The best novels set in World War Two

Our selection of some of the best historical fiction books set during the Second World War.

With millions of lives lost, millions more displaced and the lines of countries changed and redrawn, World War Two changed the world in more ways than we can measure. Eight decades on from the end of the war, and in a world unrecognisable from the one at the heart of the conflict, authors continue to be fascinated by the lives of those on the frontline, and holding the fort back at home.

From heartwarming love stories, to tragic tales of betrayal and dark political comedies, read on for our picks of the best World War Two novels.

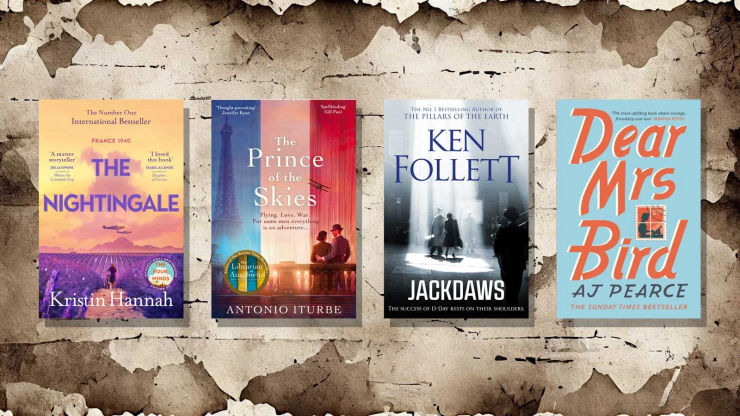

The Nightingale

by Kristin Hannah

A tale of resilience and endurance, and the unfettered strength of women during WW2, The Nightingale is the story of Vianne and Isabelle Mauriac, two sisters who are forging their own path and writing their own story in war-torn, Nazi-occupied France. Despite choosing different paths, Vianne living in the city and Isabelle in the country, the pair have always been close. As the war progresses they find themselves needing each other more than they ever have before. Heartbreaking, full of love and utterly unputdownable, The Nightingale has sold millions of copies and is soon to be a major film.

The God of that Summer

by Ralf Rothmann

Germany, summer 1945. Years of bombing have ravaged the cities and left millions homeless, forced to seek refuge in the countryside. For 12-year-old Luisa and her mother, Billie, their displacement offers a chance for a new start on a dairy farm. However, new dangers await them, and Luisa soon discovers that escaping the horrors of war is not the only challenge she faces. In The God of that Summer, Ralf Rothmann crafts a devastating tale about humanity’s capacity for violence and a society grappling with the inevitability of defeat.

The Prince of the Skies

by Antonio Iturbe

Writer, romantic, pilot, hero. Anthoine de Saint Exupéry has one dream, and that's to be a pilot. Despite his aristocratic origins, nothing can keep Anthoine grounded with his determination to take to the skies. From the bestselling author of The Librarian of Auschwitz comes an incredible novel based on the real life of Anthoine de Saint Exupéry and his mysterious death. Together with friends Jean and Henri, Anthoine pioneered new mail routes across the globe and changed aviation forever. At the same time, Anthoine began work on The Little Prince, a children's story that would go on to reach millions of readers around the world – despite the looming shadow of the Second World War.

The Most Precious of Cargoes

by Jean-Claude Grumberg

Told with a fairytale-like lyricism, this is a moving fable of family and redemption set against the horrors of the Holocaust. Once upon a time, a poor woodcutter and his wife lived in a forest. Despite their poverty and the war raging around them, the wife prays that they will be blessed with a child. A Jewish man rides on a train with his wife and twin babies. When his wife no longer has enough milk to feed them both, in desperation he throws his daughter into the forest, hoping that she’ll be saved. When the woodcutter’s wife finds the baby she takes her home, though she knows this act of kindness may lead to her death. This moving tale is a testament to our capacity for kindness in even the darkest times.

The Bastard Factory

by Chris Kraus

In his historical epic The Bastard Factory, Chris Kraus chronicles twentieth-century Europe through the lives of Hubert and Konstantin Solm, brothers born in Riga in 1907. From their upbringing in revolutionary Russia to working for the Nazis during WWII and emerging as spies for the newly created West Germany, the brothers navigate a tumultuous world with the help of their adopted Jewish sister, Ev. As the old world they knew fades away and a new order emerges, the trio becomes entangled in an epic love triangle that threatens to destroy them all.

The Yellow Bird Sings

by Jennifer Rosner

In Poland, 1941, Róza and her five-year-old daughter, Shira, spend their days and nights hiding in a farmer's barn after escaping being rounded up with the other Jews in their town. Róza tells her daughter stories of a yellow bird, the only one who can sing the melodies Shira composes in her head. Róza would do anything to keep her daughter safe, but eventualy she is faced with an impossible choice – keep her close, or let her go and give her a chance to survive.

