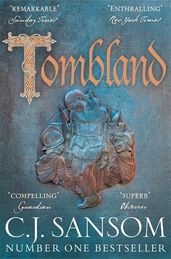

The true events that inspired C. J. Sansom’s Tombland

C. J. Sansom on the fascinating true history that inspired his bestselling novel.

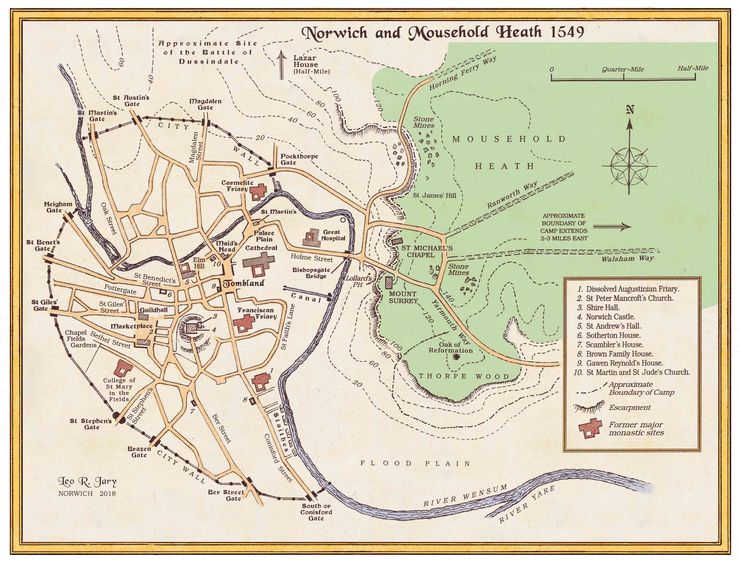

Tombland is the seventh novel in C. J. Sansom’s bestselling Shardlake series. Set in the summer of 1549, lawyer Matthew Shardlake investigates the death of a distant relative of Henry VIII’s daughter Lady Elizabeth, amidst the chaos of Kett’s Rebellion. Full of mystery, danger and divided loyalties, this is another gripping read from C. J. Sansom. Here, we look at the real-life history surrounding the story, and visit some of the historic Norwich landmarks which feature in the book.

In this extract from the historical essay 'Reimagining Kett’s Rebellion' which accompanies Tombland, C. J. Sansom discusses some of the true historical events which inspired the seventh Shardlake novel.

In April 1548, the year before Kett’s Rebellion, an orphaned minor gentlewoman of around fourteen, Agnes Randolf, was riding over Mousehold Heath with her married older sister and a young servant. They were accosted by John Atkinson, servant to Sir Richard Southwell, one of the most prominent gentlemen in Norfolk, and a companion. Atkinson attempted to abduct Agnes and when she tried to escape tied her on to his companion’s horse, saying, ‘Sit, whore, sit.’ She was taken to Sir Richard Southwell’s house and, later that week, forced to go through a marriage ceremony with Atkinson. Then he took her to London.

Agnes’s brother-in-law, Thomas Hunne, seems to have been a man of remarkable determination. He went to London and himself presented a supplication to Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset and Lord Protector of England during the minority of Edward VI, as the Protector entered the council chamber at Westminster. Such direct access to the ruler would have been inconceivable under Edward’s father Henry VIII, but it was part of Somerset’s style to show himself accessible to those seeking justice. Two days later Southwell was examined before the Council, and Atkinson committed to prison.

Then problems began. Hunne made suit to the Council for Agnes to be restored to him, but was told by William Cecil, Somerset’s senior secretary, that he should obtain legal counsel. No fewer than seventeen East Anglian lawyers, however, refused to represent him until Cecil ordered one to do so. Such, apparently, was the fear that Southwell inspired. Cecil tried to persuade Agnes to let the marriage stand but, as determined as her brother-in-law, she refused. Cecil then said she must return the wedding ring, which she immediately did.

