Kate Mosse presents the women in whose footsteps we walk

On January 27th, Kate Mosse launched #WomanInHistory, a global campaign to nominate incredible women from any period of history, anywhere in the world, so that collectively we may celebrate and honour their legacies. Here, Kate presents just some of the world-changing women nominated.

Welcome to #WomanInHistory, the global campaign to honour and celebrate the incredible women of the past in whose footsteps we walk.

As an historical novelist, I spend a fair amount of time in archives and libraries and museums, examining old documents, reading and re-reading history, peering at maps and paintings, analysing objects that might sum up a character’s time, their story - a psalter, a shoe, a child’s rattle, a sword, a last will and testament. At the heart of my fiction are underheard and unheard women’s voices, the heroic ordinary women – who are, of course, anything but ordinary – whose day-to-day lives are too often left out of the official histories. Over the years, I’ve become more and more aware of how easily and how quickly many women, even those who were lauded in their day, can disappear from the official record.

The idea with #WomanInHistory is simple: to acknowledge women from every race, every age, every country of origin or adoption, working in every field and to applaud their achievements. To put their names back into the history books.

Within the first few days of launching the campaign in January 2021, we had thousands of nominations from every corner of the globe - Syria, Scotland, New Zealand, Iran, Nigerian, Turkey, China, Pakistan, France, Iceland, England, Germany, Wales, Poland, Ireland, Japan, Korea, India, Slovakia, Greece, North America, Brazil, Wales, Vietnam, Argentina, Vietnam, Nigeria, you name it! Women from every period of history - the far distant past, the recent past and those who are making history today – and working in every discipline: scientists, inventors, sportswomen, spies, chemists, journalists, writers, medics, rebels, leaders, martyrs, painters, composers, campaigners, actors, women of courage and warrior queens, astronauts and engineers, sculptors and philanthropists, conservationists, astronomers, physicists, pirates, agents of change, poets, designers, women of faith and women of conviction, women who refused to accept limitation, women who stood up for what they believed, women who stood up for others. Quiet revolutionaries and those who burned bright. Some of the names are familiar, others should be far better known or more generally known outside their communities. Too many are women who had to live with their achievements being ignored, misrepresented or misattributed.