The Fifth Column

by Andrew Gross

On his release from prison following a deadly confrontation with a Nazi sympathiser, all Charles Mossman wants to do is make amends with his wife and daughter. But, as support for America to enter the war of the side of the Allied Forces grows, the Nazi sympathisers are driven underground and Charles realises there are sinister forces surrounding them that will bring about the downfall of his nation by any means.

Jackdaws

by Ken Follett

Ken Follett is a master of epic historical fiction, and Jackdaws, set during the Second World War, is his writing at its unputdownable best. Set in the heart of the French Resistance the weeks before the D-Day landings, it’s a story of spies, love and revenge, and of the lengths that people will go to stay alive. As the Allied forces attempt to neutralise a vital Nazi telephone exchange, little do they know that there is a German spy-hunter on a mission in their midst.

The Order of the Day

by Eric Vuillard

A daring political novel set in a Europe on the brink of the Second World War, The Order of the Day is an award-winning novel by French author and filmmaker Éric Vuillard. Vuillard offers a darkly comedic look at the key meetings that happened ahead of war being declared in Europe, between Adolf Hitler and Germany’s industrial titans, Neville Chamberlain and Winston Churchill, and more. From international diplomacy gone wrong, to hoodwinked politicians and corporate greed, The Order of the Day perfectly captures how the decisions made by a handful of men led to the greatest conflict the world had ever seen.

Dear Mrs Bird

by AJ Pearce

The year is 1941, London is at war, and to say wartime spirit is alive and kicking is a radical understatement. The story centres on Emmeline Lake, who – contrary to her desire to become a ‘Lady War Correspondent’ – unwittingly takes up a position at the Woman’s Friend magazine, answering heartfelt letters from women seeking advice. The book is saturated in positivity but manages to steer clear of saccharine: a warmer, jollier, more uplifting book you will struggle to find.

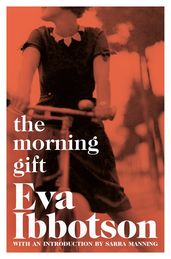

The Morning Gift

This classic WW2 romance is a story of unexpected love, independence and belonging from award-winning author Iva Ibottson. Eighteen-year-old Ruth loves her life in Vienna until the Nazis invade and her family is forced to flee. A terrible misunderstanding means she is left behind, and her only hope of escape is the marriage of convenience offered by Quinn, a young English professor who offers to bring her back to London.

The English Patient

by Michael Ondaatje

As the Second World War draws to a close, four disparate characters shelter in a house in an abandoned Italian village. Hana, a nurse, grieves for her father as she tends her last remaining patient, an anonymous Englishman burned beyond all recognition. Caravaggio, a spy and former thief, slowly extracts the story of the Englishman’s past from him, while a touching relationship develops between Hana and Kip, a Sikh bomb disposal expert. This is a heartbreaking love story and a beautiful novel about the traumas of war.

The Narrow Road to the Deep North

by Richard Flanagan

Winner of the Man Booker Prize 2014, The Narrow Road to the Deep North is the story of Dorrigo Evans, a surgeon living through the horrors of a Japanese POW camp on the Burma Death Railway. As he struggles to save the men under his command from starvation, beatings and cholera, he is haunted by an affair with his uncle’s wife years before.

The Kitchen Front

by Jennifer Ryan

With wartime morale low, and food supplies even lower, BBC Radio show The Kitchen Front launches a competition to find the most creative recipe using rations – with the prize of a lifetime! Dreaming of a life different from their day-to-day, young widow Audrey, her estranged sister Nell, and ambitious, London-trained chef Zelda all set their hearts on winning and becoming the programme’s first female presenter. Who will come out on top? This heartwarming, cosy novel about the lives of those on the home front was inspired by a true story from the Second World War.

To Die in Spring

by Ralf Rothmann

As the Second World War enters its final months, friends and coworkers Walter Urban and Friedrich 'Fiete' Caroli believe they are safe from the war’s atrocities, preferring to keep a low profile on the dairy farm where they work. However, with German resources scarce, they are forced to join the SS and experience the horrors of the frontline firsthand. Walter, recruited as a driver for a supply unit, is spared from the worst, but Fiete, sent to the front, is driven to desertion. Sentenced to death for his crime, Fiete and Walter find themselves reunited amid the tragedy of the conflict's final days.

A Jewish Girl in Paris

by Melanie Levensohn

When Judith, a young Jewish woman, embarks on a forbidden love affair with the son of a wealthy banker and Nazi sympathizer, she knows their romance can’t last. They devise a plan to escape together until Judith vanishes before they can flee. Decades later, in Montréal, a man confesses to his daughter on his deathbed that she has an older sister, Judith, who disappeared in 1940. As the family searches for Judith, they uncover a secret that threatens to tear them apart. Inspired by a true story, A Jewish Girl in Paris is an epic historical novel about forbidden love and hidden secrets.