Elton John on life, fate and embracing your bad side

Global superstar Elton John tells us about the importance of owning our ‘bad sides' and his experiences of committing his life to paper.

‘I can’t stand books or movies about rock stars that give you some whitewashed version of reality, that are intent on telling you what a wonderful, perfect person they are. It’s boring, because it’s a lie: no one is perfect, and certainly no rock star is perfect.’

Elton John has lived a life few could fathom. A veritable diamante-clad rollercoaster of soaring highs, self-discovery and critical acclaim that at times, plunged to devastating lows. His, it seems, is a life lived at high velocity, and while all-that-glitters may have dominated his story thus far, his autobiography Me is Elton at his warmest, humblest and most-open.

Here, in his own words, Elton tells us about some of the relationships that have shaped his story, his experience of committing his life to paper in his first and only official autobiography, and the power and freedom to be found in telling the truth: the good, the bad, and the not-so-dazzling.

‘You start reminiscing about the good old days and you view it all through rose-tinted spectacles: in my case, I think that’s forgivable, because I probably was wearing rose-tinted spectacles at the time’

— Elton John

Let me tell you a story.

I should probably begin telling you about my autobiography by telling you that I never wanted to write an autobiography. Or at least, for years, I thought I didn’t. I’ve never been terribly interested in looking back at my career. It happened, I’m incredibly grateful, but I’m more concerned about what I’m doing next rather than what I did forty or fifty years ago. I think nostalgia can be a bit of a trap if you’re an artist. You start reminiscing about the good old days and you view it all through rose-tinted spectacles: in my case, I think that’s forgivable, because I probably was wearing rose-tinted spectacles at the time, with flashing lights and ostrich feathers attached. But if you do that, you can end up convincing yourself that everything was better in the past than it is now. If you start thinking that as an artist, you might as well give up writing music for a living and retire.

And I’ve never really thought of myself as a writer, at least as far as words are concerned. I tried writing lyrics at the very start of my career, when I was the organist in a band called Bluesology. I was the only member of the band who wrote songs at all, so it was up to me. The memory of the lyrics I wrote for Bluesology can still wake me up at night in a cold sweat. But I didn’t need to write lyrics. I had Bernie Taupin to do that.

‘“Neither of us can write if the other is in the room. But from the moment I opened the envelope with Bernie’s lyrics in it, on the train home from central London to Pinner, I felt an instant connection . . . I could hear the music I was going to set them to.” ’

— Elton John

I always talk about how completely different we are, how we were thrown together more or less by accident and how I’m not sure why our song-writing partnership works. That’s all true. We were thrown together more or less by accident: I had failed an audition for Liberty Records in 1967, and a guy from the label gave me an envelope with Bernie’s lyrics in it as an afterthought, like a consolation prize. I’m not sure he had even opened the envelope and read the lyrics himself before he did it. I think he just felt sorry for me and didn’t want me to go away empty-handed. And we are completely different people. He comes from the wilds of Lincolnshire, I come from the suburbs of London. He lives in Santa Barbara and he’s literally won competitions for roping cattle. I live just down the road from Windsor Castle, I collect antique porcelain and the only way you’d get me on the back of a horse is at gunpoint. Neither of us can write if the other is in the room. But from the moment I opened the envelope with Bernie’s lyrics in it, on the train home from central London to Pinner, I felt an instant connection. That had never happened with anyone else, and it’s never changed.

And the connection works both ways. There are times when Bernie’s written lyrics from my point of view, and he’s expressed how I felt better than I could. Anyone who was surprised when I came out in 1976 – who’d apparently seen me perform, without for a moment considering that the man being carried onstage by an oiled-up bodybuilder while wearing half the world’s supply of diamanté, sequins and marabou feathers might be anything other than straight: hello? – clearly hadn’t been listening to the lyrics Bernie wrote for “All the Nasties” in 1971. It’s a song about me, wondering what would happen if I came out publicly: “Would they criticize behind my back? Maybe I should let them.” In 1980, he wrote a song called “White Lady White Powder,” a portrait of a hopeless cocaine addict – “I’m a catatonic son of a bitch who’s had a touch too much white powder” – which I had the brass balls to sing as if it was about someone other than me. And if you wanted to know how lost I was in the years immediately before I went into rehab in 1990, you only have to listen to “I Fall Apart,” from Leather Jackets. That is, if you can stand to listen to Leather Jackets, in which case you’re made of stronger stuff than me: it isn’t so much an album as an experiment to see how much cocaine a man can take in a recording studio without being certified insane.