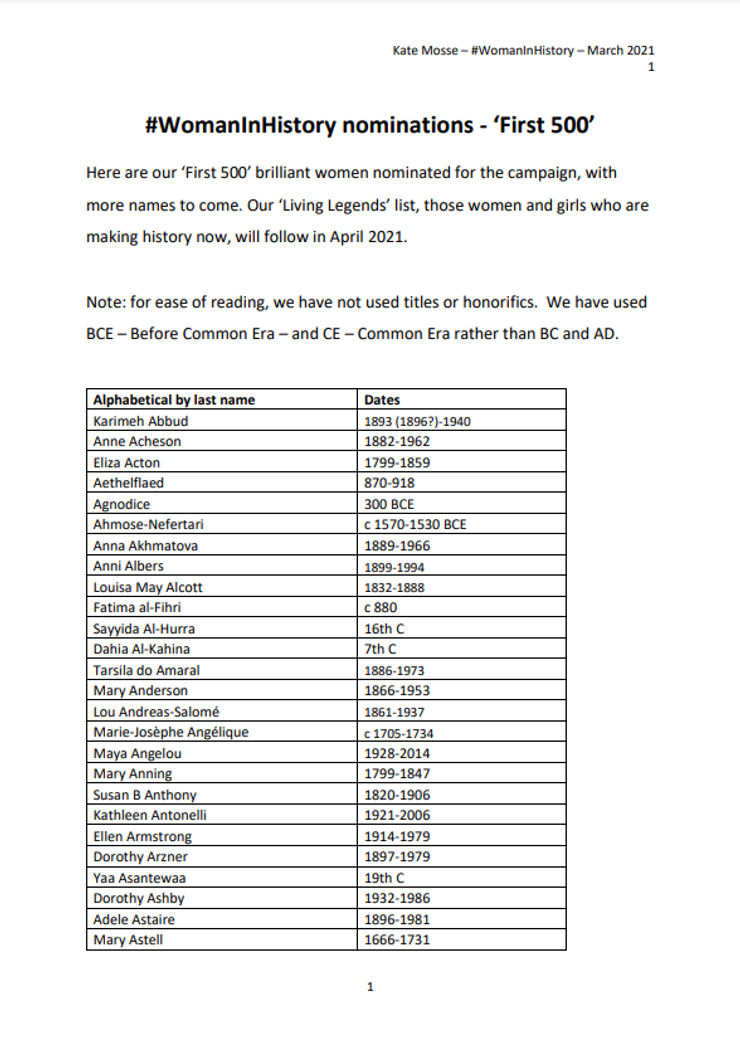

Our original intention in launching #WomanInHistory was to publish all the names of those nominated on 8th March 2021, International Women’s Day. But, thanks to the sheer volume of suggestions, we’ve decided to begin with celebrating our ‘First 500’ – available as a downloadable document – with further lists to be added, as the mighty job of putting together biographies, checking dates and names continues.

I am delighted to say we’ll be publishing a book. There will be stories that make you gasp, laugh, applaud, weep, despair, admire, sigh, punch the air. On the pages that follow, I’m sharing just a few of those stories to whet your appetites. A recommended reading list of further reading – memoir, research, biography, histories, collections about amazing women of the past - is available on www.bookshop.org/katemosse and we’ll be adding to that too as this project progresses. We’re also putting together a list of organisations and social media campaigns working in this same area, from @OnThisDayShe and @she_made_history to educational charities such as @the_female_lead and other trade organisations.

#WomanInHistory is about celebration. It’s about making a contribution in this area where many women and organisations all over the world are already promoting and advocating for women of the past. It’s about being inspired, about honouring all the women to whom the world owes so much, it’s about putting women back at the centre of history.

Kate Mosse

Founder of #WomanInHistory

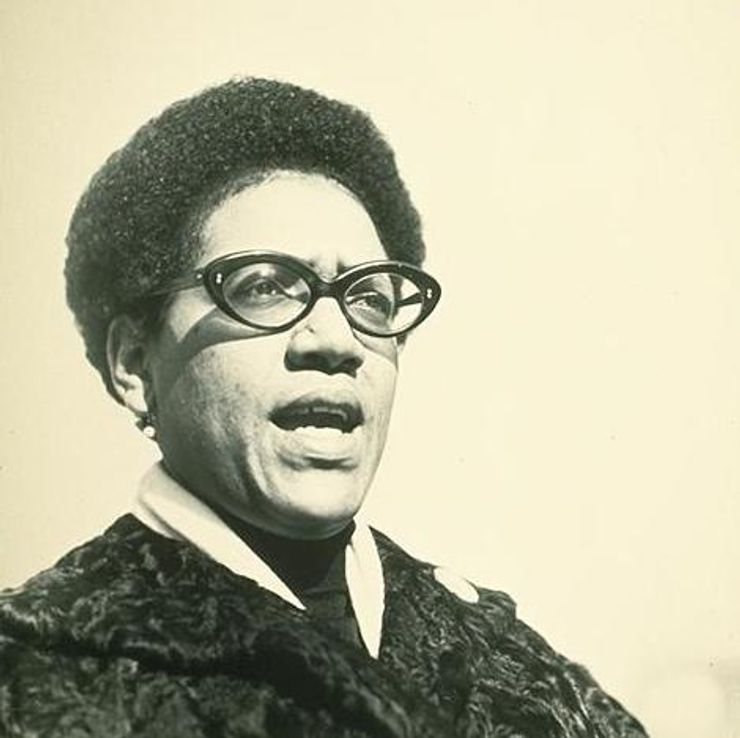

‘A Book of Myths’

The last words of ‘Diving into the Wreck’ - the title poem in the 1973 collection by Adrienne Rich, the great American feminist thinker, poet and essayist - are these: ‘a book of myths/in which/our names do not appear.’ At the heart of the poem – and, indeed, the whole beautiful and fierce collection about women’s liberation and the silencing of women’s voices - is a question. What is history? Who decides which stories are told and which are peripheral? Who judges what matters, whose views should be heard? Who is it who chooses the names to be written in the ‘book of myths’? When ‘Diving into the Wreck’ won the National Book Award for Poetry the following year, Rich shared it with her fellow nominees Audre Lorde and Alice Walker. The three poets had written the statement together and agreed that whoever won would accept the award on behalf of ‘all the women whose voices have gone and still go unheard ….’

