Margaret Dickinson on Sheffield’s ‘buffer girls’

Bestselling author Margaret Dickinson tells us about the women of Sheffield's cutlery industry in the 19th and 20th century, who inspired her latest novel, The Buffer Girls.

Bestselling author Margaret Dickinson tells us about the women of Sheffield's cutlery industry in the 19th and 20th century, who inspired her novel, The Buffer Girls.

From the late 1800s, many women worked in Sheffield's cutlery trade doing a wide variety of jobs, mostly unskilled or semi-skilled, but the most famous of these were the ‘buffer girls', who polished the cutlery.

They would start aged fourteen or fifteen as ‘errand lasses', arriving at work before the buffer girls, who usually worked on piece rates. They would mix together a quantity of sand and oil and share it out to each buffer's workbench. This was used in the polishing process. They would probably have to light the fire in the stove, sweep the workshop and, throughout the day, deliver work to the buffer girls under the direction of the ‘buffer missus' – the woman in charge of the workshop. They would also run errands for the women, even doing their shopping for them. In spare moments, an errand lass would learn the trade and would eventually be trained to work as a buffer. The women dressed in ‘buff-brats'; a white overall worn over an old dress. They wore a triangular red rag over their hair and a red neck rag, and used brown paper or newspaper over the buff-brats and around their legs to catch the worst of the flying oily sand.

Many worked in a buffing workshop as part of a large firm overseen by a buffer missus, but some set up their own small, independent workshops in rented premises and bought their own machinery, which would probably be second-hand. They would employ a few other women, who would need to be skilled in several processes rather than in just one. These women were like ‘little mesters'; self-employed craftsmen who worked for themselves or as ‘outworkers' for large firms. Whether they realized it at the time – for such work was commonplace in the city – they were undoubtedly shrewd businesswomen.

They often worked long hours as well as caring for a family, for, despite the dirty job, they were very house-proud. And they supported one another in times of hardship.

But they were a merry bunch; they sang all day at their machines. At dinnertime, they would often go into the city centre, still dressed in their grubby working clothes, walking arm in arm, laughing and joking. They enjoyed visits to the music hall or the picture palace, a summer trip to the seaside and Christmas parties.

Before 1939, female union membership was sparse, but more women joined during the Second World War, no doubt looking for support when the men were away. It wasn't until after the war that improvements were made to working conditions. Despite the hardships, or perhaps because of them, the buffer girls were legendary; they were spirited and spoke their minds, but they were kind-hearted, too. They took pride in their work and, in turn, became the pride of the city famous for its cutlery industry, in which they undoubtedly played a huge part.

If you are intrigued to learn more about the real buffer girls, read Gill Booth's wonderful book, Diamonds in Brown Paper, published by Sheffield City Libraries, or visit the Kelham Island Museum in Sheffield.

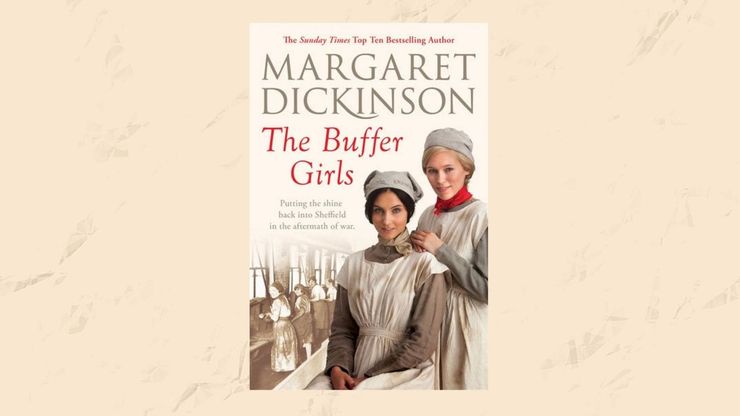

The Buffer Girls

by Margaret Dickinson

It is 1920 in the Derbyshire dales. The Ryan family are adjusting to life now that the war is over. Walter has returned home a broken man and so it falls to his son and daughter, Josh and Emily, to keep the family candle-making business going.

The Ryan children grew up with Amy Clark, daughter of the village blacksmith, and Thomas 'Trip' Trippett, whose father owns a cutlery business in Sheffield. Romance blossoms for Josh and Amy while Emily falls in love with Trip, but she is unsure if the feeling is mutual. Martha Ryan is fiercely ambitious for her son and so she uproots her family to Sheffield, but all Josh wants is to continue the family business and marry Amy. As the Ryans do their best to adapt to city life, their friendly neighbour, Lizzie, helps Emily find employment as a Buffer Girl polishing cutlery at a local factory.

It turns out that it is Emily who is best equipped to forge a career but, as time goes on, problems and even dangers arise that the Ryan family could not possibly have foreseen.