TV shows you didn't know were based on books

You loved them on the small screen, but did you know they started on the page?

Here's a selection of our favourite book-to-TV adaptations, including some you may not have realised have literary source material.

Dark Matter

Now an Apple TV+ series starring Jennifer Connelly and Joel Edgerton, Dark Matter is a mind-bending thriller about the choices we make, and the paths we don't take.

Dark Matter

by Blake Crouch

Knocked unconscious by an anonymous attacker, Jason Dessen comes round in a new life. He has a different wife. No son. And he's not a college professor, but a renowned genius who has just achieved the impossible. Is it this world or the other that's the dream? And if his memories of his old life are real, how can he get back to it? A relentlessly surprising thriller about choices, paths not taken, and how far we'll go to claim the lives we dream of.

Shardlake

C. J. Samson's historical mystery series has been adapted for the small screen in a four-part series on Disney+.

The Doll Factory

Now a major news series on Paramount+, the dark Victoriana of The Doll Factory comes from Elizabeth Macneal's debut novel of the same name.

The Doll Factory

by Elizabeth Macneal

London. 1850. On a crowded street, the dollmaker Iris Whittle meets the artist Louis Frost. Louis is a painter who is desperate for Iris to be his model. Iris agrees, on the condition that he teaches her to paint. Dreaming of freedom, Iris throws herself into a new life of art and love, unaware that she has caught the eye of a second man. Silas Reed is a curiosity collector, enchanted by the strange and beautiful. After seeing Iris at the site of the Great Exhibition he finds he cannot forget her. As Iris's world expands, Silas's obsession grows. And it is only a matter of time before they meet again . . .

Not Dead Yet

Available on Disney+ in the UK, Not Dead Yet is based on Alexandra Potter's hugely successful Confessions of a Forty-something F**k Up. The American series changes up the name, switches Nell's nationality and adds a spectral twist, but the heart, humour and central story of this funny, moving read remains at the heart of its TV adaptation.

Confessions of a Forty-something F**k Up

by Alexandra Potter

Meet Nell. Her life is a mess. Having left a great job in New York to start a new life in California with the man she loves, she's now back in London under a literal and metaphorical cloud. Unemployed, living in a stranger's spare room and having to compete with children, careers and a wealthy usurper called Annabel for the attention of her friends, she starts up a secret podcast as an outlet for her entertainingly expressed but deeply heartfelt frustration. Through this, alongside an unexpected friendship with octogenarian widow Cricket, things finally start to look up.

This is Going to Hurt

OK, the name's a big clue here. But the shift from memoir to television drama is significant enough that those yet to read Adam Kay's bestseller may not realise that the show is based on diary entries, with most of the characters created for the series rather than lifted from the book.

This is Going to Hurt

by Adam Kay

This is Going To Hurt is a no-holds-barred account of life as a junior doctor, which began life as a comedy show inspired by the junior doctors’ strike. Written in secret between grueling hospital shifts, the book is by turns shocking, sad and laugh-out-loud funny, while telling you everything you ever need to know – and more – about life on a hospital ward. Highlighting the long hours, poor pay and staffing problems caused by underfunding, this is a must-read for anyone who values the NHS.

Les Misérables

You may well have heard of the musical, but you may be less familiar with the nineteenth-century French masterpiece that both it and the TV series are based on.

Les Misérables

by Victor Hugo

Escaped convict Jean Valjean attempts to rebuild his life as an honest man, and takes in an abandoned orphan, Cosette, to raise as his own. But police officer Javert's ruthless pursuit of Valjean means he can never escape his past. Meanwhile, as Cosette grows up, young idealist Marius catches a glimpse of her and falls desperately in love, and the fates of all the characters become intertwined with the violent turmoil of the 1832 June Rebellion.

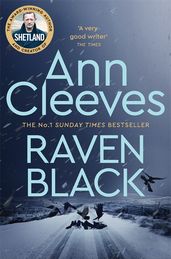

Shetland

Ann Cleeves is no stranger to TV adaptations, with three of her atmospheric detective series now on television. Raven Black is the first book in her bestselling Shetland series, which you can watch on the BBC, and you'll find Vera and The Long Call, based on her Two Rivers series, on ITV1.

Raven Black

On New Year’s Day, Shetland lies buried beneath a deep layer of snow. Trudging home, Fran Hunter's eye is drawn to a vivid splash of colour on the white ground, ravens circling above. It is the strangled body of her teenage neighbour. The body is found close to the home of a lonely outcast and local suspicion falls firmly on him. But when Inspector Jimmy Perez insists on broadening the search for suspects, a veil of distrust and fear is thrown over the entire community. As the case develops, Perez finds himself peering deeper into the past of the Shetland Islands than anyone wants to go.

Lovecraft Country

Produced for TV by Jordan Peele's Monkeypaw Productions, Lovecraft Country is based on the horror novel by Matt Ruff.

Lovecraft Country

by Matt Ruff

Lovecraft Country combines the mundane terrors of white America with malevolent spirits and a secret ritualistic cabal to entertaining and thought-provoking effect. In 1950s Chicago, Army veteran Atticus Turner sets out to find his missing father, alongside his Uncle George and childhood friend Letitia. They're aiming for New England, and the home of Samuel Braithwaite, heir to the estate that owned one of Atticus's ancestors, and what they find there is even more sinister than they imagined.

Love, Death + Robots

The first episode of Netflix anthology series Love, Death + Robots is based on Peter F. Hamilton's short science fiction story Sonnie's Edge.

A Second Chance at Eden

by Peter F. Hamilton

A short story collection from science fiction master Peter F. Hamilton. Existing fans may recognise the universe from the Night's Dawn trilogy, but you don't need to be familiar with Hamilton's work to enjoy this compelling mix of human dilemmas, imagined technologies and extraordinary new cultures. Sonnie's Edge sees the titular protagonist fighting to stay ahead in the underground world of constructed monster fighting.

Little Fires Everywhere

Big-hitters Reese Witherspoon and Kerry Washington's miniseries is based on Celeste Ng's novel of the same name.

Little Fires Everywhere

by Celeste Ng

In Shaker Heights, residents tend to play by the rules. Especially the Richardsons. Enter Mia Warren – an enigmatic artist and single mother – who arrives in this idyllic bubble with her teenage daughter Pearl, and rents a house from the family. When old family friends attempt to adopt a Chinese-American baby, a custody battle erupts that dramatically divides the town and puts Mia and Elena Richardson on opposing sides. Suspicious of Mia and her motives, Elena is determined to uncover the secrets in Mia's past. But her obsession will come at an unexpected and devastating cost . . .

You Don't Know Me

This gripping courtroom drama is based on Imran Mahmood's dazzling debut novel.

You Don't Know Me

by Imran Mahmood

An unnamed defendant stands accused of murder. The evidence is overwhelming. But just before the Closing Speeches, the young man sacks his lawyer, and gives his own defence speech. It is about the woman he loves, who got into terrible trouble. It's about how he risked everything to save her. His barrister told him not to tell the full story. Now, as he talks us through the eight pieces of evidence against him, his life is in our hands. We, the reader – member of the jury – must keep an open mind. He swears he's innocent. But in the end, all that matters is: do you believe him?