But then things changed. First, it was my attitude to looking back at my past. Actually, it was Bernie who really started that, around the turn of the millennium. He wasn’t happy at all about the direction our albums had taken in the ’90s. In fact, he flew all the way from America to my house in Nice for the express purpose of telling me that the last album we had made, The Big Picture, was the biggest pile of boring, middle-of-the-road crap he’d ever heard in his life. He thought we should go back to making records the way we had in the early ’70s or, rather, think about the way we had made records in the early ’70s, take ideas and develop them in a different way. I liked that: I called it “going backwards to go forwards.” It was the approach we used on Songs from the West Coast in 2001, and a lot of albums we’ve made since then.

‘“I wanted something [my sons] could read and something they could see and think, well, that was our dad, that was what he did, that was what he was really like. I don’t mind people knowing about my bad side – and at my worst, my bad side was pretty dreadful.” ’

— Elton John

But for all I’d started thinking about my past in a different way, I didn’t think about actually writing a book until David and I had kids. I was sixty-three when our first son, Zachary, was born, sixty-five when Elijah came along, and it made me think about them in forty years’ time, being able to access my version of my life. It was the same impulse that made me go ahead with Rocketman. I became less conscious about keeping my version of events to myself, because I liked the idea of them having an autobiography and a film, where I was honest, no holds barred, no punches pulled. I didn’t want a book or a film that gave some sugar-coated version of events. I wanted something that was truthful, the way Tantrums and Tiaras, the documentary David made about me when we first met, was truthful. I wanted something Zachary and Elijah could read and something they could see and think, well, that was our dad, that was what he did, that was what he was really like. I don’t mind people knowing about my bad side – and at my worst, my bad side was pretty dreadful.

When I started work on Me, I found, unexpectedly, that I really enjoyed it. I realized how lucky I was to have had a career that didn’t just deal with music, but that touched on film and art and fashion as well. I became fascinated with the way that so much of my life depended on fate, odd little moments that seemed completely insignificant at the time, but that changed everything. What if I’d passed the audition at Liberty Records in 1967, so they hadn’t felt obliged to hand me the envelope with Bernie’s lyrics in it? What if I had felt so dejected that I hadn’t bothered to open the envelope? What if I’d won the argument I started about the pointlessness of going to play at the Troubadour in 1970? I didn’t see any reason to go. I was getting a bit of attention in Britain at the time. Not much, just the odd review and occasional play on the radio, but there was more momentum here than there was in America, where literally no one knew who I was – I had no idea the gigs in LA would be the event that kick-started my career. What if I hadn’t picked up a magazine that had a feature about Ryan White in a doctor’s surgery in 1986? It was meeting Ryan, a teenager who’d contracted AIDS from a blood transfusion, that ultimately caused me to go to rehab and turn my life around. That kind of thing seems to have happened over and over again to me.

‘One minute, I was a jobbing musician in London, doing session work, playing for anyone who’d have me . . . I came back from the States a month later with American critics literally calling me the “Saviour of Rock ’n’ Roll.’

— Elton John

But most of all, I found it was funny. Looking back at my career made me realize how ridiculous it was. It took off in a ridiculous way. One minute, I was a jobbing musician in London, doing session work, playing for anyone who’d have me, trying to sell the songs me and Bernie had written to a largely disinterested world. I came back from the States a month later with American critics literally calling me the “Saviour of Rock ’n’ Roll.”

It was all so overwhelming that for the first few years, I kept a diary the whole time, and it’s inadvertently hilarious. I wrote everything down in this matter-of-fact way, which ends up making it seem even more preposterous: “Woke up, watched Grandstand. Wrote ‘Candle in the Wind.’ Went to London, bought Rolls-Royce. Ringo Starr came for dinner.”

‘I don’t think any human being is psychologically built to cope with all that stuff happening to them that quickly, let alone me. In a way, it’s a miracle I didn’t go off the rails before I did.’

— Elton John

I suppose I was trying to normalize what was happening to me, but the fact was, what was happening to me wasn’t normal. I’m not complaining at all, but there was no way you could prepare yourself for it. I don’t think any human being is psychologically built to cope with all that stuff happening to them that quickly, let alone me. In a way, it’s a miracle I didn’t go off the rails before I did. Of course, when I did go off the rails, I went off the rails in the most ridiculous manner imaginable too: my excesses were excessive even by the standards of the most excessive era in rock. You know, it took a fairly Herculean effort to get yourself noticed for taking too much cocaine in the music industry of ’70s LA, but I was definitely prepared to put the hours in.