From school textbooks and reference books in libraries, from the documents we seek out in archives and museums, it’s evident to see how easily women’s achievements vanish from the official record. It’s a cliché to say that history is written by the victors, though nonetheless true for all that. It’s also written with an agenda – to ‘prove’ just cause, to ‘prove’ superiority on the grounds of gender, age, race, disability, faith, tradition, to shore up power. But why are women’s contributions and experiences so often overlooked or misattributed? Is it accident, design, politics, neglect?

Is it because recorded history has, for the most part, been traditionally vested within institutions of learning where women were not allowed? Or is it a question of rewriting history to suit the customs of the time? Is it the willingness, or lack of it, of a family wanting to safeguard her legacy? All of these reasons, or none? This same spirit of rewriting the ‘book of myths’ – coupled with curiosity and admiration - is at the heart of #WomanInHistory.

Warrior Women & Queens of Antiquity

The issue of evidence and the challenges of gathering data from the far distant past, of course plays its part in how so many women disappear from history. All the same, the issue of who ‘makes’ history or get to decide what matters, what does not, is critical. Did you know, for example, that the woman credited with being the first female midwife and physician in 4th-century Athens, Agnodice, disguised herself as a man in order to be able to study medicine in a period when it was illegal for a woman to do so? Or how the only record of the warrior queen Cartimandua, who ruled the Brigantes, a Celtic tribe in the north of England, between 43 CE – 69 CE, comes from the writings of Tacitus? Or that Fatima al-Fahri, who died in 880 CE, was responsible for the al-Qarawiyyin Mosque and founding the world’s oldest university in Fez 859?

The historical record is more to be relied upon when it comes to rulers, queens, regents, empresses whose lives were lived in the public gaze. From the 3rd-century Zenobia (c 240 - 274 CE), Queen of the Palmyrene Empire in Syria, who ruled as regent for her son after her husband’s assassination, to Hatshepsut (1507 – 1458 BCE) in Egypt, widowed and usurped her son to become Egypt’s second and fearless female Pharaoh (the first was Sobekneferu). In her twenty-one-year rule, her public portrayal was as a man. Wu Zhao (624-705) – commonly known as Wu Zetian - of the Tang dynasty, is the only woman to have sat on the throne of China in her own right.

Many of these warrior queens of antiquity have been immortalised in works of literature, theatre, film, painting. One of the most frequently nominated rulers in #WomanInHistory was Eleanor of Aquitaine, Queen Consort of France and England in the 12th century, the Duchess of Aquitaine. The fifteenth and sixteenth centuries – the period I’m researching for The Burning Chambers series - was a period of several strong female leaders in Europe: Margaret Tudor (1489 – 1541), who was Queen consort of Scotland from 1503 until 1513 by marriage to James IV of Scotland, then regent for their son James; Elizabeth the First (1533 – 1603) in England and Catherine de’ Medici (1519 – 1589) and Jeanne d’Albret, Queen of Navarre (1528 – 1572) in France, both of whom appear in The City of Tears.

A queen nominated by novelist Sara Collins amongst many others, Queen Nanny of the Maroons was born in Ghana in 1686. Leader of a community of formerly enslaved people known as the Windward Maroons, Nanny is a legendary figure in Jamaica as, in India, is Lakshmibai, Rani of Jhansi (1828 – 1858), one of the leading figures of the Indian Rebellion of 1857. She died in action with her sword in her hand. In 1851, Seh-Dong-Hong-Beh, leader of the Dahomey Amazons, led an army of 6,000 female warriors against the Egba fortress.

The Pen is Mightier

Virginia Woolf famously wrote: 'I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman.' All the same, many writers from all cultures and periods of history were nominated - from Sappho (630 – 570 BCE) from the island of Lesbos to Murasaki Shikibu (c 973/978 – c 1014/1031), the Japanese author known for The Tale of Genji, considered by many to be the world's first novel.

