Rebecca Whitney on why women are drawn to domestic thrillers

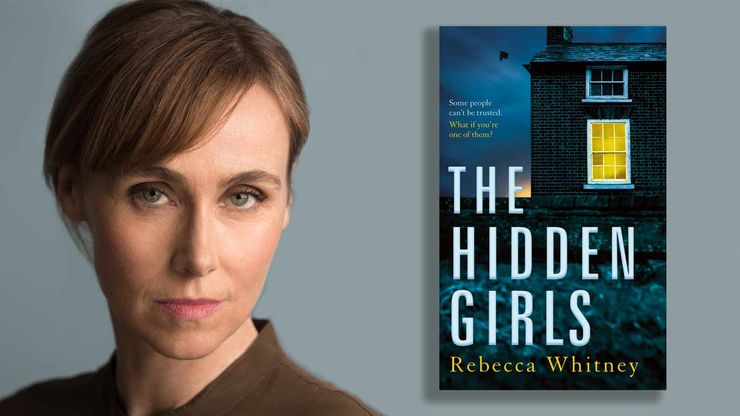

Rebecca Whitney, author of the psychological thrillers The Liar’s Chair and The Hidden Girls, discovers that women’s brains may be hardwired to love reading thrillers.

Crime and thriller is the most popular genre of book in the UK, and women, in particular, can’t get enough of these gripping reads. But why are women so drawn to the genre? Here Rebecca Whitney, author of the psychological thrillers The Liar’s Chair and The Hidden Girls, investigates.

With the phenomenal success of The Girl on the Train, which topped the UK and US bestseller lists, and Gone Girl becoming the 25th bestselling book of all time, it appears our thirst for thrillers goes unabated. Why do these page-turners have us in their grasp? Are we adrenalin junkies or do these stories satisfy a deeper need?

The majority of thriller fans are women, the edge-of-your-seat read tapping directly into the female psyche. But why? Part of the reason could be the mental gymnastics, making the book a more active experience. A thriller contains problems to be solved, a puzzle to be pieced together, and the excitement of anticipating the finale and whether or not we guessed the outcome ignites the detective in us and keeps us racing to the last page. It's an intense collaboration with the author, a direct wire into their brain, and the best thrillers continue to surprise us right to the end as the author leads us one way, then drops the unexpected from a great height.

Clinical psychologist Dr Sam Fraser cites neurological studies on male vs female brain function: ‘Men tend to process better in the left hemisphere of the brain while women tend to process equally well between the two hemispheres. This difference explains why men . . . approach problem-solving from a task-oriented perspective while women typically solve problems more creatively and are more aware of feelings while communicating. So men generally like it all laid out for them and women like to draw their own conclusions – i.e fill in the gaps of a plot perhaps?’

‘This genre . . . takes as its base a broadly feminist view that the domestic sphere is a challenging and sometimes dangerous prospect for its inhabitants.’

— Julia Crouch

Traditionally many thrillers have dealt with the explosive and the unfathomable, threats unlikely to affect the majority of their readership. While the market for these books is still healthy, another style of thriller is being read by women in abundance: the domestic noir. Author Julia Crouch, who coined the term in 2013 as a reaction to the limitations of the psychological thriller label, sums up this genre as taking place ‘primarily in homes and workplaces, concerns itself largely (but not exclusively) with the female experience, is based around relationships and takes as its base a broadly feminist view that the domestic sphere is a challenging and sometimes dangerous prospect for its inhabitants.’

The thriller in a domestic setting has a long-standing history with books such as Du Maurier's Rebecca and arguably even Brontë's Jane Eyre, fantastically reimagined in Jean Rhys' Wide Sargasso Sea. More recently, writers including Barbara Vine, Minette Walters, Sophie Hannah and Elizabeth Haynes have trail-blazed the flawed and complex female lead; it would seem that the success of Gone Girl merely highlighted this already well-established and much-loved sphere, prompting a proliferation of new titles as publishers rush to fill the gap that Flynn's novel has left in its wake.

Perhaps what's behind this female-led trend towards deep psychological domestic drama is the recognition in the stories of people just like us, in situations that are familiar. As women's lives become increasingly more full and complicated, perhaps the ability to take real risks is diminished. We live vicariously through the characters; it's the closest we come to inhabiting another's skin. As the mostly female protagonists make the mistakes we could so easily have made, we root for them to grapple through to the other side, or revel in their dysfunction as they get their just deserts. We experience the crash without being in the car. Fraser quotes more research: ‘Men have a more difficult time understanding emotions that are not explicitly verbalised, while women tend to intuit emotions and emotional cues. So could it be that women are more emotionally attuned and able to overlay their own emotions/fantasies etc. over a narrative whereas men are more concrete and less able to abstract when reading fiction?’

‘We no longer want to be the victim, and female-led thrillers give us back a quota of our power.’

The home is important: who we love and spend our days with – our primary relationships – are key to all our other relationships, and the dissection of the good and the bad we allow into our lives helps us to understand the greater world. Here is something we can hope to improve, and on some level control; we no longer want to be the victim, and female-led thrillers give us back a quota of our power. Crouch writes, ‘Women want to see ourselves in more active roles in stories. We're fed up with men coming in and sorting it all out.’

And a great book can offer us respite from a chaotic world. As we lose ourselves in the story, the realities of intangible and uncontrollable geopolitics temporarily fade. Some would argue it's easier to be swept away by a thriller than with other forms of literature, as the high-stakes impel us to discover what's always just over the next page. Our desire for justice demands we discover who triumphs and who gets their comeuppance and this delineation between good and evil is often more clear-cut than in other forms of fiction where questions can be left open-ended. Crouch writes: ‘Go to any crime writing festival and you will see many more women readers than men. My theory is that many women's lives are pretty full and chaotic, with work, caring responsibilities, 80% (still!) of the housework, etc. Crime fiction – particularly the more traditional police procedural/detective story – is all about order being restored to a temporarily disordered world. It is very satisfying like that.’

So is our addiction to thrillers a concern or can we bask in the satisfaction they bring us? Fraser writes: ‘Different personalities seek different forms of literature and therefore reading will serve various needs – enjoyment, relaxation, and stimulation. But escapism is great sometimes and an important healing factor.’

It would seem we should enjoy the ride.

Read on, I say.

The Hidden Girls

by Rebecca Whitney

Ruth is a new mother recovering from postpartum psychosis, and after months of hearing voices she’s no longer sure of her own judgement – and neither, it seems, is anyone else. When she hears a scream from a petrol station one night, she thinks it must be her mind playing tricks again, and the police and her husband agree. But what if there was a scream? Someone could be in trouble. They could need Ruth’s help . . .

The Liar's Chair

by Rebecca Whitney

Rachel Teller and her husband David appear happy, prosperous and fulfilled. The big house, the successful business . . . They have everything. However, when Rachel kills a man in a hit and run, the meticulously maintained veneer over their life begins to crack. Destroying all evidence of the accident, David insists they continue as normal. Rachel, though, is racked with guilt and as her behaviour becomes increasingly self-destructive she not only inflames David's darker side. Can Rachel confront her past and atone for her terrible crime? Not if her husband has anything to do with it . . .