Feminist history you might not have been taught at school

Meet four incredible women who may not have come up in history lessons – but definitely should have.

In Feminist History for Every Day of the Year, bestselling author and feminist champion Kate Mosse introduces inspiring figures from women's and girls' history, sweeping across the world and through the ages. Some you might already have heard of, and can now learn more about, but others will possibly be new to you. In these edited extracts from the book, we meet the woman who first identified global warming (in 1856!), the founder of the oldest continuing education institution in the world, a brilliant engineer, and a campaigner who fought for a woman's right to keep and control her own property.

Dorothée Pullinger

‘She was denied membership on the grounds that in their rules a ‘person’ meant a ‘man’, but she was not put off.’

Meet champion racing driver Dorothée Pullinger, a brilliant engineer and car designer. She was denied membership of the Institution of Automobile Engineers on the grounds that in their rules a ‘person’ meant a ‘man’, but she was not put off. In 1919, she cofounded the Women’s Engineering Society and helped set up an engineering college for women. In 1924, at the age of thirty, driving a Galloway she had helped design, she won the Scottish Six Day car trial. It is one of the most popular and respected road races, which tests not only speed but reliability, too.

During the Second World War, Pullinger set up the women’s industrial war work programme and ran thirteen factories. She was the only woman on a post-war government committee formed to recruit women into factories.

After the war was over, the Institution of Automobile Engineers finally accepted her as their first female member. In 2012, twenty-six years after her death, she was the first woman to be inducted into the Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame.

Caroline Norton

‘Most people would have admitted defeat, but Norton refused to accept the injustice.’

When British women married in the nineteenth century they had no right to keep their own property or inheritance, no right to their own earnings and no right to have access to their children. Married women were, essentially, the property of their husband and had no independent existence in the eyes of the law.

Born on 22 March 1808 in London, Norton was a novelist, a wealthy socialite, a playwright, pamphleteer and poet. Despite her advantages, she was married to an emotionally abusive and jealous man. He ill-treated her to such an extent that she left him in 1836. In retaliation, he accused her of adultery – known as ‘criminal conversation’ – and took her to court. The case was thrown out, but Norton was left nearly bankrupt and separated from her three sons.

Most women would have admitted defeat – in Victorian England, the law was administered by men, for the benefit of men. That’s just how it was. But Norton refused to accept the injustice and began a campaign to change the law. Thanks to her, and others, three key pieces of legislation affecting women’s lives were passed, including the Married Women’s Property Act in 1870. This ruled that women should be able to keep and control their own property in certain circumstances, and allowed a woman’s earnings to be considered her own property, not her husband’s.

Eunice Newton Foote

‘The male speaker failed to recognize the implications of her discovery so he didn’t get across how important it was.’

Would it surprise you to learn that the phenomenon known as global warming was first identified as far back as the 1850s?

In 1856, the American suffragist, scientist and inventor Eunice Newton Foote discovered what we now call ‘greenhouse gases’. Having done experiment after experiment to double and triple check her findings, she tried to persuade the American scientific community to let her speak. They would not listen and, in August of that year, Foote was forced to sit in the audience at an AAAS (American Association for the Advancement of Science) meeting while a male scientist presented her research.

He did a terrible job! He failed to recognize the implications of her discovery – that’s to say that increased carbon dioxide in the atmosphere would cause global warming – so he didn’t get across how important Foote’s discovery was.

Frustrated, Foote tried again. But because she couldn’t explain exactly how the greenhouse effect worked, when another scientist figured out that piece of the puzzle three years later, the discovery was credited to him rather than her. It wasn’t until 2011, 123 years after her death, that her critical role was acknowledged.

Fatima bint Muhammad al-Fihriya

‘Inheriting a large fortune, al-Fihriya used her wealth to improve society.’

On 3 September 1965, the al-Qarawiyyin Mosque in Morocco was named a university. It had been established as a mosque and place of learning by Fatima al-Fihriya in 857–859 ce.

What little we know of Fatima’s life comes from the work of a medieval writer and scholar writing hundreds of years after her death, so it is hard to substantiate. But it’s thought she was born into a privileged family in Tunisia who moved to Morocco when she was a child. Inheriting a large fortune on the death of her father and then her husband, al-Fihriya used her wealth to improve society. Known as the ‘mother of boys’, or sometimes the ‘mother of children’, because of her focus on learning, the al-Qarawiyyin Mosque is the oldest continuing education institution in the world. And founded by a woman . . .

Discover more stories of incredible women throughout history

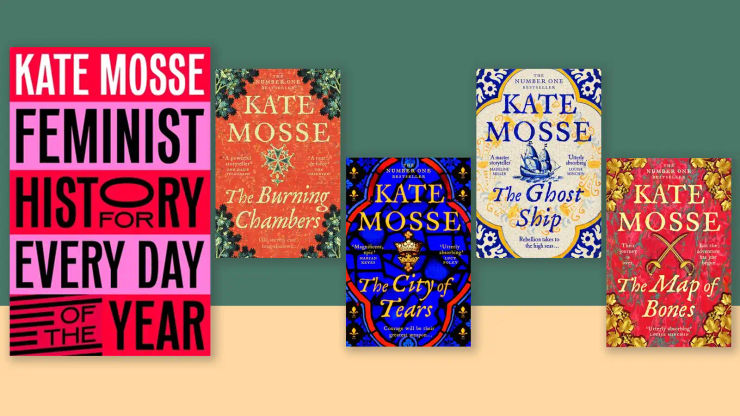

Feminist History for Every Day of the Year

by Kate Mosse

This beautifully illustrated book celebrates women and girls from throughout history, providing 366 incredible stories to inspire readers of all ages. Perfect for curious and lifelong learners, this book is a brilliant collection of key cultural moments and forgotten stories, from ancient times to the modern day.