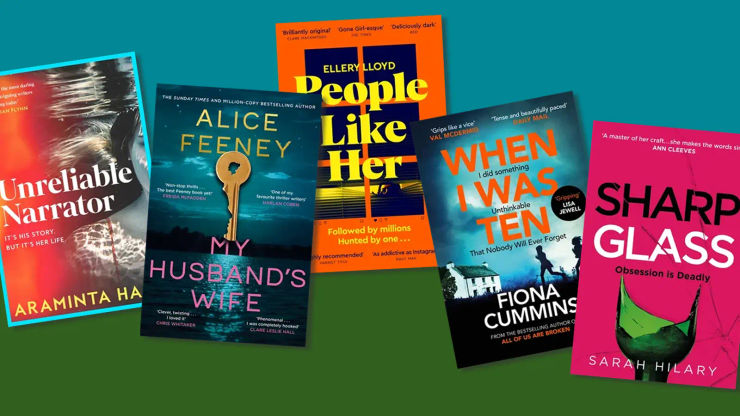

The best psychological thriller books you won't be able to get out of your head

You may not know who to trust while you're reading them, but you can definitely have confidence in our choice of the best psychological thriller books, as they're backed by the experts in the genre.

What is it about psychological thriller books that has us so gripped? Is it that, in contrast to an action thriller, or detective novel, they put us right at the heart of a story that feels like it could happen to us? Or because the suspense is rooted in the mental or emotional state of the characters, and our own uncertainty about them: their honesty, perception and motives? Perhaps it's that narrators in psychological thrillers are often unreliable, or compromised, and while we root for the protagonist, we are never 100 percent sure we can trust them . . .

Whatever the reason, if you, like us, can't get enough of them, we have curated a selection of brilliant psychological thrillers complete with recommendations from those in the know: other crime and thriller writers.

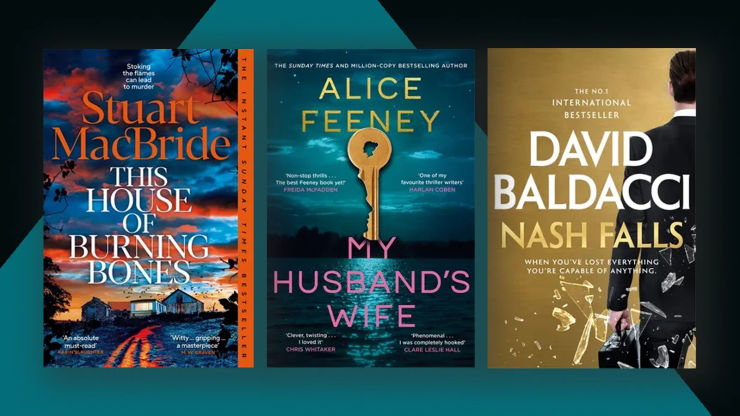

My Husband's Wife

by Alice Feeney

Why read this: The new thriller book from bestselling author Alice Feeney is a dark, clever read built around the ultimate domestic deception. Artist Eden Fox returns to her new home, Spyglass, from a run, to find her key doesn’t fit, and a woman who looks eerily like her answering the door. Worse, her husband insists this stranger is his wife. . .

If you’re looking for: Marriage thriller, coastal setting, doppelgängers, obsession, dual timelines.

Great for fans of: None of this is True by Lisa Jewell, The Guilty Couple by C.L. Taylor, The Wrong Sister by Claire Douglas.

What the experts say: ‘My Husband’s Wife is propulsive, compulsive, addictive and everything else you could possibly want a psychological thriller to be. I read it in under a day, breathlessly, with wide eyes’ – Lisa Jewell. ‘The best Feeney book yet!’ – Freida McFadden, author of The Housemaid.

Unreliable Narrator

by Araminta Hall

Why read this: This razor-sharp, creepy thriller will leave you constantly questioning what is real, as a woman discovers her life has been depicted in the pages of a bestselling novel. Ten years ago, ambitious and driven Hope landed a job with bohemian author Ambrose Glencourt, which ended in a fatal disaster. Hope has worked hard to keep the secret of those events ever since. But now, Ambrose has written a novel based on the story which paints a rather different version of events from what Hope remembers. Which one of them is the reliable narrator? This new novel from Araminta Hall is sure to be huge in 2026.

If you’re looking for: Books about books, feminist thriller, dark secrets, toxic relationships, revenge.

Great for fans of: Alice Feeney, Lisa Jewell.

What the experts say: 'Clever, sharp, and simmers with a perfectly contained rage' – Sarah Vaughan, author of Anatomy of a Scandal. ‘One of the most daring and intriguing writers working today’ – Gillian Flynn, author of Gone Girl.

People Like Her

by Ellery Lloyd

Why read this: A delightfully sinister and cleverly topical thriller, People Like Her is perfect for readers who love domestic suspense with a focus on modern life's darker side. Emmy Jackson is Instagram sensation Mamabare, famous for her unvarnished truth about parenthood. But Emmy isn't as honest as her followers believe, and someone out there knows her secret. And this person plans to make her pay. This page-turning debut explores the dangerous line between public honesty and private lies.

If you’re looking for: The dark side of social, influencer culture, modern parenthood.

Great for fans of: Liane Moriarty, Lucy Foley.

What the experts say: 'Breathlessly fast, brilliantly original' Clare Mackintosh, author of If I Let You Go and After the End.

