This is Going to Hurt: your questions answered

All your questions about This is Going to Hurt answered.

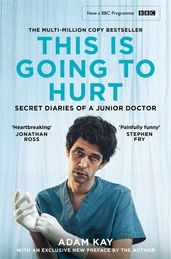

A multi-million copy bestseller by Adam Kay adapted into a BAFTA-nominated BBC comedy-drama starring Ben Whishaw, This is Going to Hurt has profoundly influenced how we view the NHS and its doctors. Taken from Kay's diary entries during his time on the obstetrics and gynaecology ward, this no-holds-barred account of his time on the NHS front line is painfully (but also hilariously) unforgettable, whether experienced on the page or the screen.

Here, we answer all of your questions about the book and TV show. Warning: there are spoilers!

Is This is Going to Hurt based on a true story?

In short, yes. The book is an edited collection of Adam Kay's diary entries from his time working for the NHS, with anecdotes from his time both on and off the ward. The TV adaptation is a fictionalised version of Kay's lived experiences.

How true is the This is Going to Hurt TV series to the book?

While a lot of the stories and experiences from the book also occur in the TV series, such as the haemophilia/ hermaphrodite mix-up and some unnecessary panic caused by a trapped catheter tube, some aspects of Kay's time on the wards have been changed for the show and new storylines have been added.

For example, one of the central narrative threads of the TV show revolves around Kay being reported to the General Medical Council, which doesn't happen in the book. Similarly, there are characters in the TV show who either don't appear in the book at all, or feature only briefly. The biggest difference between the book and the TV series is the former doesn't feature trainee doctor Shruti Acharya, whose storyline broke the hearts of many watching the show.

Is Shruti Acharya based on a real person?

Shruti Acharya is a central character in the BBC's adaptation of This is Going to Hurt. However, she isn't in the book, nor is she based on a real person. Her character was created for the show to highlight the pressures and strains put on doctors and the importance of protecting their mental health.

Is there a season two of This is Going to Hurt?

Sadly, we're not aware of any plans for season two of the TV show. However, if you can't get enough of This is Going to Hurt, the tie-in edition of the book includes an exclusive preface from Adam Kay and other bonus content.

If you're one step ahead and have already read the book, discover Twas The Nightshift Before Christmas, Kay's festive hospital diaries and a love letter to all those who spend the Christmas season on the front line.

Do Adam and Harry/ H end up together in This Is Going to Hurt?

Adam's partner Harry captured the hearts of many in the TV adaptation of This is Going to Hurt. The series finishes with both Adam and Harry declaring they miss each other, but ultimately realising their lifestyles are no longer compatible. They part on amicable terms with Adam deciding he is not ready to leave medicine behind just yet.

In contrast, the book ends when Adam decides to leave his job following a traumatic delivery. Adam does refer to having a partner in the book, known only as H, but they are mentioned only sporadically. However, much like the series, it is implied their relationship ends due to the strains and pressures Adam is under at work.

Where can I watch This Is Going to Hurt?

The TV adaptation of This is Going to Hurt was broadcast in February 2022. You can watch the entire series on iPlayer.

This is Going to Hurt

by Adam Kay

97-hour weeks, life and death decisions, a constant tsunami of bodily fluids, and the hospital parking meter earns more than you. The life of a junior doctor may not sound funny, but Adam Kay’s memoir certainly is. These true stories of life on the hospital ward were scribbled in his diaries after endless days, sleepless nights and missed weekends.

Whether you have watched the TV adaptation or not, this essential story is best told through Adam Kay's original words.

Next, enjoy the best films based on books.