Lifestyle & Wellbeing

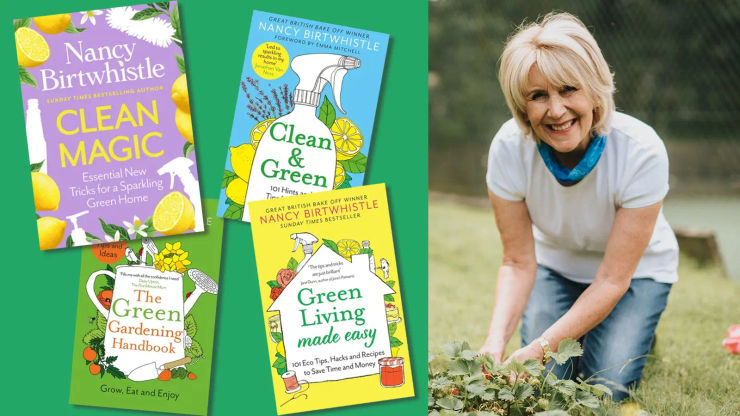

Pure Magic: Nancy Birtwhistle shares her eco-friendly cleaning and gardening tips

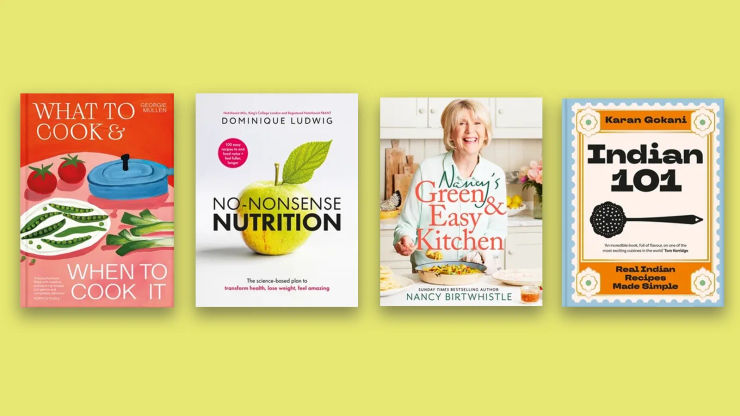

The best cookbooks for every occasion

10 ways to make your life a little bit better in 2026

Healthy in One example asset page

The best self-care and self-help books to read right now

28 best mental health books to read in 2026

Pinch of Nom books in order: a complete guide

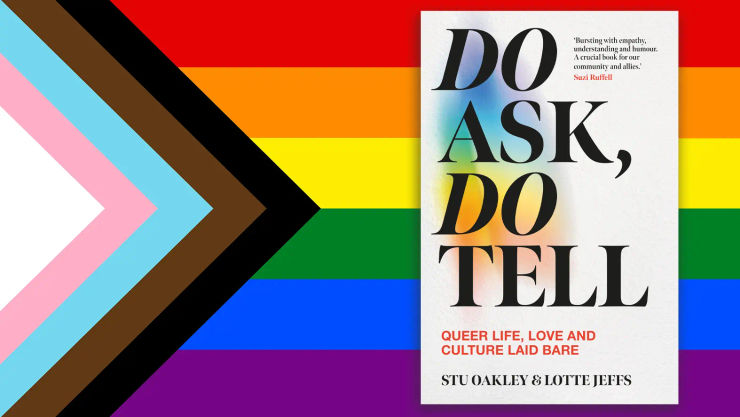

‘There is a seldom-discussed risk when it comes to queer dating – inadvertently being the subject of someone’s little experiment.’

Everything you ever wanted to ask about queer life (but didn’t want to get wrong)

When should I see a doctor? Periods: what’s normal, what’s not

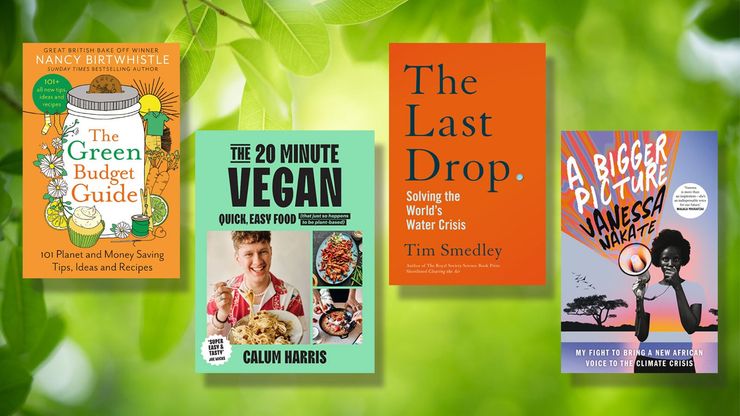

The best books on sustainable living

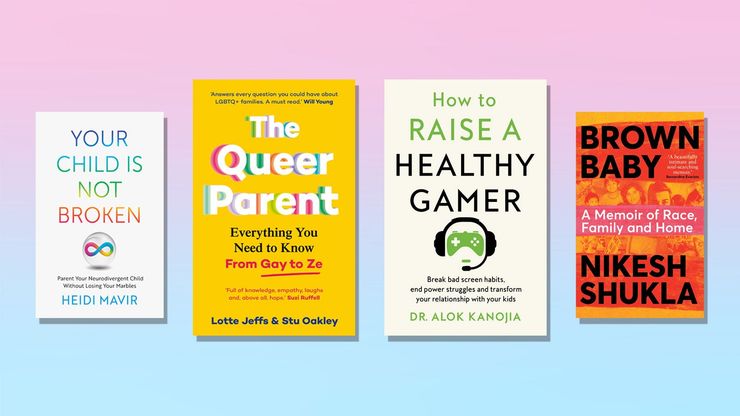

17 best parenting books for 2025