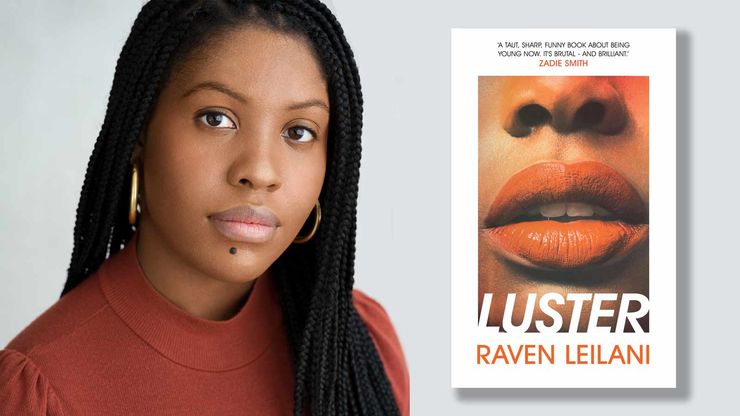

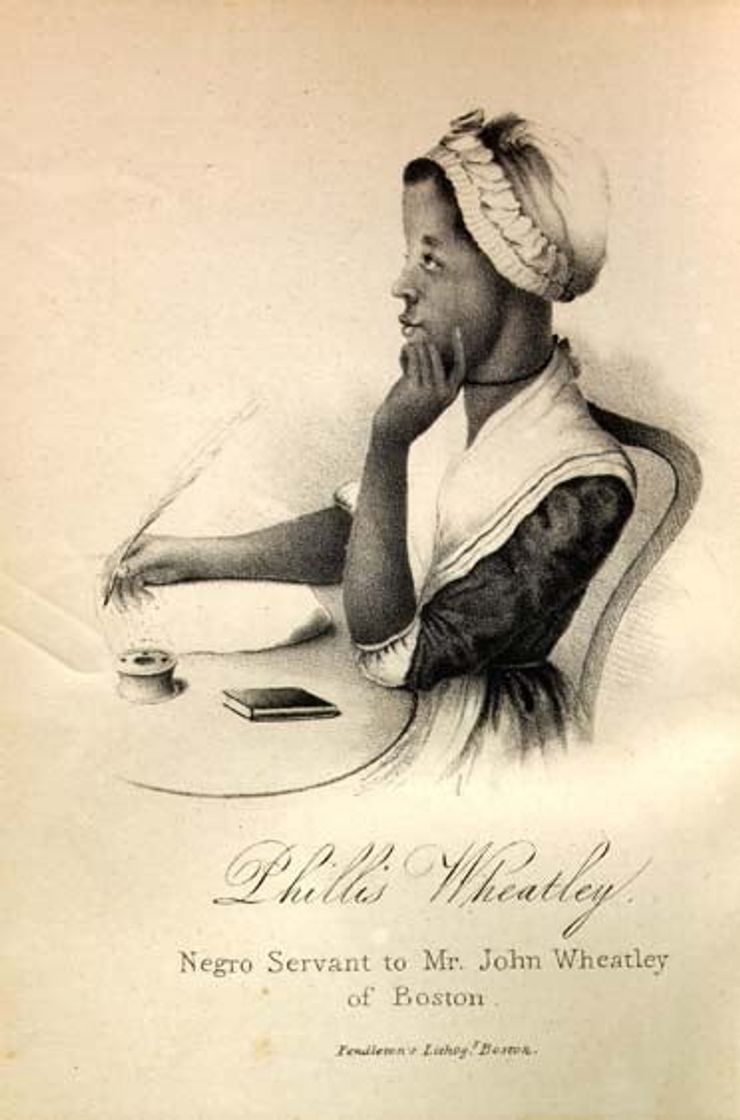

Aphra Benn, the 17th-century spy and playwright – the first professional female writer in England to make a living from her pen – was a popular nominee, as was Phillis Wheatley, an enslaved woman from West Africa who became the first published African-American poet in the 18th century. Zaynab Fawwāz (1860?–1914) is the first woman to publish a novel in Arabic and author of the first play by a woman in Arabic. Rachel Luzzatto Morpurgo (1790 – 1871) is said to be the first Jewish woman to write poetry in Hebrew under her own name in two thousand years and many people, including novelist Elif Shafak and Richard Osman, nominated the inspirational Iranian poet and filmmaker Forough Farrokhzad. Ding Ling (1904 – 1986) is one of the most celebrated of Chinese authors.

