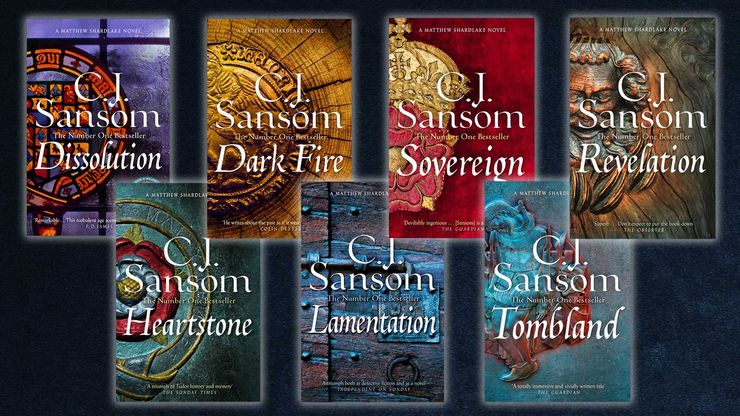

C.J. Sansom on Heartstone and the Mary Rose

C. J. Sansom discusses why he chose to base his fifth Shardlake novel, Heartstone, aboard Henry VIII's warship the Mary Rose.

As Henry VIII's warship Mary Rose is unveiled in Portsmouth 471 years after it first sank into the Solent, we revisit C. J. Sansom's piece on the ship central to his fifth Shardlake novel, Heartstone.

Image Credit: Geoff Hunt Sailing ©PPRSMA

When I conceived the idea of a Shardlake novel where the threads of the story would converge on board Henry VIII’s warship Mary Rose as it prepared to sail out to do battle with the approaching French fleet in July 1545, I had little idea of the sheer scale of the material that was available in Portsmouth.

I knew of course that the ship had sunk while sailing out to meet the French warships on a hot July day and that the lower half of the ship had been preserved, the silt at the bottom of the Solent serving to limit decay.

I had seen, on television, the remains of the ship lifted from the seabed in 1982, and had visited it in Portsmouth – visible only through a window at a distance, for the timbers had to be sprayed constantly with water and chemicals to preserve them.

Having written the first, outline draft of the story, I visited the Mary Rose Museum again and made contact with its expert and devoted staff. They opened a whole new world to me, the world not just of the ship in all its extraordinary and intricate detail – for Tudor warships were at the cutting edge of technical and engineering knowledge – but, and, for me even more compellingly, the world of the men who served on board the ship.

For, along with the Mary Rose, divers working in the often murky and dangerous conditions have also recovered from beneath the silt, over the years, probably the best collection of Tudor artefacts anywhere in the world.

Their range is extraordinary – the clothes and shoes the soldiers and sailors wore, their weapons, their armour, their bowls and knives, the remains of the food they ate, rosaries and dice, longbows and platters. And the remains of the men themselves, all suddenly drowned as the Mary Rose foundered.

We know from the study of their skeletons that they were mostly in their twenties, strongly built, only a little shorter than people today, and that a surprising number were foreign recruits. We know a lot of them would have had toothache from untreated dental problems, and that some had rickets, probably from lack of food during the time of the ‘Great Dearth’ of 1527–8. That winter, following a very bad harvest, many of England’s poor were reduced to semi-starvation. (Their King, meanwhile, was preoccupied with trying to obtain an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon.) We know that one of the men had a problem with his foot, perhaps a bunion, and had made a cut in his shoe to ease the pain.

This extraordinary level of detail about the lives of the men of the Mary Rose, from officers to ordinary soldiers and sailors, gave me a fascinating, not to say daunting opportunity. Here was a chance to people a dramatic historical setting with an extraordinary wealth of intimate detail about the daily lives of the people involved.

I had written about a spectacular Tudor event before when I described Henry VIII’s Progress to the North in 1541 in Sovereign. But little was known about the detail of life on the Progress, so I had to imagine much. Here I had not only the remains of the ship itself but all the recovered material.

My decision to put a company of archers at the centre of the story means that the soldiers’ rather than sailors’ artefacts get a disproportionate share; but to use all the material available at The Mary Rose Museum would take a whole novel sequence.

But there was so much that I was able to use; Sir Franklin Giffard’s elaborate clothing, the woollen jerkins of the men, their shoes, their longbows, their elaborate knives decorated with carvings, their food in camp, the earscoops and nit-combs and coins, all come from the Mary Rose collection, as do the descriptions of life on board, ranging from the tiny set of dice used by the sailors (so many of the soldiers’ and sailors’ personal possessions, from dice to prayer books, were very small, to allow them to be carried about on board ship and in camp) to the huge brick ovens in the bowels of the ship where the food was cooked.

The new Museum is now open and proving a huge success. Fundraising continues in order to develop research and educational facilities in what is the most brilliant museum I have ever seen.

You can find out more about The Mary Rose Museum and support the conservation of the Mary Rose and her collection of artefacts here.

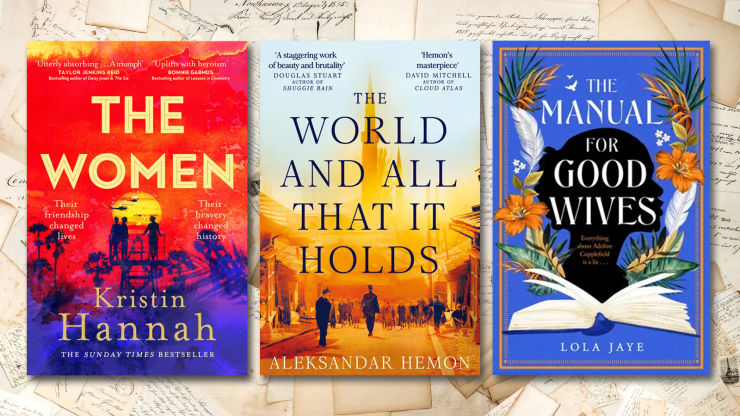

Heartstone

Shardlake goes to war in the fifth historical mystery in the compelling series.

England, 1545: England is at war. Henry VIII's invasion of France has gone badly wrong, and a massive French fleet is preparing to sail across the Channel. As the English fleet gathers at Portsmouth, the country raises the largest militia army it has ever seen. Meanwhile, Matthew Shardlake finds himself involved in not one, but two intriguing investigations. Events will converge on board one of the King's great warships, primed for battle in Portsmouth harbour . . .