evident that it’s judged to be a scourge rather than a liberation. Typically, his flagrant inaccuracies didn’t stand in the way of his career success; Magnus was later canonized as Saint Albert the Great, patron saint of the natural sciences.

The Age of Advancement?

By the middle of the nineteenth century, doctors pretty much linked anything menstrual, ovary or womb-themed with madness and hysteria, especially if you were drawing near to the end of your cycles. At no time were women more likely to become unstable, the men said grimly, than around this time. As you lost your one useful purpose, you also lost your marbles and even your health.

‘Insanity frequently occurs at the change of constitution,’ agreed the obstetrician and writer W. Tyler Smith in his 1849 article, 'The Climacteric Disease in Women'. ‘I have no doubt that it is often owing to the climacteric paroxysms. Each paroxysm is a distinct shock to the brain, leaving behind it peevishness, irritability of temper and eccentricity.’

As well as being insane and ill, once menopause had us in its grip, we were ugly. In 1882, the English doctor Edward Tilt said that you could spot a menopausal woman a mile off. ‘The complexion is pale or sallow, or there may be a drowsy look, or the dull, stupid astonishment of one seeking to rouse herself to answer a question.’ There’s also, he said, a tendency to sprout hair on the upper lip and chin (the latter a fair point, especially if you add testosterone to your HRT cocktail!).

Cure (or kill)

Because it was a disease, menopause needed to be cured. Some of the therapies were foul – and far more dangerous and disconcerting than any hot flush or sleepless night.

For example, W. Tyler Smith liked to get his hands dirty, and he particularly delights in describing with eye-watering and vampiric glee the benefits of bloodletting from the womb.

Without going into too much detail, suffice it to say that this involves applying three or four leeches to the cervical area. Further joyful solutions included ice in the vagina and cold-water injections into the rectum.

Edward Tilt also recommended some quite eye-watering solutions for our failing bodies. ‘Camphor . . . seems to correct the toxic influence which the reproductive system has on the brain of some women.’ Tilt also talks lightly of the application of leeches to the anus or ears. Or six to eight – count ’em – leeches on the perineum.

American surgeon Andrew Currier advocated simple problem-solving in the 1890s by whipping out the ovaries and causing artificial menopause. There were plenty of such unnecessary-sounding operations performed, with an overwhelming air of ‘might as well give it a go’ about the whole thing.

Incidentally any patient experience of vaginal leeching (good or bad) remains unrecorded. I couldn’t find any ‘tried and tested’ reviews available from those subjected to W. Tyler Smith’s treatments, but I suspect he would have fared pretty poorly on Instagram likes.

From a twenty-first-century female point of view, the very thought of most of these ‘cures’ would be enough for me to say quite firmly that I was just fine, free of all my feminine wiles (or should that be viles?), and promise to live out my remaining years very quietly, under the radar, so as not to disturb men any further with my offensive presence.

Hats off to HRT

And then in the mid-twentieth century we struck gold. It’s over to the States and HRT (hormone replacement therapy) for all. The time had come to hold onto your bonnets and stay pretty, little ladies! Menopause was a deficiency disease, but no worries, as long as you take the drugs. In the swinging Sixties, HRT was all the rage, and in 1966 the American gynaecologist Robert A. Wilson, MD, who published a book called Feminine Forever, told us why. His unequivocal viewpoint . . . that ladies needed to remain young and fun, or they’d lose their husbands, and quite right too.

Wilson, no great shakes in the looks department himself, since we’re chucking insults around, charmlessly refers to the menopausal state as ‘living decay’, with some quite staggering claims. The menopause is apparently ‘curable’ and also ‘completely preventable’; and why wouldn’t you want to stop it in its tracks, as ‘the unpalatable truth must be faced that all post-menopausal women are castrates’. That’s right. We’re men without testicles. Not women.

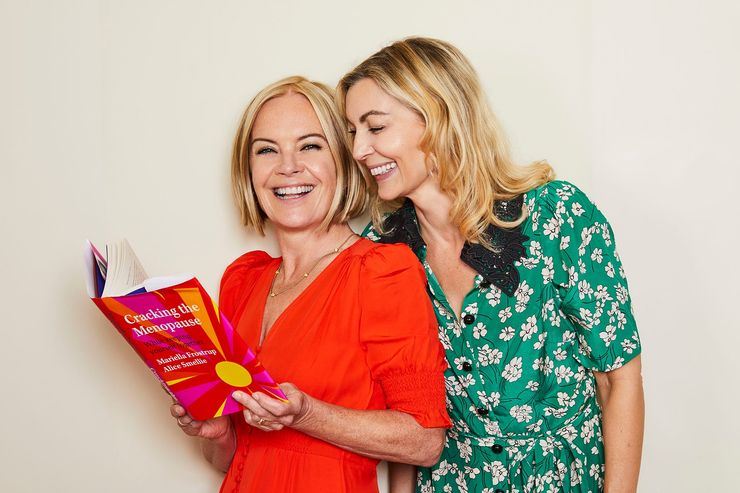

In Cracking the Menopause, straight-talking broadcaster Mariella Frostrup joins forces with health journalist Alice Smellie to deliver all the information you need. Full of characteristic wry humour, Mariella details her own journey through the menopause with the help of the latest science, advice from experts, and a few tongue-in-cheek illustrations.

Image credit: Kate Martin

Cracking the Menopause

by Mariella Frostrup

It's time to start talking about the menopause. Straight-talking broadcaster Mariella Frostrup joins forces with health journalist Alice Smellie to deliver all the information you need. Full of characteristic wry humour, Mariella details her own journey through the menopause with the help of the latest science, advice from experts, and a few tongue-in-cheek illustrations.

Featuring case studies from women in every walk of life and all stages of their menopause journey, Cracking the Menopause provides an informative source of wisdom and enlightenment that separates the myths from the reality and offers expertise, hope and advice.