The power of women being free to write and publish cannot be underestimated. But for all those whose reputations have endured and whose work remains available, there are many thousands of others whose names have been forgotten. In Belfast’s Writer’s Square, an open space of grey stone and sharp angles, quotations from twenty-seven of Northern Ireland’s most celebrated authors are etched upon the ground. But how many of those passing through know that one of Ulster’s most important authors, Helen Waddell – a novelist, classical scholar, academic, translator, publisher and poet- is also commemorated here alongside the more familiar names of Seamus Heaney and C S Lewis? A literary celebrity in the 1920 and 1930s, Waddell was one of the most successful, most honoured writers of the inter-War years. Several highly-acclaimed works of scholarship, her dazzling novel Peter Abelard – first published in 1933 – was an instant critical success and huge bestseller. Yet today, Waddell’s books are out of print.

Women of Conviction

In our nominations, there’s no shortage of women whose achievements were misattributed or who were not given credit for their contribution. Think of Susan Hyde (1607 - 1656), a Royalist spy during the interregnum. Arrested and imprisoned, she died after two weeks of torture and abuse, but when her brother, the spymaster Sir Edward Hyde (later, 1st Earl of Clarendon) wrote a history of the rebellion, he didn’t even mention her name. Or the Austrian-Swedish physicist, Lise Meitner, who discovered the radioactive isotope protactinium-231 in 1917, but had to watch as the German chemist Otto Hahn was awarded the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1944 for their joint discovery of nuclear fission.

What’s also striking is how quickly the achievements of even those celebrated in their day as ground-breakers can be forgotten. Nominated by novelist Bernardine Evaristo, among many others, Mary Seacole was a healer, businesswoman and nursing pioneer who set up the ‘British Hotel’ behind the lines during the Crimean War. She was so famous in her day that a four-day fundraising Gala took place on the banks of the Thames for her in 1857, the same year her autobiography, Wonderful Adventures of Mrs Seacole in Many Lands, became a huge bestseller. Yet after her death in 1881, she largely vanished from the record for almost a century and was only brought back to prominence by the tireless efforts of campaigners.