Although under suspicion of abducting a minor, Atkinson was released. For the next four years, however, he tried to force Agnes’s return through the courts, on the grounds that they had been lawfully married – even after Agnes had, later, married someone else. Norfolk gentlemen could be extraordinarily obsessive.

This story features three people who appear in Tombland – Southwell, Atkinson and Cecil. It demonstrates the power wielded, in Norfolk and London, by Southwell, the brutality of which he and his entourage were capable (he had been found guilty of murdering another gentleman during a quarrel in London in the 1520s, but obtained a pardon from Henry VIII), and both Protector Somerset’s accessibility and its limits. Were it not for the great courage of Agnes and her family, the marriage would have stood. It is worth noting that Agnes’s family had gentleman status; their clothes, bearing and accents would have aided their way into the Protector’s court. One wonders how a peasant family might have fared.

It is however the ‘non-gentle’ classes who feature most prominently in Tombland, those who made the huge peasant uprisings that swept England in 1549. Roughly south of a line between the Severn and the Wash, though there were also risings north of there, common people set up camps outside towns and sent petitions to the Protector. It was the largest popular uprising between the 1381 Peasants’ Revolt and the Civil Wars a century later. There were substantial pitched battles between rebels and government forces in the West Country, Oxfordshire and Norfolk. The Venetian ambassador estimated that 11,000 died in the rebellions; as a proportion of the population, today’s equivalent is almost 150,000.(2) If anything this is probably an underestimate, since casualties among government forces were played down.

Yet most popular histories of Tudor England say little about the rebellions. There are several reasons: their unusual structure – forming ‘camps’ instead of marching as a single force on London; the misconception among historians, until fairly recently, that the only serious revolts were in the West Country, where they were concerned mainly with religious changes, and in Norfolk where they focused on social issues. However recent studies by Dairmaid MacCulloch, Andy Wood, Ethan Shagan and most especially Amanda Jones have shown the number and the connectedness of the risings across southern England.

Perhaps also, in these days of the ‘royalization’ of popular Tudor history (I do not exempt myself from guilt here) – focusing on the larger-than-life personalities of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I – a rebellion that took place during the short reign of Henry’s son, Edward VI, is less likely to gain attention. But the rebellions of 1549 caught my imagination a long time ago, as a colossal event that has been much underplayed.

In this episode of Book Break, Emma visits the historical landmarks of Norwich, including some which feature in C. J. Sansom’s novel, and finds out more about Kett’s Rebellion.

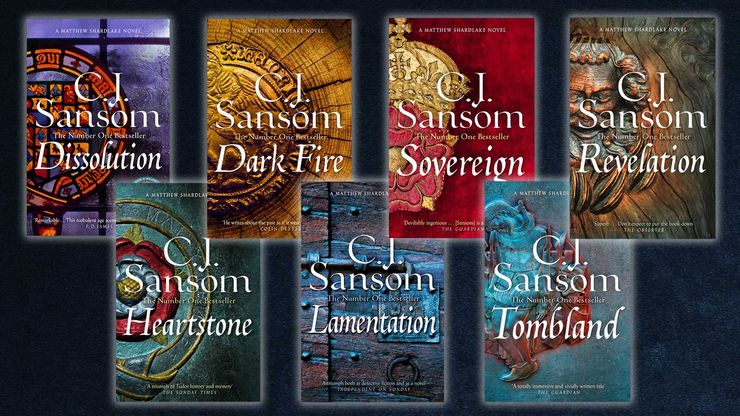

Discover the first six novels in the bestselling Shardlake series.

Tombland

Since Henry VIII’s death, Matthew Shardlake has been working as a lawyer in the service of Henry’s younger daughter, the Lady Elizabeth. The gruesome murder of Edith Boleyn – a distant Norfolk relation of Elizabeth’s mother – which could have political implications for Elizabeth, brings Shardlake and his assistant Nicholas Overton to the summer assizes at Norwich. There they are reunited with Shardlake’s former assistant Jack Barak. The three find layers of mystery and danger surrounding Edith’s death, as a second murder is committed and East Anglia explodes, peasant rebellion breaking out across the country.