How to become a generalist in a world of specialists

If you want to be successful in any field, from music to sport or business, don't specialize – instead, develop a wide range of skills, says author David Epstein.

For years we've been taught that in order to succeed in any field – sport, music, business and beyond – the key is to specialize early and get hours of practice under our belts. But according to David Epstein, author of the New York Times bestseller The Sports Gene, in fact, the opposite is true. In his new landmark book, Range, David demonstrates through studies of international elite athletes, musicians, artists, inventors and scientists, that gaining a breadth of experience and skillsets is the way to succeed. Here, he reveals the research behind his theory.

Discover our edit of the best books about success.

You know the popular concepts. The 10,000-hours rule means you had better get started in focused, ‘deliberate practice’ in your speciality right away. The ‘grit scale’ deducts points for changing your interests. Amy Chua, on the very first page of her blockbuster, Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, advertised the secrets to raising ‘stereotypically successful’ children, including that her young daughters must play either piano or violin, for which she supervised up to five hours of practice a day. It all amounts to a tidy prescription for success: pick and stick, as early as possible.

But what does the research actually say? When scientists study the development of future elite performers in sports and in music—the domains most associated with early specialization—they tend to find what they call a ‘sampling period’. That is, future top performers do not pick and stick. They try a variety of sports, instruments, or musical genres in an unstructured or lightly structured environment, gain a breadth of general skills that scaffold later learning, gain insight into their own abilities and interests, and delay specializing until later than their peers who plateau at lower levels.

Find that hard to believe for a sport like football? Right after Germany won the 2014 World Cup, a study of German football players concluded that, compared to lesser players, members of the national team didn’t participate in more organized football than amateur-league players until age twenty-two or later. They spent more of their childhood and adolescence playing nonorganized football while also dabbling in other sports. Another football study published two years later matched players for skill at age eleven and tracked them for two years. Those who participated in more sports and more nonorganized football ‘but not more organized [football] practice/training’, improved more by age thirteen.

France, the most recent champions, began overhauling its development system decades ago to emphasize variety of physical challenges, athlete-led play (youth coaches aren’t allowed to talk during games outside of designated periods), and to deemphasize early selection. By 13, a French football player in the national development system might have played half as many games as an American prospect. (And we see how that has worked out.) As prominent sports scientist Ross Tucker summed up research in the field: ‘We know that early sampling is key, as is diversity.’

So what about music? The excerpt of Chua’s book that ran in the Wall Street Journal was the paper’s most commented-upon article ever. Few people remember the part later in the book, though, when Chua’s daughter, who was assigned violin, says: “You picked it, not me”, and quits most of her violin activities. Perhaps not a surprise, given that, in a study of twelve hundred young musicians, those who quit reported ‘a mismatch between the instruments [they] wanted to learn to play and the instruments they actually played’. The earlier that specialization occurs, the less likely a performer is to optimize their ‘match quality’, the term economists use to describe the degree of fit between an individual’s abilities, interests, and the work that they do. It happens to be extremely important for motivation and performance.

More important than sports and music, though, are the ways that early specialization narratives have leaked into the wider world. The bestseller Talent is Overrated, for example, used early specialization stories—a particularly dramatic one of young chess prodigies—to argue that a narrowly focused head start in deliberate practice is the key to success in ‘virtually any activity that matters to you’. In chess, a head start is indeed important. So important, in fact, that if rigorous study hasn’t begun by age twelve, the chances of reaching international master status (a level down from grandmaster) drops from one in four to one in fifty-five. But that is because the chess master’s advantage is based on knowledge of repetitive patterns. Chess is what the psychologist Robin Hogarth called a ‘kind learning environment’. All pertinent information is clearly available, patterns repeat, and feedback is typically rapid and entirely accurate. But most professions are not like chess. Much of the wider world of work involves what Hogarth called ‘wicked learning environments’, in which challenges can shift, rules may or may not be clear, and feedback is often delayed, inaccurate or both. In wicked learning environments, breadth is frequently a source of power.

In a study of comic book creators, for example, research found that neither years of experience nor the number of previous comics created predicted a creator’s performance, but the number of different genres a creator had worked across did. Studies on technological innovation have unearthed a similar theme: the most successful inventors are those who have spread their work across a large number of different technological classes—as classified by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office—rather than drilling more deeply into one. In scientific research, papers that cross domains to make ‘atypical knowledge combinations’ are far more likely than other papers to become smash hits in the library of human knowledge.

And yet, we remain obsessed with early specialization and precocity. At a recent Motley Fool investors’ event, the audience was polled on what they guessed was the average age of a founder of a blockbuster tech startup when the company was first launched. The runaway audience favourite was twenty-five. When Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg said, at twenty-two, that “young people are just smarter”, it resonated. And yet, researchers at Northwestern University, M.I.T. and the U.S. Census Bureau have shown that the answer is actually forty-five.

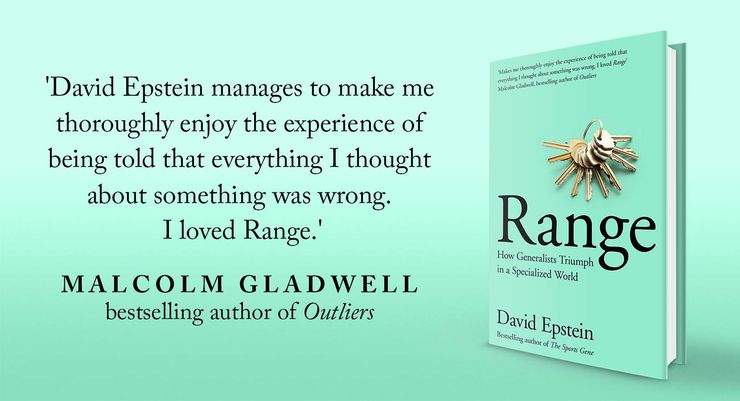

Even figures who are viewed as the titans of specialization have publicly nuanced their views. Just last month, Angela Duckworth, author of Grit, wrote a post titled ‘Summer Is For Sampling’, in which she advocates for a sampling period for young people, and mentions that it took her a decade to commit to a professional course. ‘Before specialization comes sampling’, Duckworth wrote, ‘the exploration of possibilities that, really, you cannot know anything about until you try them’. In March, Malcolm Gladwell, who popularized the 10,000-hours rule, said (in a public conversation with me) that in retrospect he feels that, “I conflated two separate things: a large amount of practice being necessary, which I think is true. But in the back of my mind, I thought that meant specialization, which I now realize is false.”

If Gladwell was willing to update his view, perhaps it is time for all of us to follow suit.

Watch David's TEDx Talk on how falling behind can get you ahead:

Range

In Range, David Epstein challenges the entrenched view that early specialization and hours of deliberate practice are essential if you want to succeed. He shows how sampling widely, experimenting relentlessly and juggling many interests – developing range – is the key to success, and how to achieve it.