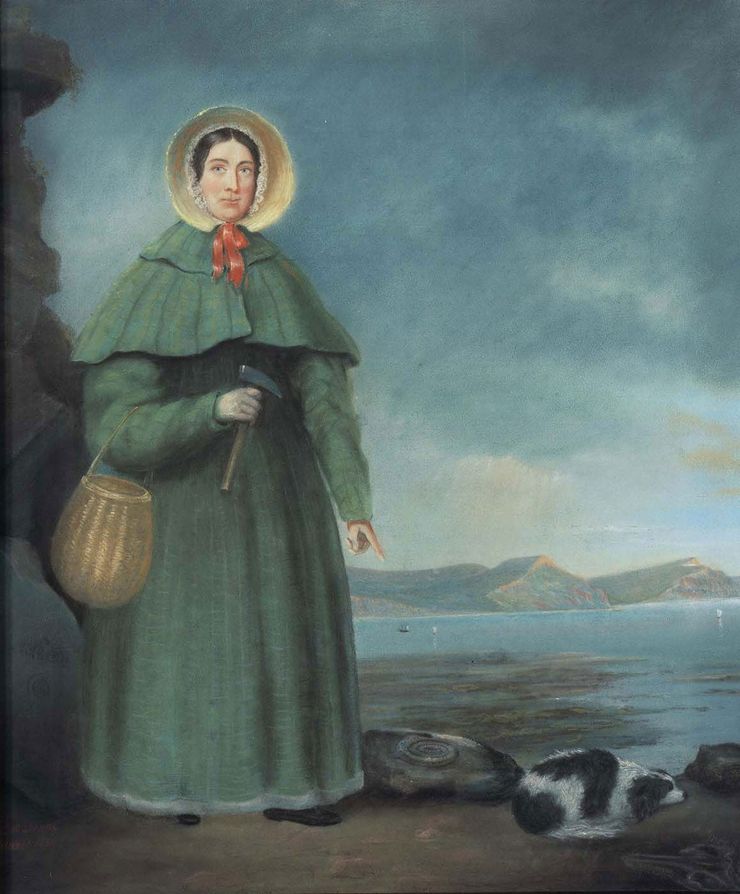

The same is true for the Victorian palaeontologist and fossil hunter campaign, Mary Anning. Born in Lyme Regis in 1799, she endured her work being overlooked and misattributed to the male collectors to whom she sold. Now, after years of campaigning, her reputation is secured. Thanks to the work of many, not least of all ‘Mary Anning Rocks’ – set up by a local girl, Evie Swire - a statue by Denise Dutton has been commissioned for Lyme Regis. And at the end of February 2021, it was announced that Anning’s life would be celebrated by the Royal Mint with a commemorative fifty-pence coin. It’s a similar story for Elizabeth Peratrovich (1911 – 1958), a civil rights activist, Grand President of the Alaska Native Sisterhood and member of the Tlingit nation. Instrumental in the passing of Alaska’s anti-discrimination act of 1945, the first such state law in the US, an ‘Elizabeth Peratrovich Day’ was established in Alaska in 1988 and, in 2020, a Native American $1 coin bearing her image was minted.

But for every Seacole or Anning or Peratrovich, there are many, many more throughout history whose inventions, writings, contributions deserve to be far more widely celebrated outside their immediate communities: think of the Kenyan social, environmental and political activist, Wangari Maathai (1940 – 2011), the first African woman to win a Nobel Prize; Emily Williamson (1885 – 1936), the founder (with Eliza Phillips) of the RSPB from her home in Manchester; the Belfast-born businesswoman, radical humanitarian and social reformer, Mary Ann McCracken (1770 – 1866) who was still protesting and handing out leaflets well into her eighties to keep slave ships out of Belfast Harbour; Rachel Carson, the 20th-century marine biologist, author and conservationist. Her book Silent Spring is considered one of the key texts in the environmental movement and, although its publication in 1962 was met with fierce opposition from chemical companies, it helped lead to a nationwide ban on DDT and other pesticides. Brilliant women all.