Girl Falling

by Hayley Scrivenor

Why read this: This gripping mystery set in Australia's Blue Mountains has a vivid sense of place, a fractured friendship, and may or may not be a crime novel. . . The story follows Finn and Daphne, whose uneasy bond is tested when Finn's new girlfriend, Magdu, falls to her death during a rock-climbing trip. Was it an accident, or something more sinister?

If you’re looking for: Atmospheric setting, psychological mystery, friendship dynamics, dual perspective, Outback noir.

Great for fans of: The Valley by Chris Hammer, The Dry by Jane Harper, Chris Whitaker.

What the experts say: ‘Australian crime has a new star’ – Chris Hammer. 'An enthralling excavation of truth, with a vivid, human heart' – Benjamin Stevenson, author of Everyone in My Family Has Killed Someone.

The Girlfriend

by Michelle Frances

Why read this: Recently adapted into an Amazon Prime TV series, the original novel is one of our favourite psychological thrillers of all time, and more than worthy of a spot on your TBR if you missed it the first time around. Laura has it all. The career, a happy marriage, and a kind and handsome twenty-three year-old son, Daniel. Then Daniel meets Cherry, who hasn’t led Laura’s golden life . . . and she wants it. This chilling debut is the story of a mother, a son, his girlfriend and an unforgivable lie.

If you're looking for: Suspense, family dynamics, twisted relationships, secrets and lies.

Great for fans of: The Teacher by Frieda McFadden, Behind Closed Doors by B.A. Paris, The Lemon Grove by Helen Walsh.

What the experts think: ‘I was blown away. The Girlfriend is the most marvelous psychological thriller . . .I couldn’t put it down and kept sneaking upstairs to read another few pages . . . Please read this genuinely exciting novel.’ – Jilly Cooper, author of Rivals

When I was Ten

by Fiona Cummins

Why read this: An absorbing, tense, and utterly compelling thriller about a childhood crime and its devastating ongoing consequences. Twenty-one years ago, Dr Richard Carter and his wife were killed in a horrific double murder. Their ten-year-old daughter became known as the 'Angel of Death'. Now, a documentary team has tracked down her older sister, convincing her to speak for the first time. This explosive interview forces three women – including journalist and childhood friend of the sisters, Brinley Booth – to confront what really happened that night.

If you’re looking for: Secrets and guilt, journalist protagonist, compelling pace.

Great for fans of: Belinda Bauer, Erin Kelly, The Couple Next Door by Shari Lapena.

What the experts say: ‘Grips like a vice’ – Val McDermid. ‘Utterly compelling; a true just-one-more-chapter thriller’ – Clare Mackintosh, author of The Last Party.

The Sunshine Man

by Emma Stonex

Why read this: Following the success of The Lamplighters, Emma Stonex returns with a taut, emotionally charged thriller set in January 1989. Birdie has waited eighteen long years for this moment: the man who killed her sister is out of prison. With a gun in her bag and vengeance on her mind, she sets off for London. But as she closes in, secrets from the past begin to surface . . .

If you're looking for: 1980s thriller, historical crime, revenge plot, family secrets, emotionally charged, gripping, unreliable narrator, literary thriller.

Great for fans of: Emma Stonex’s The Lamplighters, Claire Fuller’s Unsettled Ground and Tana French’s The Hunter.

What the experts think: ‘A remarkable novel - heart-wrenching, unflinching and deeply compassionate . . . thrilling, and incredibly moving. If you loved The Lamplighters, I guarantee you’ll love The Sunshine Man too.’ ー Emylia Hall, author of The Shell House Detectives series.

Don't Miss

Nowhere to run: Emma Stonex on the power of claustrophobia in thrillers and the books that do it best

Read moreSharp Glass

by Sarah Hilary

Why read this: The latest novel from the Old Peculier Crime Novel of the Year winner and author of Black Thorn will trap you alone in a remote house in the country with a captor who has no intention of letting you go. . . A woman is held in a cellar, miles from anywhere. Her kidnapper believes she knows who murdered a young girl one year ago, and refuses to let her go until she reveals her secrets. But she is more of a match than they expect. . . Be prepared for an atmospheric battle of wills.

If you’re looking for: Captivity thriller, remote setting, intense psychological duel, murder mystery.

Great for fans of: Elly Griffith, Tana French.

What the experts say: ‘A master of her craft. In every book she makes the words sing’ – Ann Cleeves, author of the Vera and Shetland series. ‘Nail-biting, heart-wrenching stuff’ – Erin Kelly, author of The Skeleton Key.

A Nearly Normal Family

by M.T. Edvardsson (translated by Rachel Wilson-Broyles)

Why read this: A worldwide bestseller, this book asks the devastating question: how far would a parent go to protect their child when they are suspected of murder? When eighteen-year-old Stella is accused of killing someone, her parents, Adam and Ulrika, must confront how little they truly know about their daughter. Told from three viewpoints – father, mother, and daughter – this is a gripping, canny, and intensely suspenseful look at divided loyalties and the lies a family will tell.

If you’re looking for: Domestic suspense, family secrets, multiple perspectives, divided loyalties, legal thriller, moral ambiguity, unreliable narrator, explosive secrets.

Great for fans of: The Girl Before by J. P. Delaney, The Woman in the Window by A. J. Finn.

What the experts say: ‘A deceptive and riveting novel. A Nearly Normal Family will make you question everything you know about those closest to you’ – Karin Slaughter, author of Girl, Forgotten. ‘An utterly compelling premise with wonderful writing’ – Fiona Cummins, author of Into the Dark.