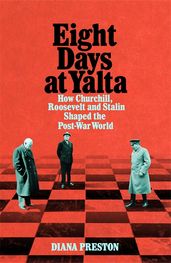

How Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin shaped the post-war world

The outcome of the Yalta Conference affected events throughout the 20th century and shaped modern history. Could the consequences have been any different?

The Yalta Conference took place between 4 and 11 February 1945, eight days in which Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin debated the new world order – making decisions on how Germany should be governed after its defeat, where borders should lie in eastern Europe and how the Soviet Union should enter the war against Japan. The outcome of the conference had wide-ranging implications for the twentieth-century world, from the Korean War to Britain’s relationship with the European Union.

In her meticulously researched and vividly written book, Eight Days at Yalta, historian Diana Preston chronicles eight days that created the post-war world. But, she asks here, could the outcome have been any different?

Amid the convulsions of a world war, with millions of displaced persons on the move, between 4-11 February 1945 in the Crimean resort of Yalta the frail Roosevelt, exhausted Churchill and their determined host and war-time ally Stalin debated the new world order.

Over eight days of bargaining, bombast and occasional bonhomie – fuelled by Soviet caviar, vodka and champagne – the three agreed the endgame of the war against Germany and how it should be governed after its defeat. They also decided the constitution of the nascent United Nations, Soviet terms for entering the war against Japan and spheres of influence in and new borders for Eastern Europe (in particular Poland) and the Balkans. In the final hours of the conference, the three leaders signed a Declaration on Liberated Europe affirming the right of newly liberated countries to self-determination and democracy, after which Stalin boarded the armoured train that would carry him 1,000 wintry miles back to Moscow. As they too departed, Roosevelt and Churchill convinced themselves they could trust the Soviet leader, and would in the next days tell their peoples so.

However, Stalin would not live up to his promises on Eastern Europe. Just three months later, soon after Roosevelt’s death, Churchill wrote gloomily to the new US president Harry Truman of ‘an iron curtain’ now being ‘drawn upon [the Soviets’] front’, adding ‘this issue of a settlement with Russia before our strength has gone seems to me to dwarf all others.’

Yet it was already too late. A further conference, this time in Potsdam outside Berlin in summer 1945, failed to persuade Stalin to honour the Yalta agreements. The US and UK watched helplessly as the Soviet Union tightened its grip on the countries of Eastern Europe, including Poland, for whose freedom Britain had gone to war and for whom Churchill and Roosevelt had fought hard at Yalta.

Because the Cold War began so soon afterwards, Yalta has become a byword for failure and broken promises. In 2005, President George W. Bush called Yalta ‘one of the greatest wrongs of history … Once again, when powerful governments negotiated, the freedom of small nations was somehow expendable.’ However, could the outcome really have been greatly different?

By the time of Yalta, Soviet armies occupied much of Eastern Europe and were within fifty miles of Berlin. The situation in which Roosevelt and Churchill found themselves has analogies to that of the Crimea today, annexed by Russia, and that of the eastern Ukraine where divergent ethnicities dispute the borders.In both cases, Western leaders have few viable sanctions against Russia other than moral pressure. Stalin was rightly confident in his belief that, ‘whoever occupies a territory also imposes on it his own social system. Everyone imposes his own system as far as his army has power to do so. It cannot be otherwise.’

Churchill and Roosevelt’s negotiating position would have been considerably improved had the conference not been twice postponed from the originally proposed late summer of 1944 at Roosevelt’s urging – once for his presidential election campaign and then for his inauguration in January 1945 for a unique fourth term. In mid-1944, Soviet troops occupied much less of Eastern Europe and Stalin’s position at Yalta would have been correspondingly weaker.

The discussions at Yalta about Poland, already now occupied by the Red Army, provided a brutal demonstration of Stalin’s philosophy. Intent on securing a cordon sanitaire of satellite states around the Soviet Union, Stalin and his foreign minister Molotov – known as ‘Stone Arse’ by the Western delegates for his ability to sit for hours conceding nothing – repeatedly frustrated Churchill’s and Roosevelt’s attempts to secure a representative government and fair democratic elections. Poland would not become ‘mistress in her own house and captain of her own soul’– as Churchill put it – for nearly half a century.

Yet even in February 1945, Roosevelt might have made better use of American economic muscle. Stalin believed that ‘the most important things in this war are machines’ and that the US was ‘a country of machines … Without the use of those machines, through Lend-Lease, we would lose this war.’ Had Roosevelt threatened to withdraw Lend-Lease – the arrangement by which the US supplied her allies with equipment on a ‘use now, pay later’ basis – he might just have secured better protection for millions in Eastern Europe.

Other aspects of the conference in what Churchill called ‘the Riviera of Hades’ still resonate. Neither Roosevelt nor Churchill mentioned to Stalin the Manhattan A-bomb project which was gathering momentum. However Stalin knew about it through his spies and saw the Western silence as an example of their mistrust. Had Roosevelt had more faith in the nascent project, he might have been less eager to agree terms with Stalin for the Soviet Union to enter the war against Japan and to invade Japanese-occupied territory – something he believed essential to preserve the lives of millions of US troops likely to be lost in an invasion of the Japanese home islands.

As it was, the first successful atomic bomb test came just five months after Yalta, demonstrating the diminished need for Soviet assistance, not least to Stalin to whom at Potsdam Truman disclosed the test and who, as a consequence, brought forward his plans for Soviet troops to move into Japanese-occupied Manchuria and Korea. Without the Soviet advance to the 38th parallel in Korea – and to a lesser extent the Soviet occupation of the Kurile Islands and Sakhalin agreed at Yalta – the Korean War would probably not have happened. Korea might today be united and democratic and many of the still continuing tensions in the region might not have arisen.

Another, if perhaps less obvious, area where the Yalta Conference still resonates is the UK’s relationship with France and thereby the European Union. The resentment of General de Gaulle, Head of the French Provisional Government, at his exclusion from Yalta persisted for the rest of his life and resulted in his deep distrust of what he saw as Anglo-American hegemony, for example in keeping atomic weapons information from France as well as from the Soviet Union. His distrust led not only to France’s withdrawal from NATO’s active command structure in 1966 but also to his absolute veto against Britain’s entry into the European Community in 1963 and 1967. In 1963 he asserted ‘L’Angleterre ce n’est plus grand chose’ – ‘England isn’t much any more’. Arguably, had Britain been involved in the European Union at an earlier date, it might have had a greater influence on its development and just perhaps meant that the 2016 Brexit referendum might never have been called and – even if it had – that the result might have been different.

Yet the Yalta Conference had its successes, not least the strategy for defeating Hitler and ending the war in Europe and the agreement on the structure of the United Nations which held its first meeting just two months later. Although the veto arrangements for the Security Council decided at Yalta would hamper its attempts at mediating between the great powers, the UN has had some success in peace-keeping elsewhere.

Controversy continues as to whether the price Churchill and Roosevelt paid at Yalta for peace and stability in western Europe was too great. Yet in February 1945, though they might have played their cards a little better, neither leader held the strongest of hands. Reflecting on the conference in its immediate aftermath, Roosevelt told an adviser privately, ‘I didn’t say the result was good. I said it was the best I could do’ – a view Churchill shared. Even today this does not seem an unjust verdict.

Eight Days at Yalta

Diana Preston’s scrupulously researched book, Eight Days at Yalta, recounts the intense historical drama of the Yalta Conference and its outcomes. From Roosevelt’s determination to bring about the end of the British Empire to Stalin’s territorial ambitions, these events created the post-war world.