Together We Stand

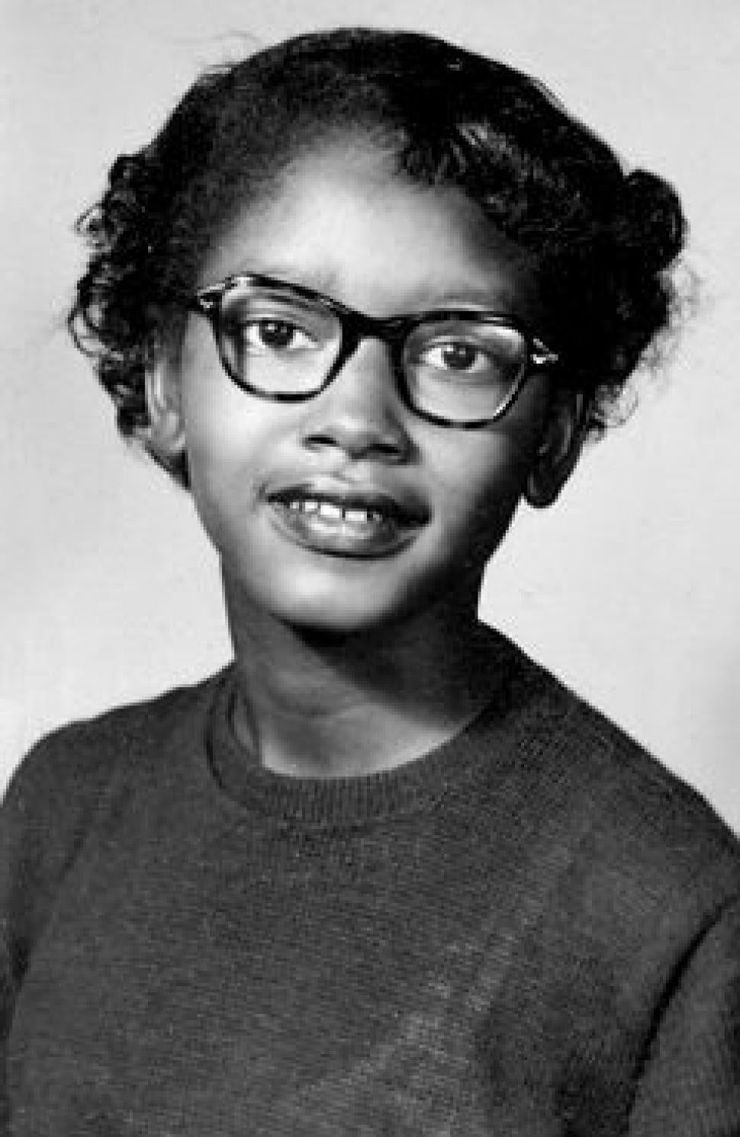

There was a strong sense, from many of the nominations, of how important it was to acknowledge all the women within a particular movement or campaign not just single out one or two: within the civil rights movement, the anti-abolitionist movement, suffrage and socialist feminist movements. Claudette Colvin was arrested at the age of 15 in Montgomery, Alabama in 1955 for failing to give up her seat on a bus, nine months before Rosa Parks.

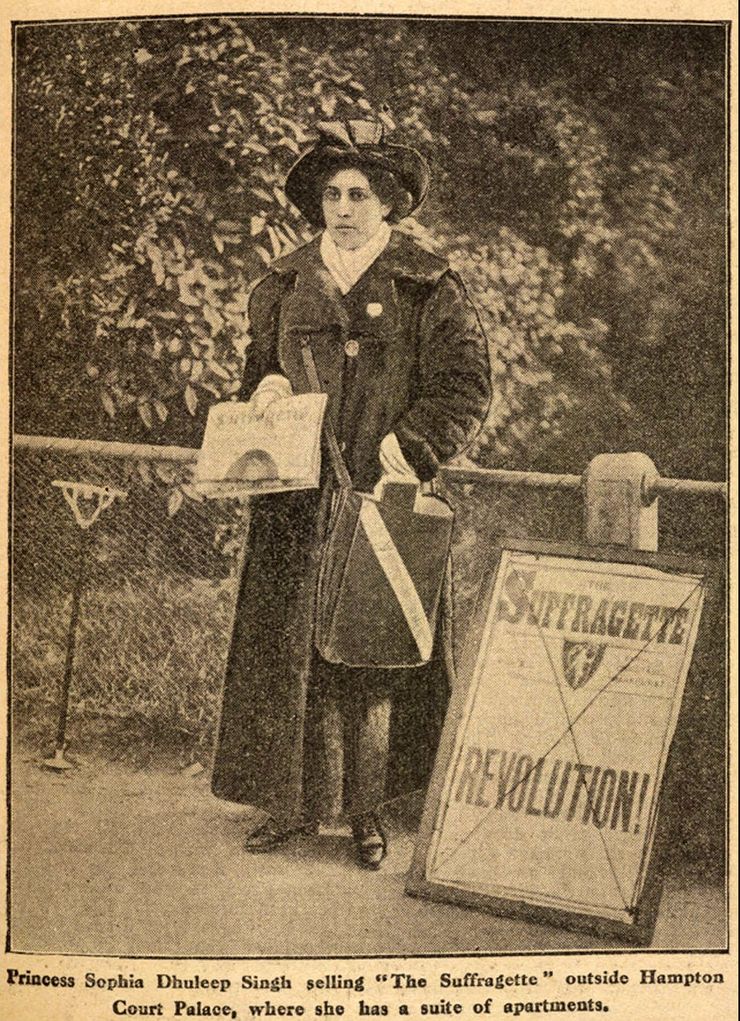

Alongside Millicent Fawcett and the Pankhursts, many wanted to honour those who are given well attention, particularly working-class activists and women of colour: from Rosa May Billinghurst (1875 – 1953), a polio sufferer who campaigned on a tricycle; Oldham’s Annie Kenny who, with Minnie Baldock, co-founded the first London branch of the Women’s Social and Political Union; Mary Gawthorpe (1881 – 1973), Sophia Duleep Singh; and Rosina Sky from Southend, who was head of the local Tax Resistance League. Their immense courage and stamina – mirrored in other universal suffrage and civil rights movements around the world – was the common factor in why so many people nominated these incredible women.