I’m not proud of how I behaved, but revisiting it wasn’t painful, at least for the most part. There are moments in the book that I don’t come out of very well, where I seem completely disgusting and awful, but I was completely disgusting and awful, and there’s no reason to pretend otherwise. It’s like Tantrums and Tiaras. People said I was crazy to allow that film to be released, but it’s one of the few films about me I actually like, because it’s real. I can’t stand books or movies about rock stars that give you some whitewashed version of reality, that are intent on telling you what a wonderful, perfect person they are. It’s boring, because it’s a lie: no one is perfect, and certainly no rock star is perfect. They can be horrible sometimes. They can be fabulous and charming and they can be outrageous and stupid. That’s what I wanted to show in Tantrums and Tiaras, that’s what I wanted to show in Rocketman and that’s definitely what I wanted to show in Me.

There's one week to go until the paperback of my book is out, and for those that don't know, there's a brand new chapter which captures the highs and lows of the last year. Here's a sneak peek - my reaction to seeing #Rocketman for the first time... 🚀 #EltonJohnBook pic.twitter.com/jfuGlHpJFk

— Elton John (@eltonofficial) October 7, 2020

You could see Me as a kind of counterpoint to Rocketman. The film is a fantasy based on fact: I definitely did try and kill myself in front of my family in the middle of a party by taking an overdose and throwing myself into a swimming pool, but I actually didn’t sing “Rocket Man” while I was doing it. The phrase I used was that it wasn’t all true, but it was the truth. But the book is all true, the ridiculous reality of my life in all its funny, mad, horrible, dark, and brilliant, glory. I’m just incredibly grateful that I lived to tell the tale. Sometimes it reads like a particularly lurid work of fiction, sometimes I struggle to believe it myself, but it all happened. And it happened to me.

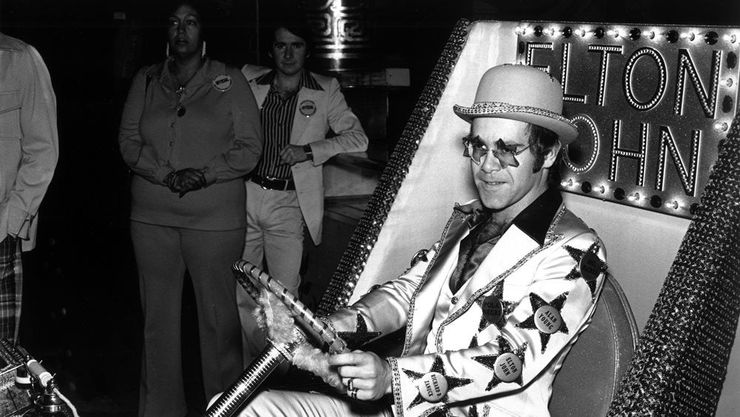

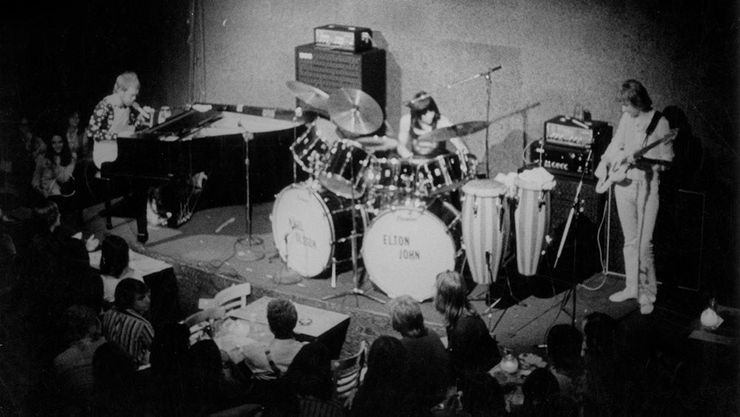

Header image: Elton performing in 1974. © Sam Emerson (courtesy of Rocket Entertainment)

Me

by Elton John

Elton John reveals the truth about his extraordinary life, from his first gig in America wearing yellow dungares and a star-spangled T-shirt to disco dancing with the Queen, and from drug addiction to finding love with David Furnish. Me is a story that will stay with you, from a living legend.

If you like autobiographies, check out our collection of the best auto biographies & memoirs.