There was a similar spirit of wanting to acknowledge all the women who resisted during World War II, from every nation, as part of the SOE or official resistance networks, or simply women of principle who did what they could to help those around them. Senedu Gebru (1916 – 2019), educator, writer, leader of the Ethiopian Red Cross and the first woman elected to the Ethiopian Parliament, was part of the resistance to the Italian Occupation; Corrie ten Boom (1892 – 1983) was a watchmaker and member of the Dutch Reformed Church, who protected many Jewish families escape from the Nazis by hiding them in her home in Amsterdam; Noor Inayat Khan (1914 – 1944) was the first female radio operator sent into Nazi-occupied France by the SOE. Betrayed and captured by the Gestapo in 1943, she was transferred to Dachau and executed in 1944; Sophie Scholl was a young political activist and member of the White Rose non-violent resistance group in Nazi Germany. Convicted of high treason after having been found distributing anti-war leaflets at the University of Munich, she was executed by guillotine in 1943.

Endnote

This is only the beginning. There are so many extraordinary women, from all over the world to celebrate: adventurers and engineers, pilots and scientists - Ada Lovelace, Beatrice ‘Tilly’ Shilling, Hedy Lamarr, Rosalind Franklin, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Annie Jump Canon, Katherine Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan, Mary Jackson, Rita Levi Montalcini. Women of faith and women of reflection, women of activism and women of philanthropy. Our Living Legends list of nominations grows longer by the day, including Leah Namugerwa, the youth climate activist in Northern Uganda, the youth indigenous Brazilian climate activist Artemisa Xakriabá working to protect the Amazon rain forest, the Saudi women’s rights activist Loujain al-Hathloul and Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, UN Under-Secretary-General and Executive Director of UN Women. There are female heads of states in all corners of the world from Trinidad and Tobago, Serbia, Finland, Iceland and Germany to Nepal, New Zealand, Bangladesh, Slovakia and Barbados … and that list keeps growing too.

There were plenty of surprises. Novelist Irenosen Okojie nominated Ellen E Armstrong (1914 – 1979), the first black woman magician, illusionist and cartoonist in the US; Clare Balding chose the early 20th-century superstar footballer Lily Parr; Martina Navratilova, herself nominated several times, chose actress Katharine Hepburn. Did you know that the first patent for a dishwasher was given to Josephine Cochrane in 1886? That Miriam Kate Williams – known by her stage name Vulcana – was a Welsh strongwoman who toured music halls in Britain, Europe and Australia in the early part of the 20th century?

That Julie d’Aubigny (1670/73 – 1707) – known as Mademoiselle Maupin or La Maupin - was a cross-dressing, gender fluid duellist, adventurer and opera singer, who once set a nunnery on fire so she could rescue her girlfriend? Or that Marsha P Johnson (1945 – 1992), the African-American drag queen and activist who, with her friend Sylvia Rivera, founded the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries in 1970 was sometimes known as the ‘Saint of Christopher Street’?

Our �‘First 500’ is varied and fabulous, it sings with admiration for so many inspiring women throughout the ages and those who are making history today. It’s all about putting all the women back into history, not just a select few. Because only by learning about the whole past, in all its technicolour glory, can we really know where we stand now.

To end where we began, with Adrienne Rich:

‘‘The words are purposes/The words are maps.’’

— Adrienne Rich

Download a list of the first 500 remarkable women nominated in the #WomanInHistory campaign, below.

#WomanInHistory nominations - ‘First 500’

Here, Kate shares more about the importance of writing women back into history.